Instruments : The Clarsach

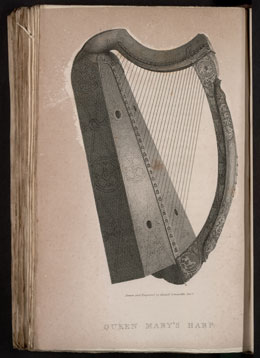

Clarsach is the Gaelic word for a harp, but harps come in many different varieties from all over the world. The harp used in Gaelic Scotland for centuries was a particular type, shared with Gaelic Ireland. Two famous old harps in the National Museum of Scotland are good examples of the old clarsach: the Queen Mary harp and the Lamont harp are small, sturdy instruments. Their soundboxes are carved from willow wood , and they used to have brass wire strings. The Queen Mary harp has been radiocarbon-dated to the 14th century , but we don’t yet know the age of the Lamont harp.

The old clarsachs were played in a learned oral tradition, by harpers trained in the bardic schools in Ireland as well as in Scotland. Their music was formal, elaborate, and probably related to the piobaireach of the bagpipes. This is an example of re-imagined medieval Gaelic harp music played on the replica of the Queen Mary clarsach.

The music that the harpers played for their patrons was not written down by the harpers, and only survives in later manuscripts and books, in settings for lute, fiddle, or other instruments.

The clarsach was also very important as an accompaniment to the singing or reciting of Gaelic poetry . Harpers travelled back and forth between Ireland and Scotland, working for kings, princes and clan chiefs in the Gaelic courts and big houses.

There must have been many more clarsachs like the two in the National Museum, but no others survive in Scotland. The clarsach stopped being played in Scotland during the 18th century. Gaelic harpers in Ireland continued through into the 19th century and some of them toured in Scotland.

Why did clarsach playing decline and disappear? No-one really knows. There must be many reasons – the rise of the pipes and fiddle, the decline of the old Gaelic aristocracy who would have supported and paid for the formal training of the harpers, the decline of learned Gaelic culture and the hereditary scholarly families, with the loss of manuscript collections and bardic schools, and changes in musical fashion as English and European styles came North.

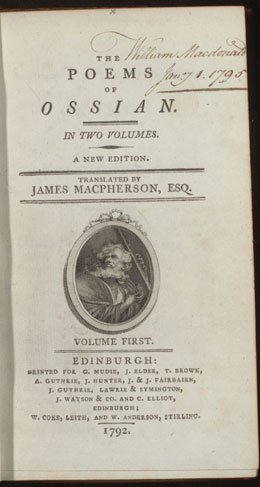

But the clarsach was becoming a potent cultural icon outside the Gaelic world, and harps appeared in Romantic literature even after they were no longer played. MacPherson’s Ossian is full of the harp as a vehicle for poetic inspiration.

When 19th century Scottish aristocrats wanted to build a Gaelic revival, they wanted the clarsach to have a place in it. But because the old Gaelic harp tradition had already disappeared, they didn’t have any easy way to get Gaelic harping up and running again. So they looked to England, and used harps from the Anglo-Continental harp traditions to bring the lost Gaelic harp traditions back to life. In the early 1800s, Margaret MacLean-Clephane played her transcriptions of Gaelic harp tunes and Gaelic song airs on a London made pedal harp.

The Mòd started in the 1890s, with a section each year for Gaelic singing with clarsach accompaniment. The harps used for the Mod from 1893 on were made in London by a pedal-harp maker. They were made small and decorated to look old and Gaelic even though their design and construction was completely in the Anglo-Continental tradition, with gut strings and chromatic mechanisms.

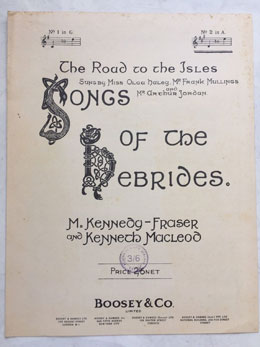

Throughout the 20th century, this new type of clarsach became firmly established in Scottish musical life. At first it was used just for song accompaniment, usually for the Gaelic songs collected and arranged by Marjory Kennedy-Fraser.

You can hear a recording of Patuffa Kennedy-Fraser recorded in 1929.

This is all sung in English which shows how strongly influenced the Gaelic revival was by Anglo cultural norms.

In the 1970s, Alison Kinnaird pioneered the use of this new gut-strung small harp to play instrumental music. She positioned the harp as a traditional instrument in Scottish music, aiming to let it take its place alongside pipes and fiddle. Today there are thriving traditions of clarsach playing in traditional, classical and jazz-fusion styles of Scottish music.

However, there was a kind of residual awareness that these new designs of harp, with gut strings (nowadays more commonly synthetic), and chromatic mechanisms, are not in the same tradition or lineage of making or playing, as the old Gaelic harps of previous centuries. From the 1890s, there have been “early music” style attempts to recreate the historical Gaelic style of clarsach, with metal wire strings. Good archaeological replicas of the museum harps were made by Edinburgh instrument-maker Glen in 1892 for the first Mòd, but these were too difficult for classically-trained harpists to play and so were abandoned by the next year in favour of the new Anglo-Continental gut-strung designs. Ever since then, there have been two strands of clarsach playing in Scotland – the mainstream of classical-influenced playing on chromatic gut-strung small harps, and the niche of historical recreation, using diatonic historical-style wire-strung reproductions to try and recreate historical style, technique and repertory.

Further reading

- Robert Bruce Armstrong, The Irish and Highland harps by David Douglas, Edinburgh, 1904

- Simon Chadwick, ‘The contest between instrument and idea: “the harp”’, The cultural history of musical instruments in Scotland, 1700-present day’. Birlinn, forthcoming

- Stuart Eydmann, ‘In good hands: the Clarsach Society and the renaissance of the Scottish harp’. The Clarsach Society, Edinburgh, 2017

- Karen Loomis, David Caldwell, Jim Tate, Ticca Ogilvie, & Edwin J. R. van Beek, ‘The Lamont and Queen Mary harps’ Galpin Society Journal XV, 2012

- Keith Sanger & Alison Kinnaird ‘Tree of strings - crann nan teud’, Kinmor Music, 1992

- Helene Witcher, ‘Madame Scotia, Madam Scrap’, Islands Book Trust, 2017