Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(579) Page 569

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

[ITALIAN.

SCULPTURE

569

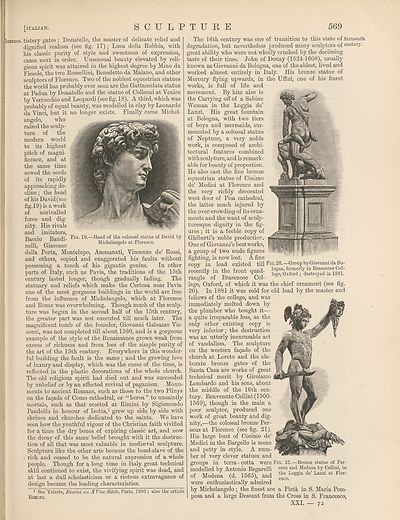

Fig. 19.—Head of the colossal statue of David by

Michelangelo at Florence,

Florence, tistery gates ; Donatello, the master of delicate relief and

dignified realism (see fig. 17); Luca della Robbia, with

his classic purity of style and sweetness of expression,

came next in order. Unsensual beauty elevated by reli¬

gious spirit was attained in the highest degree by Mino da

Fiesole, the two Rossellini, Benedetto da Maiano, and other

sculptors of Florence. Two of the noblest equestrian statues

the world has probably ever seen are the Gattamelata statue

at Padua by Donatello and the statue of Colleoni at Venice

by Verrocchio and Leopardi (see fig. 18). A third, which was

probably of equal beauty, was modelled in clay by Leonardo

da Vinci, but it no longer exists. Finally came Michel¬

angelo, who

raised the sculp¬

ture of the

modern world

to its highest

pitch of magni¬

ficence, and at

the same time

sowed the seeds

of its rapidly

approaching de¬

cline ; the head

of his David (see

fig. 19) is a work

of unrivalled

force and dig¬

nity. His rivals

and imitators,

Baccio Bandi-

nelli, Giacomo

della Porta, Montelupo, Ammanati, Vincenzo de’ Rossi,

and others, copied and exaggerated his faults without

possessing a touch of his gigantic genius. In other

parts of Italy, such as Pavia, the traditions of the 15th

century lasted longer, though gradually fading. The

statuary and reliefs which make the Certosa near Pavia

one of the most gorgeous buildings in the world are free

from the influence of Michelangelo, which at Florence

and Rome was overwhelming. Though much of the sculp¬

ture was begun in the second half of the 15th century,

the greater part was not executed till much later. The

magnificent tomb of the founder, Giovanni Galeazzo Vis¬

conti, was not completed till about 1560, and is a gorgeous

example of the style of the Renaissance grown weak from

excess of richness and from loss of the simple purity of

the art of the 15th century. Everywhere in this wonder¬

ful building the fault is the same; and the growing love

of luxury and display, which was the curse of the time, is

reflected in the plastic decorations of the whole church.

The old religious spirit had died out and was succeeded

by unbelief or by an affected revival of paganism. Monu¬

ments to ancient Romans, such as those to the two Plinys

on the fagade of Como cathedral, or “ heroa ” to unsaintly

mortals, such as that erected at Rimini by Sigismondo

Pandolfo in honour of Isotta,1 grew up side by side with

shrines and churches dedicated to the saints. We have

seen how the youthful vigour of the Christian faith vivified

for a time the dry bones of expiring classic art, and now

the decay of this same belief brought with it the destruc¬

tion of all that was most valuable in mediaeval sculpture.

Sculpture like the other arts became the bond-slave of the

rich and ceased to be the natural expression of a whole

people. Though for a long time in Italy great technical

skill continued to exist, the vivifying spirit was dead, and

at last a dull scholasticism or a riotous extravagance of

design became the leading characteristics.

1 See Yriarte, Rimini au XVme Siecle, Paris, 1880 ; also the article

Rimini.

