Historical sources

Gaelic and Scottish music in general is different from other countries’ folk music in that the border between folk and ‘classical’ art music is not as clear cut. Classical ‘art’ music is composed and passed on through various written notation methods. Folk music is usually passed on orally rather than being written down. However, Scottish traditional musicians embraced both oral and written methods in order to bring the music to audiences outside the traditional music communities.

Music for all the people

‘Classical’ musicians also embraced traditional music. Scottish traditional music featured at the Scottish royal court from the earliest times and remained of interest to wider parts of society rather than just appealing to traditional grassroots audiences.

This was a different development from the traditional repertories (or musical outputs) of, say, Irish music much of which was not written down until much later compared to Scottish traditional music. Before John and William Neal’s ‘Collection of the Most Celebrated Irish Tunes’ of 1724 Irish music appeared in Scottish and English music manuscripts and music publications for example the ‘Margaret Sinkler’s Manuscript Book’ of 1710 .

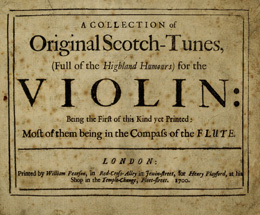

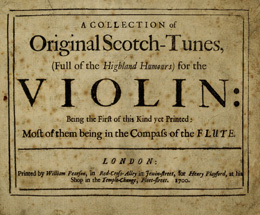

The first publication containing solely Scottish music was published in London as late as 1700. This was Henry Playford’s ‘Collection of Original Scotch Tunes’ (Library shelfmark: Ing.4) but Scottish music had been published much earlier, usually together with English and Welsh music.

Scottish music takes off

Airs and melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland

In the 18th century Scottish music publications increased in popularity and number. While there are early repertories of Gaelic music that have been lost completely and there is music that has gone out of fashion these can be re-discovered though surviving sources. Scottish music manuscripts and music publications have helped to keep these traditional repertories alive encouraging research and inspiring performances to this day.

Today, traditional musicians, while learning by ear and performing without written music are becoming increasingly interested in finding out more about early sources in order to learn about early performance practice, that is how the music was performed in the past.

Field recordings and historical commercial recordings are sources that capture the actual performance but it’s important to remember that the tradition passed down orally is done so through several generations and in doing so has likely changed the original.

Passing it on: orally

Airs and melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland

Traditionally folk music is passed down orally through families and communities who pass the repertory on through teaching and learning by ear.

Usually the tunes or songs are split into small sections that are first performed by the musician doing the teaching usually at a slow pace with the learner repeating the section. The sections are then put together and repeated until the learner feels more confident recalling the tune by him or herself. This is still the main method of teaching today.

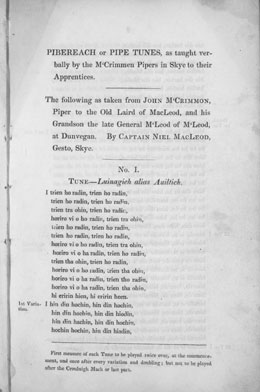

Bagpipe instruction includes the use of canntaireachd, the use of syllables for notes and rhythms, a similar system to that which is sometimes used for teaching song or even fiddle. The syllables of canntaireachd are sung but can also be written down which makes canntaireachd both an oral and written method of communicating the music. There are examples of canntaireachd in the Library’s music collections such as the famous collection of canntaireachd of Neil McLeod of Gesto.

A modern way of learning by ear

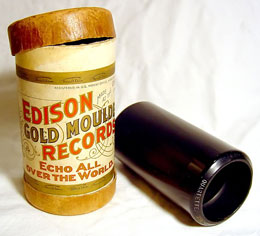

Recording performances became possible in the late 19th century. Wax cylinders and shellac records, that is records played at around 78 rpm (revolutions per minute), were the main recording formats that were established from the 1880s onwards.

