Instruments : The Fiddle

The fiddle as we know it came from Italy at the end of the 17th century. In the time of Robert Burns (in 18th century Ayrshire) many areas of Scotland were still Gaelic speaking though it was becoming spoken less in the south of Scotland. Burns played the fiddle and was collecting tunes for his songs and many of the song tunes he collected were from the Gaelic tradition.

‘An Gille Dubh Mo Laochan’ - is an old Gaelic song but it is also popularly played on fiddle and other instruments. Burns used the tune for his song ‘A Man’s a Man for a’ that’.

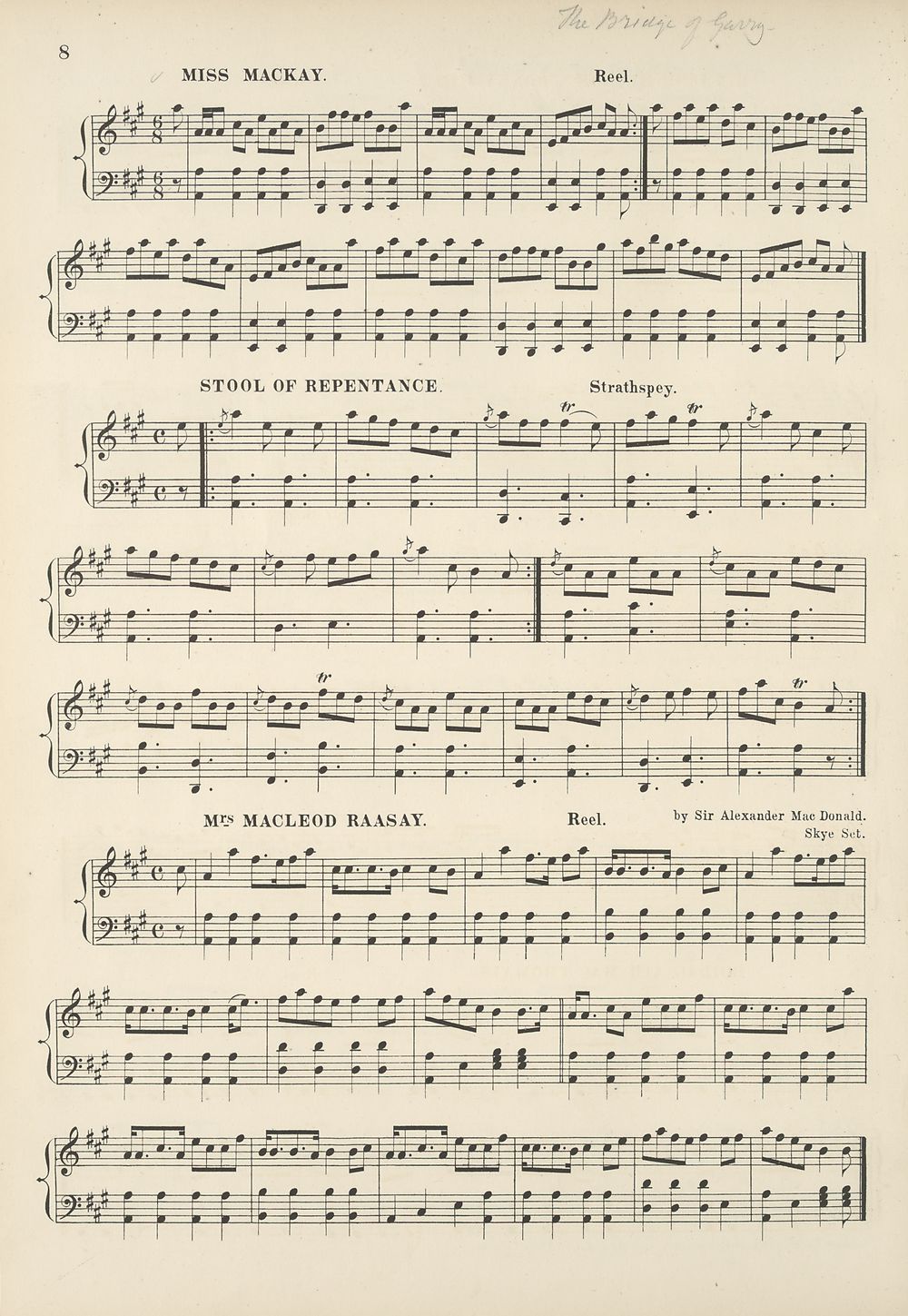

‘Mrs MacLeod of Raasay’ - is a reel published in Niel Gow’s (1727-1807) fifth collection in 1808 with this note ‘an original Isle of Skye Reel communicated by Mr Macleod.’ It was certainly being played when Dr Johnson and Boswell visited in 1773. It is now one of the most popular fiddle and pipe tunes in the world. The Gaelic songs ‘Mac -a - Phì’ and ‘Stad a Mhàiri Bhanarach’ use the first and second halves of this tune respectively. The tune is also used in the Scots song ‘Mac a Phee turn your cattle’ which has an interesting anglicisation of the Gaelic syllables.

Fiddle tunes used in popular songs

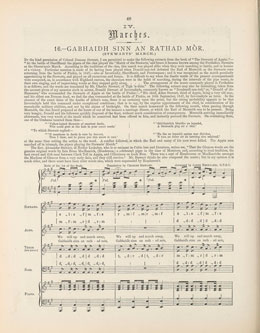

‘Gabhaidh Sinn an Rathad Mòr’ - this was reportedly played by the Stewart clan pipers at the battle of Sheriffmuir in 1715. It is a well-known and popular Gaelic children’s song. The tune is the same one that is also used for the Scots song ‘Katie Bairdie’ which is one of the oldest Scots songs for children and a popular fiddle tune. ‘Katie Bairdie’ is thought to date from the 17th century and is found in the manuscript of Sir William of Rowallan. Scholars believe he wrote it between 1612 and 1623. ‘Katie Bairdie’ only uses the first strain of the tune as we presently know it. Another tune which uses this melody is ‘Kafoozalum’. The pipe march ‘The High Road to Gairloch’ also uses this same tune. The latter two tunes have two parts which were probably added later as they are more contemporary compositions. The tune is also used for the English song ‘London Bridge is Falling Down’.

Puirt à beul and other songs

