Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(580) Page 570

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

570

both at Modena. The colossal bronze seated statue of

Julius III. at Perugia, cast in 1555 by Vincenzo Danti, is

one of the best portrait-figures of the time.

Seven- The chief sculptor and architect of the 17th century was

century tlie NeaPolitan Bernini (1598-1680), who, with the aid of

a large school of assistants, produced an almost incredible

quantity of sculpture of the most varying degrees of merit

and hideousness. His chief early group, the Apollo and

Daphne in the Borghese casino, is a work of wonderful

technical skill and delicate high finish, combined with soft

beauty and grace, though too pictorial in style. In later

life Bernini turned out work of brutal coarseness,1 designed

in a thoroughly unsculpturesque spirit. The churches of

Borne, the colonnade of St Peter’s, and the bridge of S.

Angelo are crowded with his clumsy colossal figures, half

draped in wildly fluttering garments,—perfect models of

what is worst in the plastic art. And yet his works re¬

ceived perhaps more praise than those of any other sculptor

of any age, and after his death a scaffolding was erected

outside the bridge of S. Angelo in order that people might

walk round and admire his rows of feeble half-naked

angels. For all that, Bernini was a man of undoubted

talent, and in a better period of art would have been a

sculptor of the first rank ; many of his portrait-busts are

works of great vigour and dignity, quite free from the

mannered extravagance of his larger sculpture. Stefano

Maderna (15/1-1636) was the ablest of his contempo¬

raries ; his clever and much admired statue, the figure of

the dead S. Cecilia under the high altar of her basilica,

is chiefly remarkable for its deathlike pose and the realistic

treatment of the drapery. Another clever sculptor was

Alessandro Algardi of Bologna (1598M654).

SS’ In the.next century at Naples Queirolo, Corradini, and

century. Sammartino produced a number of statues, now in the

chapel of S. Maria de’ Sangri, which are extraordinary

examples of wasted labour and ignorance of the simplest

canons of plastic art. These are marble statues enmeshed

in nets or covered with thin veils, executed with almost

deceptive realism, perhaps the lowest stage of tricky de¬

gradation into which the sculptor’s art could possibly fall.2

In the 18th century Italy was naturally the headquarters

of the classical revival, which spread thence throughout

most of Europe. Canova (1757-1822), a Venetian by

birth, who spent most of his life in Rome, was perhaps

the leading spirit of this movement, and became the most

popular sculptor of his time. His work is very unequal in

merit, moetly dull and uninteresting in style, and is occa¬

sionally marred by a meretricious spirit very contrary to

the true classic feeling. His group of the Three Graces,

the Hebe, and the very popular Dancing-Girls, copies of

which in plaster disfigure the stairs of countless modern

hotels and other buildings on the Continent, are typical

examples of Canova's worst work. Some of his sculpture

is designed with far more of the purity of antique art;

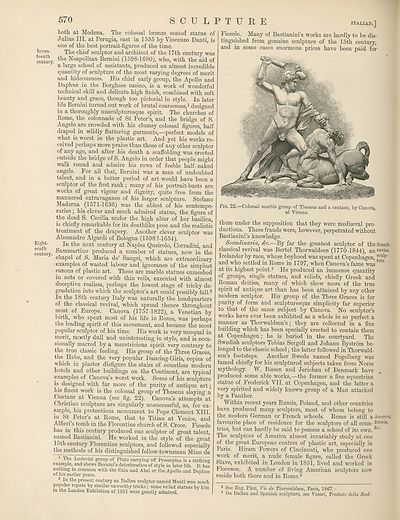

his finest work is the colossal group of Theseus slaying a

Centaur at Vienna (see fig. 22). Canova’s attempts at

Christian sculpture are singularly unsuccessful, as, for ex¬

ample, his pretentious monument to Pope Clement XIII.

in St Peters at Rome, that to Titian at Venice, and

Alfieri’s tomb in the Florentine church of S. Croce. Fiesole

has in this century produced one sculptor of great talent,

named Bastianini. He worked in the style of the great

15th-century Florentine sculptors, and followed especially

the methods of his distinguished fellow-townsman Mino da

The Ludovisi group of Pluto carrying off Proserpine is a striking

example, and shows Bernini’s deterioration of style in later life It has

nothing in common with the Cain and Abel or the Apollo and Daphne

of his earlier years.