The reel-to-reel tape became the main staple of recording format after World War II. It was a system that could easily be used professionally but also at home. It now became possible to record sessions in pubs as well as private music sessions at home. This allowed musicians to learn music not only directly from other musicians but also by listening to recordings. This is still the case today of course and is one of the reasons why Scottish music is so popular and has spread globally.

Changing formats

Recording formats have continued to evolve, for example, after the reel-to-reel tape, the cassette tape became the main recording format in the home. Vinyl records were replaced by CDs. As time moved on the world of sound recording became increasingly digital and the mp3 became a major delivery and recording tool.

Today, there are many different types of digital recording devices which allow an even higher quality of sound recording at home and while on the move. Professional sound recording has become easier and increasingly musicians are issuing and marketing sound recordings themselves. Today’s technology even allows the learner to slow down recordings without changing pitch. This makes it much easier to learn from recordings.

Passing it on: in writing (staff notation, canntaireachd, sol-fa notation)

Gaelic music was mainly passed down through the oral tradition. However, traditional musicians explored other ways to communicate their music in order to reach musicians in other communities. This could be done by noting down the music using a number of methods.

Canntaireachd

A special way of teaching music both orally and in writing was developed in the piping community using Canntaireachd. ‘The Oxford Dictionary of Music’ describes Cainntaireachd ‘as curious Scottish bagpipe notation, in which syllables stand for recognised groups of notes’. While Western style notation of Highland bagpipe music began to appear in the early 1800s, the music itself dates back much earlier and it is hardly surprising that a special system was invented to help memorising these often quite complicated tunes. Canntaireachd literally means humming a tune. It uses a system of vowels and consonants representing notes of the tune and its variations in such a way that it can be sung and used to teach bagpipe tunes.

Staff notation

Staff notation was the most accessible form of passing on the music to other musicians, especially classically trained musicians. Gaelic tunes, songs, bagpipe music and fiddle tunes were collected by both traditional and ‘classical’ musicians and published. This made the music accessible to those who could read Western staff notation.

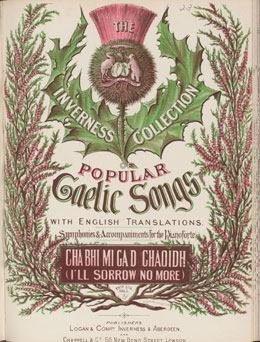

Initially Scottish songs found their way into published song collections amid English, Irish and Welsh songs, for example John Playford’s ‘Choice new songs’ (1684) or Henry Playford’s ‘Wit and mirth: or pills to purge melancholy (1699). In 1700 the first publication containing solely Scottish tunes was published by Henry Playford in London: A Collection of Original Scotch-Tunes, (Full of the Highland Humours) for the Violin: Being the First of this Kind yet Printed (1700) (Library shelfmark: Ing.4)

Important Scottish and Gaelic music publications include:

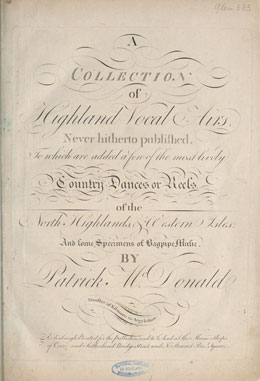

- Macdonald’s Collection of Highland Vocal Airs (1784).

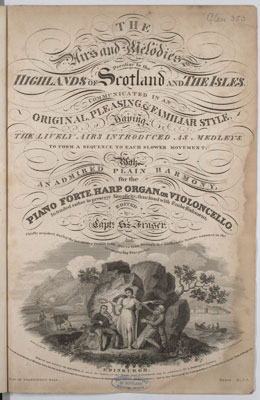

- Fraser’s ‘Airs and melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland’ (1816).

- Campbell’s ‘Albyn's anthology’ (1816).

- Macdonald’s ‘Ancient Martial Music of Caledonia called Pìobaireachd’ (1822).