‘Brochan Lom’ - this is a puirt song for dancing (mouth music). Puirt meaning ‘tunes for a musical instrument’, and beul meaning ‘mouth’. More often performed now as a vocal solo without dance, puirt-a-beul mixes meaningless vocables and words with personal and topical references, and may involve complex rhythmic patterns that are just there to keep the beat going as good rhythm for the dancers. Often the tunes were sung for dancing if there were no instruments available.

‘High Road to Linton’ - it has been said that the first two parts of this tune are a port sung by the drovers on their way from the North Highlands to the market place at Perth. The last two parts are recent additions but now firmly established in the fiddle repertoire. The Gaelic song ‘Bodachan a’ Mhirein’ and the Scots song ‘Some say the Deil’s Dead’ are examples of lyrics being added to an old Gaelic fiddle tune.

‘Far am Bi mi Fhìn’ - is a Gaelic song that is also a popular bagpipe and fiddle tune called ‘The Drunken Piper.’ In its various versions it can be played as a strathspey, a 2/4 march and a reel and the pipers have a four part 2/4 march version called ‘Highland Rory.’

The Drunken Piper

Gaelic airs

Sometimes Gaelic airs are played freely and in imitation of the songs from which they have been taken. When played on the fiddle often a repeat is introduced where none would be in the song - this is more in keeping with the fiddle tradition of repeated parts. Many lovely Gaelic songs have fiddle versions that have been developed to suit and show off the fiddle skills and instrument range rather than being restricted to the original song note range. In some cases the Gaelic airs have been developed and arranged to become known as fiddle or pipe solos in their own right. A good example of this is ‘Màiri Bhàn Òg.’

Strathspeys

The Strathspey is one of the most recognisable features of Scottish music and song. Many academics have suggested that the Scots Snap (a very short accented note played on the beat before a longer note) as a musical pattern originates from the inflections of the Gaelic language and Gaelic singing.

‘Gun do dhiùlt am bodach fodar dhomh’ - is a Gaelic strathspey song but is also popularly played as a fiddle strathspey ‘Munlochy Bridge.’

