Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(578) Page 568

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

568

SCULPTURE

[ITALIAN.

alone in its best days could have rivalled. The similarity

between the plastic arts of Athens in the 5th or 4th cen¬

tury B.c. and of Florence in the 15th century is not one of

analogy only. Though free from any touch of copyism,

there are many points in the works of such men as Dona¬

tello, Luca della Robbia, and Vittore Pisanello which

strongly recall the sculpture of ancient Greece, and suggest

that, if a sculptor of the later Phidian school had been

surrounded by the same types of face and costume as those

among which the Italians lived, he would have produced

plastic works closely resembling those of the great Floren¬

tine masters. In the 14th century, in northern Italy,

various schools of sculpture existed, especially at Verona

and Venice, whose art differed widely from the contem¬

porary art of Tuscany; but Milan and Pavia, on the other

hand, possessed sculptors who followed closely the style

of the Pisani. The chief examples of the latter class are

the magnificent shrine of St Augustine in the cathedral of

Pavia, dated 1362, and the somewhat similar shrine of

Peter the Martyr (1339), by Balduccio of Pisa, in the

church of St Eustorgio at Milan, both of white marble,

decorated in the most lavish way with statuettes and

subject reliefs. Many other fine pieces of the Pisan school

exist in Milan. The well-known tombs of the Scaliger

family at Verona show a more native style of design, and

in general form, though not in detail, suggest the influence

of transalpine Gothic. In

Venice the northern and

almost French character

of much of the early 15th-

century sculpture is more

strongly marked, especi¬

ally in the noble figures

in high relief which de¬

corate the lower story and

angles of thedoge’s palace;1

these are mostly the work

of a Venetian named Bar¬

tolomeo Bon. A magni¬

ficent marble tympanum

relief by Bon has recently

been added to the South

Kensington Museum; it

has a noble colossal figure

of the Madonna, who shel¬

ters under her mantle a

number of kneeling wor¬

shippers ; the background

is enriched with foliage

and heads, forming a

“Jesse tree,” designed

with great decorative skill.

The cathedral of Como,

built at the very end of

the 15th century, is de¬

corated with good sculp¬

ture of almost Gothic style,

but on the whole rather

dull and mechanical in de¬

tail, like much of the sculp¬

ture in the extreme north

of Italy. A large quantity

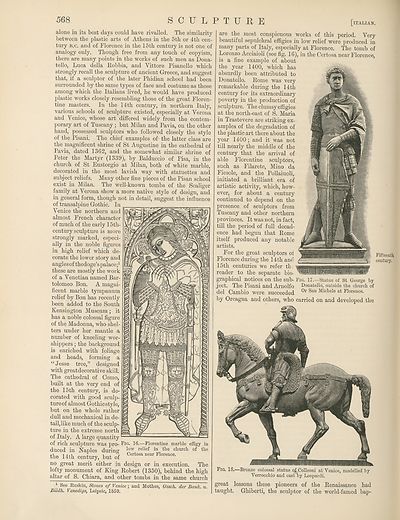

of rich sculpture was pro- Fig. 16.—Florentine marble effigy in

duced in Maples durin" ^ow re^ef in the church of the

the 14th century, but o°f Certosa near Florence-

no great merit either in design or in execution. The

lofty monument of King Robert (1350), behind the high

altar of S. Chiara, and other tombs in the same church

1 See Ruskin, Stones of Venice ; and Mothes, Gesch. der Bank. u.

Bildh. Venedigs, Leipsic, 1859.

are the most conspicuous works of this period. Very

beautiful sepulchral effigies in low relief were produced in

many parts of Italy, especially at Florence. The tomb of

Lorenzo Acciaioli (see fig. 16), in the Certosa near Florence,

is a fine example of about

till nearly the middle of the

century that the arrival of

able Florentine sculptors,

such as Filarete, Mino da

Fiesole, and the Pollaiuoli,

initiated bnlliant cta^oj ^

graphical notices on the sub- Fig. 17.—Statue of St George by

ject. The Pisani and Arnolfo Donatello, outside the church of

del Cambio were succeeded ^an Michele at Florence,

by Orcagna and others, who carried on and developed the

Fig. 18.—Bronze colossal statue of Colleoni at Venice, modelled by

Verrocchio and cast by Leopardi.