- MacLeod of Gesto’s ‘Collection of piobaireachd’ (1828).

- Mackay’s ‘Collection of Ancient Piobaireachd or Highland Pipe Music’ (1838).

The subscribers’ list of Patrick Macdonald’s ‘Collection of Highland Vocal Airs’ (1784) contains people from many backgrounds who supported the publication in advance in order to help fund it. They include members of the aristocracy, clergy, teachers, military personnel, merchants, musicians, historians and music publishers. Geographically, there was also a wide spread with subscribers based in the Highlands and Islands, provincial English and Scottish towns and major cities such as London and Edinburgh.

Popular songs

In the 18th and 19th centuries Scottish songs became very popular in London, this was mainly Scots songs but also included songs that originated in the Gaelic tradition. For example, there is a connection between the fiddle version of the tune ‘Mrs MacLeod of Raasay’ and the Gaelic songs ‘Mac-a-Phee’ and ‘Stad a Mhàiri Bhanarach’.

Other popular songs were:

Limitations of Western staff notation

Scottish music printed in Western notation presented basic versions of the tunes or versions with ornamentation such as adding extra notes trying to convey the Scottish style. However, notation alone cannot precisely represent an authentic performance of the music with its characteristics in pitch and rhythm. Contemporary compilers of Highland music were aware of the limitations of presenting it in the form of Western staff notation:

‘Although many of the Luinigs are very pleasing, when sung by a Highlander with that animation and enthusiasm with which they never fail to inspire him, yet they may appear but trifling and insipid, perhaps, when played from notes by a person who never heard them sung, and who has no portion of that enthusiasm.’ (Patrick Macdonald, 1784)

The best way to learn traditional Scottish music is still through the oral method directly from a traditional musician or listening to recordings.

Airs and melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland

Tonic sol-fa notation

Airs and melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland

Airs and melodies peculiar to the Highlands of Scotland

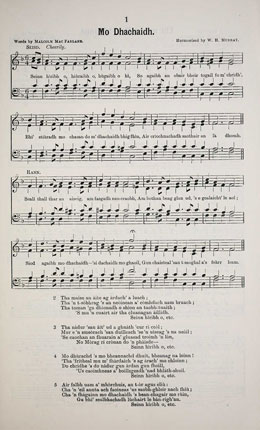

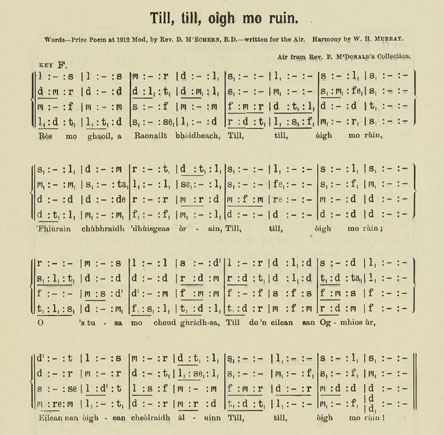

An interesting alternative notation method was developed in the 19th century using characters: the tonic sol-fa method. This method was invented by Sarah Anna Glover (1785-1867), a Norwich music teacher, and promoted widely by music publishers John Curwen and John Spencer Curwen from the middle of the 19th century onwards.

The system is based on the Guidonian solmization. This is a system which represents anglicized solfège syllables (e.g. do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti, do with individual letters (e.g. d, r, m, f, s, l, t, d). Rhythm is represented via a combination of spacing and punctuation marks.

Interestingly this method, which went out of fashion in the middle of the 20th century is still widely used in the context of Gaelic music, especially music set for Mod competitions. An Commun, the publisher of most Mod set pieces of music still publish the music in both notation systems.

Classical music adaptations

Many Scottish musicians as well as Scottish music publishers moved to and from England and European countries, particularly in the 18th and 19th centuries. In doing so they ensured Scottish music was made accessible to a wide range of audiences far beyond Scotland.