Fiddle Pibrochs

It has been said that the repertoire of the harp (which was in existence before the Italian fiddle came to Scotland) was a great influence on the fiddle and bagpipe music of Scotland and in particular the pibroch repertoire. The distinctive Ceòl Mòr (big music) for fiddle introduced double stopping, different bowing patterns, scordatura tuning, ornamentation and a melody with variations. At this time bagpipe pibroch was also developing but it is thought that they both developed separately from the harp music of the time.

Around 17 fiddle pibrochs survive in 17th and 18th century manuscripts. Some of these have been transcribed from the wire strung harp repertoire. An example would be ‘Mackintosh’s Lament’ which appears as a fiddle pibroch in ‘The Patrick McDonald Collection’ 1784. This tune is in a scordatura tuning ie the fiddle is re-tuned to AEAE which gives a more drone type of sound where required.

The Pibroch of Dòmhnall Dùbh tune has been known for over 500 years. This fiddle tune is not really a pibroch in the true sense - basically a simple 6/8 march in bagpipe style – the Ceòl Beag (little music) version taken from the main theme of the pibroch of the same name. Dòmhnnall Dùbh refers to an incident which took place in the 15th century though we don’t know if the song was composed as early as that. The Dòmhnall Dùbh referred to in this song was ‘Black’ Donald Cameron of Lochiel. In 1411 Black Donald had fought on the side of the Lord of the Isles at the Battle of Harlaw but 20 years later led his clan to fight for the king against the MacDonalds and was defeated (though the chief himself survived). In actual fact, the song isn’t a summons to battle as the pipe-march title suggests but is actually a lament for the defeat and all those who died. Sir Walter Scott added to the confusion by writing a celebrated English version of the song, another incitement to battle, in 1816. In piping circles it is also known as ‘Locheil's’ March’ and ‘The Cameron's Gathering’.

By the late 18th century fiddle pibroch playing had declined. Notable recordings of some of these ancient fiddle pibrochs are those of Bonnie Rideout performing some of these pibrochs on ‘Scotland's Fiddle Piobaireachd’ Volumes 1 and 2, and the album ‘Harlaw’ which also contains some of these fascinating tunes - these albums are produced by well-known Scottish music expert Dr John Purser.

New pibrochs

In the 20th century the art of composing and playing new pibrochs has been revived by several talented exponents. Amongst players who have developed and revived fiddle pibroch music by writing new music in the style are Paul Anderson (Aberdeen), the late Ian Hardie (Nairn), the cellist David Johnson (Isle of Lewis), and Scott Skinner with his famous tune ‘Dargai’.

We should not overlook the great debt we owe to many Gaelic speaking musicians and tune collectors from the past and these give us a great insight into what was being played in the late 17th and early 18th century. Some of these tunes were old when they were collected. Many collectors were also composers and often added in their own compositions to their printed collections, or gave old tunes new titles, so sometimes it is difficult to know if a tune was a reworking of an old tune, a new composition or genuinely old.

Collections made by Patrick McDonald, Simon Fraser, Angus Fraser (the father of the better known Simon Fraser) Daniel Dow, John Bowie, Robb Donn and the interesting Gaelic bagpipe collection of William Gunn are very useful resources of Gaelic tunes. The English translations can be a little strange sometimes but they gave us the original Gaelic titles of many tunes that otherwise would perhaps now have been forgotten. Many of these aforementioned collectors lived in what is now the Gàidhealtachd - the Highland heart of Gaelic music and are a truly valuable resource for those wanting to further their knowledge of Gaelic music.

Further reading and useful links

- Christine Martin, ‘Traditional Scottish Fiddling’. Isle of Skye, Taigh na Teud, c2002. Shelfmark Mus.Box.q.43.32; Mus.38.39L

- Christine Martin, Susie Petrov and Dougie Pinnock (arr.). We're A' Connected : 95 Traditional Scottish songs alongside their dance tune arrangements for fiddle & pipes. Isle of Skye: Taigh na Teud, c2005.

- E-book reprints of valuable early tune books on The Best of Scotland’s music

- E-book reprints of valuable early tune books on The Best of Scotland’s music

- William Gunn bound collection from The Piping Centre shop