In the present century an Italian sculptor named. Monti won much

popuiar repute by similar unworthy tricks ; some veiled statues by him

m the London Exhibition of 1851 were greatly admired.

ITALIAN.]

Fiesole. Many of Bastianini’s works are hardly to be dis¬

tinguished from genuine sculpture of the 15th century,

and in some cases enormous prices have been paid for

Fig. 22.—Colossal marble group of Theseus and a centaur, by Canova,

at Vienna.

them under the supposition that they were mediteval pro¬

ductions. These frauds were, however, perpetrated without

Bastianini’s knowledge.

Scandinavia, &c.—By far the greatest sculptor of the Scandi-

classical revival was Bertel Thorwaldsen (1770-1844), annaviai1

Icelander by race, whose boyhood was spent at Copenhagen,sculp'

and who settled in Rome in 1797, when Canova’s fame was °rs

at its highest point.3 He produced an immense quantity

of groups, single statues, and reliefs, chiefly Greek and

Roman deities, many of which show more of the true

spirit of antique art than has been attained by any other

modern sculptor. His group of the Three Graces is for

purity of form and sculpturesque simplicity far superior

to that of the same subject by Canova. No sculptor’s

works have ever been exhibited as a whole in so perfect a

manner as Thorwaldsen’s; they are collected in a fine

building which has been specially erected to contain them

at Copenhagen; he is buried in the courtyard. The

Swedish sculptors Tobias Sergell and Johann Bystrom be¬

longed to the classic school; the latter followed in Thorwald¬

sen s footsteps. Another Swede named Fogelberg was

famed chiefly for his sculptured subjects taken from Norse

mythology, W. Bissen and Jerichau of Denmark have

produced some able works,—the former a fine equestrian

statue of Frederick VII. at Copenhagen, and the latter a

very spirited and widely known-group of a Man attacked

by a Panther.

Within recent years Russia, Poland, and other countries

have produced many sculptors, most of whom belong to

the modern German or French schools. Rome is still a America,

favourite place of residence for the sculptors of all coun- Russ‘a>

tries, but can hardly be said to possess a school of its own. &c'

The sculptors of America almost invariably study at one

of the great European centres of plastic art, especially in

Paris. Hiram Powers of Cincinnati, who produced one

work of merit, a nude female figure, called the Greek

Slave, exhibited in London in 1851, lived and worked in

Florence. A number of living American sculptors now

reside both there and in Rome.4

3 See Eug. Plon, Vie de Thorwaldsen, Paris, 1867.

4 On Italian and Spanish sculpture, see Vasari, Trattato della Sail-

SCULPTURE

both at Modena. The colossal bronze seated statue of

Julius III. at Perugia, cast in 1555 by Vincenzo Danti, is

one of the best portrait-figures of the time.

Seven- The chief sculptor and architect of the 17th century was

century tlie NeaPolitan Bernini (1598-1680), who, with the aid of

a large school of assistants, produced an almost incredible

quantity of sculpture of the most varying degrees of merit

and hideousness. His chief early group, the Apollo and

Daphne in the Borghese casino, is a work of wonderful

technical skill and delicate high finish, combined with soft

beauty and grace, though too pictorial in style. In later

life Bernini turned out work of brutal coarseness,1 designed

in a thoroughly unsculpturesque spirit. The churches of

Borne, the colonnade of St Peter’s, and the bridge of S.

Angelo are crowded with his clumsy colossal figures, half

draped in wildly fluttering garments,—perfect models of

what is worst in the plastic art. And yet his works re¬

ceived perhaps more praise than those of any other sculptor

of any age, and after his death a scaffolding was erected

outside the bridge of S. Angelo in order that people might

walk round and admire his rows of feeble half-naked

angels. For all that, Bernini was a man of undoubted

talent, and in a better period of art would have been a

sculptor of the first rank ; many of his portrait-busts are

works of great vigour and dignity, quite free from the

mannered extravagance of his larger sculpture. Stefano

Maderna (15/1-1636) was the ablest of his contempo¬

raries ; his clever and much admired statue, the figure of

the dead S. Cecilia under the high altar of her basilica,

is chiefly remarkable for its deathlike pose and the realistic

treatment of the drapery. Another clever sculptor was

Alessandro Algardi of Bologna (1598M654).