great lessons these pioneers of the Renaissance had

taught. Ghiberti, the sculptor of the world-famed bap-

SCULPTURE

[ITALIAN.

alone in its best days could have rivalled. The similarity

between the plastic arts of Athens in the 5th or 4th cen¬

tury B.c. and of Florence in the 15th century is not one of

analogy only. Though free from any touch of copyism,

there are many points in the works of such men as Dona¬

tello, Luca della Robbia, and Vittore Pisanello which

strongly recall the sculpture of ancient Greece, and suggest

that, if a sculptor of the later Phidian school had been

surrounded by the same types of face and costume as those

among which the Italians lived, he would have produced

plastic works closely resembling those of the great Floren¬

tine masters. In the 14th century, in northern Italy,

various schools of sculpture existed, especially at Verona

and Venice, whose art differed widely from the contem¬

porary art of Tuscany; but Milan and Pavia, on the other

hand, possessed sculptors who followed closely the style

of the Pisani. The chief examples of the latter class are

the magnificent shrine of St Augustine in the cathedral of

Pavia, dated 1362, and the somewhat similar shrine of

Peter the Martyr (1339), by Balduccio of Pisa, in the

church of St Eustorgio at Milan, both of white marble,

decorated in the most lavish way with statuettes and

subject reliefs. Many other fine pieces of the Pisan school

exist in Milan. The well-known tombs of the Scaliger

family at Verona show a more native style of design, and

in general form, though not in detail, suggest the influence

of transalpine Gothic. In

Venice the northern and

almost French character

of much of the early 15th-

century sculpture is more

strongly marked, especi¬

ally in the noble figures

in high relief which de¬

corate the lower story and

angles of thedoge’s palace;1

these are mostly the work

of a Venetian named Bar¬

tolomeo Bon. A magni¬

ficent marble tympanum

relief by Bon has recently

been added to the South

Kensington Museum; it

has a noble colossal figure

of the Madonna, who shel¬

ters under her mantle a

number of kneeling wor¬

shippers ; the background

is enriched with foliage

and heads, forming a

“Jesse tree,” designed

with great decorative skill.

The cathedral of Como,

built at the very end of

the 15th century, is de¬

corated with good sculp¬

ture of almost Gothic style,

but on the whole rather

dull and mechanical in de¬

tail, like much of the sculp¬

ture in the extreme north

of Italy. A large quantity

of rich sculpture was pro- Fig. 16.—Florentine marble effigy in

duced in Maples durin" ^ow re^ef in the church of the

the 14th century, but o°f Certosa near Florence-

no great merit either in design or in execution. The

lofty monument of King Robert (1350), behind the high

altar of S. Chiara, and other tombs in the same church

1 See Ruskin, Stones of Venice ; and Mothes, Gesch. der Bank. u.

Bildh. Venedigs, Leipsic, 1859.

are the most conspicuous works of this period. Very

beautiful sepulchral effigies in low relief were produced in

many parts of Italy, especially at Florence. The tomb of

Lorenzo Acciaioli (see fig. 16), in the Certosa near Florence,

is a fine example of about

till nearly the middle of the

century that the arrival of

able Florentine sculptors,

such as Filarete, Mino da

Fiesole, and the Pollaiuoli,

initiated bnlliant cta^oj ^

graphical notices on the sub- Fig. 17.—Statue of St George by

ject. The Pisani and Arnolfo Donatello, outside the church of

del Cambio were succeeded ^an Michele at Florence,

by Orcagna and others, who carried on and developed the

Fig. 18.—Bronze colossal statue of Colleoni at Venice, modelled by

Verrocchio and cast by Leopardi.

great lessons these pioneers of the Renaissance had

taught. Ghiberti, the sculptor of the world-famed bap-

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (578) Page 568 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634793 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|