The 16 th century was one of transition to this state of Sixteenth

degradation, but nevertheless produced many sculptors of century,

great ability who were not wholly crushed by the declining

taste of their time. John of Douay (1524-1608), usually

known as Giovanni da Bologna, one of the ablest, lived and

worked almost entirely in Italy. His bronze statue of

Mercury flying upwards, in the Uffizi, one of his finest

works, is full of life and

movement. By him also is

the Carrying off of a Sabine

Woman in the Loggia de’

Lanzi. His great fountain

at Bologna, with two tiers

of boys and mermaids, sur¬

mounted by a colossal statue

of Neptune, a very noble

work, is composed of archi¬

tectural features combined

with sculpture, and is remark¬

able for beauty of proportion.

He also cast the fine bronze

equestrian statue of Cosimo

de’ Medici at Florence and

the very richly decorated

west door of Pisa cathedral,

the latter much injured by

the over-crowding of its orna¬

ments and the want of sculp¬

turesque dignity in the fig¬

ures ; it is a feeble copy of

Ghiberti’s noble production.

One of Giovanni’s best works,

a group of two nude figures

fighting, is now lost. A fine

copy in lead existed till 20.—Group by Giovanni da Bo-

recently in the front quad-

rangle of Brasenose Cof-

lege, Oxford, of which it was the chief ornament (see fig.

20). In 1881 it was sold for old lead by the master and

fellows of the college, and was

immediately melted down by

the plumber who bought it—

a quite irreparable loss, as the

only other existing copy is

very inferior; the destruction

was an utterly inexcusable act

of vandalism. The sculpture

on the western fagade of the

church at Loreto and the ela¬

borate bronze gates of the

Santa Casa are works of great

technical merit by Girolamo

Lombardo and his sons, about

the middle of the 16th cen¬

tury. Benvenuto Cellini (1500-

1569), though in the main a

poor sculptor, produced one

work of great beauty and dig¬

nity,—the colossal bronze Per¬

seus at Florence (see fig. 21).

His large bust of Cosimo de’

Medici in the Bargello is mean

and petty in style. A num¬

ber of very clever statues and

groups in terra-cotta were Fig. 21.—Bronze statue of Per-

modelled by Antonio Begarelli seus and Medu,sa Cellini-in

of Modena (d. 1565), and t^LoggM de La™ »t Flor-

were enthusiastically admired

by Michelangelo; the finest are a Pi eta in S. Maria Pom-

posa and a large Descent from the Cross in S. Francesco,

XXL — 72

SCULPTURE

569

Fig. 19.—Head of the colossal statue of David by

Michelangelo at Florence,

Florence, tistery gates ; Donatello, the master of delicate relief and

dignified realism (see fig. 17); Luca della Robbia, with

his classic purity of style and sweetness of expression,

came next in order. Unsensual beauty elevated by reli¬

gious spirit was attained in the highest degree by Mino da

Fiesole, the two Rossellini, Benedetto da Maiano, and other

sculptors of Florence. Two of the noblest equestrian statues

the world has probably ever seen are the Gattamelata statue

at Padua by Donatello and the statue of Colleoni at Venice

by Verrocchio and Leopardi (see fig. 18). A third, which was

probably of equal beauty, was modelled in clay by Leonardo

da Vinci, but it no longer exists. Finally came Michel¬

angelo, who

raised the sculp¬

ture of the

modern world

to its highest

pitch of magni¬

ficence, and at

the same time

sowed the seeds

of its rapidly

approaching de¬

cline ; the head

of his David (see

fig. 19) is a work

of unrivalled

force and dig¬

nity. His rivals

and imitators,

Baccio Bandi-

nelli, Giacomo

della Porta, Montelupo, Ammanati, Vincenzo de’ Rossi,

and others, copied and exaggerated his faults without

possessing a touch of his gigantic genius. In other

parts of Italy, such as Pavia, the traditions of the 15th

century lasted longer, though gradually fading. The

statuary and reliefs which make the Certosa near Pavia

one of the most gorgeous buildings in the world are free

from the influence of Michelangelo, which at Florence

and Rome was overwhelming. Though much of the sculp¬

ture was begun in the second half of the 15th century,

the greater part was not executed till much later. The

magnificent tomb of the founder, Giovanni Galeazzo Vis¬

conti, was not completed till about 1560, and is a gorgeous

example of the style of the Renaissance grown weak from

excess of richness and from loss of the simple purity of

the art of the 15th century. Everywhere in this wonder¬

ful building the fault is the same; and the growing love

of luxury and display, which was the curse of the time, is

reflected in the plastic decorations of the whole church.