SS’ In the.next century at Naples Queirolo, Corradini, and

century. Sammartino produced a number of statues, now in the

chapel of S. Maria de’ Sangri, which are extraordinary

examples of wasted labour and ignorance of the simplest

canons of plastic art. These are marble statues enmeshed

in nets or covered with thin veils, executed with almost

deceptive realism, perhaps the lowest stage of tricky de¬

gradation into which the sculptor’s art could possibly fall.2

In the 18th century Italy was naturally the headquarters

of the classical revival, which spread thence throughout

most of Europe. Canova (1757-1822), a Venetian by

birth, who spent most of his life in Rome, was perhaps

the leading spirit of this movement, and became the most

popular sculptor of his time. His work is very unequal in

merit, moetly dull and uninteresting in style, and is occa¬

sionally marred by a meretricious spirit very contrary to

the true classic feeling. His group of the Three Graces,

the Hebe, and the very popular Dancing-Girls, copies of

which in plaster disfigure the stairs of countless modern

hotels and other buildings on the Continent, are typical

examples of Canova's worst work. Some of his sculpture

is designed with far more of the purity of antique art;

his finest work is the colossal group of Theseus slaying a

Centaur at Vienna (see fig. 22). Canova’s attempts at

Christian sculpture are singularly unsuccessful, as, for ex¬

ample, his pretentious monument to Pope Clement XIII.

in St Peters at Rome, that to Titian at Venice, and

Alfieri’s tomb in the Florentine church of S. Croce. Fiesole

has in this century produced one sculptor of great talent,

named Bastianini. He worked in the style of the great

15th-century Florentine sculptors, and followed especially

the methods of his distinguished fellow-townsman Mino da

The Ludovisi group of Pluto carrying off Proserpine is a striking

example, and shows Bernini’s deterioration of style in later life It has

nothing in common with the Cain and Abel or the Apollo and Daphne

of his earlier years.

In the present century an Italian sculptor named. Monti won much

popuiar repute by similar unworthy tricks ; some veiled statues by him

m the London Exhibition of 1851 were greatly admired.

ITALIAN.]

Fiesole. Many of Bastianini’s works are hardly to be dis¬

tinguished from genuine sculpture of the 15th century,

and in some cases enormous prices have been paid for

Fig. 22.—Colossal marble group of Theseus and a centaur, by Canova,

at Vienna.

them under the supposition that they were mediteval pro¬

ductions. These frauds were, however, perpetrated without

Bastianini’s knowledge.

Scandinavia, &c.—By far the greatest sculptor of the Scandi-

classical revival was Bertel Thorwaldsen (1770-1844), annaviai1

Icelander by race, whose boyhood was spent at Copenhagen,sculp'

and who settled in Rome in 1797, when Canova’s fame was °rs

at its highest point.3 He produced an immense quantity

of groups, single statues, and reliefs, chiefly Greek and

Roman deities, many of which show more of the true

spirit of antique art than has been attained by any other

modern sculptor. His group of the Three Graces is for

purity of form and sculpturesque simplicity far superior

to that of the same subject by Canova. No sculptor’s

works have ever been exhibited as a whole in so perfect a

manner as Thorwaldsen’s; they are collected in a fine

building which has been specially erected to contain them

at Copenhagen; he is buried in the courtyard. The

Swedish sculptors Tobias Sergell and Johann Bystrom be¬

longed to the classic school; the latter followed in Thorwald¬

sen s footsteps. Another Swede named Fogelberg was

famed chiefly for his sculptured subjects taken from Norse

mythology, W. Bissen and Jerichau of Denmark have

produced some able works,—the former a fine equestrian

statue of Frederick VII. at Copenhagen, and the latter a

very spirited and widely known-group of a Man attacked

by a Panther.

Within recent years Russia, Poland, and other countries

have produced many sculptors, most of whom belong to

the modern German or French schools. Rome is still a America,

favourite place of residence for the sculptors of all coun- Russ‘a>

tries, but can hardly be said to possess a school of its own. &c'

The sculptors of America almost invariably study at one

of the great European centres of plastic art, especially in

Paris. Hiram Powers of Cincinnati, who produced one

work of merit, a nude female figure, called the Greek

Slave, exhibited in London in 1851, lived and worked in

Florence. A number of living American sculptors now

reside both there and in Rome.4

3 See Eug. Plon, Vie de Thorwaldsen, Paris, 1867.

4 On Italian and Spanish sculpture, see Vasari, Trattato della Sail-

SCULPTURE

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (580) Page 570 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634819 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|