Scottish airs including Gaelic airs reached the London music market through music publications. Local musicians as well as visiting musicians from the continent, both professional and amateur, were able to access Scottish music through the purchase of music publications.

Publishers and composers of classical music became very interested in Scottish tunes. They re-worked them into classical compositions like rondos (a musical form using repeated themes) or variations often set for the pianoforte. Songs were particularly popular, though not all were using authentic material.

Inspired by Scottish culture

Some English and foreign composers were inspired by Scottish culture including Ossian (the legendary Gaelic bard) as well as the countryside to create music with a Scottish theme though often not ‘Scottish’ in a musical sense. For example: Mendelssohn’s ‘Fingal’s Cave’ overture and ‘Scottish symphony’ were inspired by his visit to Scotland but didn’t really contain Scottish music.

Max Bruch, the late 19th /early 20th century German Romantic composer used some Scottish material in some of his compositions although in a limited way. The 19th century French Romantic composer Hector Berlioz was inspired by Sir Walter Scott’s literature to give his overture ‘Waverley’ its name.

Technological advances

With the rise of technological advances in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, sound recordings became more widely available as another way for music to reach wider audiences. Scottish traditional music including Gaelic music was recorded onto wax cylinders and shellac records (‘78s’) which helped to make Scottish music accessible to those who couldn’t read music notation.

Gaelfonn

Murdo Ferguson set up a record label, Gaelfonn, specialising in Gaelic music and language courses. Listen to audio samples on the Digital Collections page.

Globalisation

Musicians have travelled extensively for many centuries, on tour or through emigration. The musical exchange that this widespread travel brought increased in the 18th century and reached new heights in the 19th century with the arrival of the modern railway.

With leisure travel now extended to the middle classes, the ‘grand tour of Europe’ included not only continental Europe but also the British Isles. It was in this era that tourism as a leisure activity was truly born and in the 20th century it finally reached wider section of the population.

In recent decades cheap travel has put access to music festivals within the reach of most people and it’s not surprising that Scottish music and in particular music created and performed in the Highlands and Islands draws in visitors from all over the globe.

Further reading

- Henry George Farmer. A history of music in Scotland. London: Hinrichsen, [1957]

- Francis Collinson. The traditional and national music of Scotland. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1966.

- Francis Collinson. The Bagpipe fiddle and harp. Newtongrange, Midlothian: Lang Syne Publishers, 1983.

- Francis Collinson. The Bagpipe. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1975.

- Roderick D Cannon. The Highland Bagpipe and its Music. Edinburgh: John Donald, 1988.

- Roderick D Cannon. A Bibliography of Bagpipe Music. Edinburgh: John Donald, 1980.

- Seonair. Gaelic Names of Pipe Tunes. Kingston, Ont., Canada: Iolaire, 1994.

- Allan Macdonald. The relationship between pibroch and Gaelic song: its implications on the performance style of the pibroch urlar. MLitt thesis. University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, 1995. (online at https://www.cl.cam.ac.uk/~rja14/musicfiles/manuscripts/allanmacdonald/)

- Anne Lorne Gillies. Songs of Gaelic Scotland. Edinburgh: Birlinn, 2005.

- George S Emerson. Rantin’ Pipe and Tremblin’ String. A history of Scottish dance music. London: J M Dent, 1971.

- Roger Fiske. Scotland in music. A European enthusiasm. Cambridge: CUP, 1983.

- John Purser. Scotland’s music: A history of the traditional and classical music of Scotland from early times to the present day. Edinburgh: Mainstream Publishing, 2007.

- Bill Dean-Myatt. A Scottish vernacular discography, 1888-1960. Hailsham: City of London Phonograph & Gramophone Society, 2013.

- Aloys Fleischmann, Mícheál Ó Súilleabháin and Paul McGettrick (eds.) Sources of Irish traditional music, c. 1600-1855. New York: Garland, 1998.