The old religious spirit had died out and was succeeded

by unbelief or by an affected revival of paganism. Monu¬

ments to ancient Romans, such as those to the two Plinys

on the fagade of Como cathedral, or “ heroa ” to unsaintly

mortals, such as that erected at Rimini by Sigismondo

Pandolfo in honour of Isotta,1 grew up side by side with

shrines and churches dedicated to the saints. We have

seen how the youthful vigour of the Christian faith vivified

for a time the dry bones of expiring classic art, and now

the decay of this same belief brought with it the destruc¬

tion of all that was most valuable in mediaeval sculpture.

Sculpture like the other arts became the bond-slave of the

rich and ceased to be the natural expression of a whole

people. Though for a long time in Italy great technical

skill continued to exist, the vivifying spirit was dead, and

at last a dull scholasticism or a riotous extravagance of

design became the leading characteristics.

1 See Yriarte, Rimini au XVme Siecle, Paris, 1880 ; also the article

Rimini.

The 16 th century was one of transition to this state of Sixteenth

degradation, but nevertheless produced many sculptors of century,

great ability who were not wholly crushed by the declining

taste of their time. John of Douay (1524-1608), usually

known as Giovanni da Bologna, one of the ablest, lived and

worked almost entirely in Italy. His bronze statue of

Mercury flying upwards, in the Uffizi, one of his finest

works, is full of life and

movement. By him also is

the Carrying off of a Sabine

Woman in the Loggia de’

Lanzi. His great fountain

at Bologna, with two tiers

of boys and mermaids, sur¬

mounted by a colossal statue

of Neptune, a very noble

work, is composed of archi¬

tectural features combined

with sculpture, and is remark¬

able for beauty of proportion.

He also cast the fine bronze

equestrian statue of Cosimo

de’ Medici at Florence and

the very richly decorated

west door of Pisa cathedral,

the latter much injured by

the over-crowding of its orna¬

ments and the want of sculp¬

turesque dignity in the fig¬

ures ; it is a feeble copy of

Ghiberti’s noble production.

One of Giovanni’s best works,

a group of two nude figures

fighting, is now lost. A fine

copy in lead existed till 20.—Group by Giovanni da Bo-

recently in the front quad-

rangle of Brasenose Cof-

lege, Oxford, of which it was the chief ornament (see fig.

20). In 1881 it was sold for old lead by the master and

fellows of the college, and was

immediately melted down by

the plumber who bought it—

a quite irreparable loss, as the

only other existing copy is

very inferior; the destruction

was an utterly inexcusable act

of vandalism. The sculpture

on the western fagade of the

church at Loreto and the ela¬

borate bronze gates of the

Santa Casa are works of great

technical merit by Girolamo

Lombardo and his sons, about

the middle of the 16th cen¬

tury. Benvenuto Cellini (1500-

1569), though in the main a

poor sculptor, produced one

work of great beauty and dig¬

nity,—the colossal bronze Per¬

seus at Florence (see fig. 21).

His large bust of Cosimo de’

Medici in the Bargello is mean

and petty in style. A num¬

ber of very clever statues and

groups in terra-cotta were Fig. 21.—Bronze statue of Per-

modelled by Antonio Begarelli seus and Medu,sa Cellini-in

of Modena (d. 1565), and t^LoggM de La™ »t Flor-

were enthusiastically admired

by Michelangelo; the finest are a Pi eta in S. Maria Pom-

posa and a large Descent from the Cross in S. Francesco,

XXL — 72

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (579) Page 569 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634806 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|