Topographical, statistical, and historical gazetteer of Scotland > Volume 1

(46) Page xxxiv

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

xxxiv

INTRODUCTION.

extent, checked in turn by their vassals. A jury of barons, who were not members of

parliament, might sit on a lord's case, of even the gravest character, and might decide it

without being unanimous in their verdict ; and the vassals of a baron so completely in-

volved or concentrated all his available power in their own fidelity and attachment, as

to oblige him, in many respects, to act more in the character of the father of his clan

than in that of a military despot. The king, too, — while denied nearly all strictly royal

prerogatives by the constitution of the country, — was indemnified for most by the acci-

dents of its feudal institutions. He acquired considerable interest among the burgesses

and lower ranks in consequence of the abuse of power by the lords and great landowners ;

and, when he had sufficient address to retain the affections of the people, he was gene-

rally able to humble the most powerful and dominant confederacy of the aristocrats ;

though, when he did not acquire popularity, he might dare to disregard the parliament

only at the hazard of his crown or his life. The kings, — aided by the clergy, whose

revenues were vast, and who were strongly jealous of the power of the nobility, — even-

tually succeeded in greatly diminishing, and, at times, entirely neutralizing-, the aristo-

cratical power of parliament. A select body of members was established, from among

the clergy, the nobility, the knights, and the burgesses, and called " the Lords of the

Articles ;" it was produced by the bishops choosing 8 peers, and the peers 8 bishops,

by the 16 who were elected choosing 8 barons or knights of the shires, and 8 commis-

sioners of royal burghs, and by 8 great officers of state being added to the whole, with

the Lord-chancellor as president ; its business was to prepare all questions, bills, and

other matters, to be brought before parliament ; and the clerical part of it being in strict

alliance with the king, while the civilian part was not a little influenced by his great

powers of patronage, it effectually prevented the introduction to parliament of any affair

which was unsuited to his views, and gave him very stringently all the powers of a real

veto. This institution seems to have been introduced by stealth, and never brought to a

regular plan ; and as to its date and early history, it baffles the research, or at least

defies the unanimity, of the best informed law writers. Yet " the Lords of the Articles "

were far from being wholly subservient to the Crown ; for they not only resisted the

efforts of Charles I. to make them mere tools of his despotism, but went freely down the

current which swept that infatuated monarch to his melancholy fate ; and, at the Revo-

lution, they waived all ceremony about getting from the fanatical idiot, James VII., a

formal deed of abdication, and promptly united in a summary declaration that he had

forfeited his crown. Before the Union there were four great officers of state, the Lord

High-chancellor, the High-treasurer, the Privy-seal, and the Secretary, — and four lesser

officers, the Lord Clerk-register, the Lord-advocate, the Treasurer-depute, and the

Justice-clerk, — all of whom sat, ex-officio, in parliament. The officers of state and the

law courts which now exist, will be found noticed in our article on Edinburgh. The

privy council of Scotland, previous to the Revolution, assumed inquisitorial powers, even

that of torture ; but it is now swamped in the privy council of Great Britain. Tho

Scottish nobility return from among their own number 16 peers to represent them in the

tipper house of the imperial parliament. Between the Union and the date of the Reform

bill, the freeholders of the counties, who amounted even at the last to only 3,211 in

number, returned to the House of Commons 30 members ; the city of Edinburgh

returned 1 ; and the other royal burghs, 6-5 in number, and classified into districts.

The Parliamentary Reform act in 1832, added, at the first impulse, 29,904 to the

aggregate constituency of the counties ; but it allowed them only the same number of

representatives as before, — erecting Kinross, Clackmannan, and some adjoining portions

of Perth and Stirling, into one electoral district ; conjoining Cromarty with Ross and

Nairn with Elgin, and assigning one member to each of the other counties. The same

act enfranchised various towns, or erected them into parliamentary burghs, increased the

burgh constituency from a pitiful number to upwards of 31,000, and raised the aggregate

number of representatives from 14 to 23. The total constituencies of the counties and

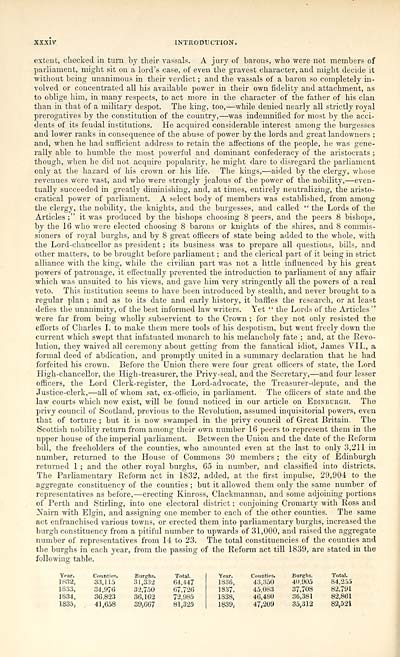

the burghs in each year, from the passing of the Reform act till 1839, are stated in the

following table.

Year.

Counties.

Burphs.

Total.

Year.

Counties.

Burghs.

Total.

1832,

33,115

3 1 ,332

64,447

1836,

43,350

40,905

84,255

1833,

34,976

32,750

67,726

18.37,

45,083

37,708

82,791

18.34,

36,823

36,162

72,985

1838,

46,480

36,381

82,861

1835,

41,658

39,667

81,325

1839,

47,209

35,312

82,521

INTRODUCTION.

extent, checked in turn by their vassals. A jury of barons, who were not members of

parliament, might sit on a lord's case, of even the gravest character, and might decide it

without being unanimous in their verdict ; and the vassals of a baron so completely in-

volved or concentrated all his available power in their own fidelity and attachment, as

to oblige him, in many respects, to act more in the character of the father of his clan

than in that of a military despot. The king, too, — while denied nearly all strictly royal

prerogatives by the constitution of the country, — was indemnified for most by the acci-

dents of its feudal institutions. He acquired considerable interest among the burgesses

and lower ranks in consequence of the abuse of power by the lords and great landowners ;

and, when he had sufficient address to retain the affections of the people, he was gene-

rally able to humble the most powerful and dominant confederacy of the aristocrats ;

though, when he did not acquire popularity, he might dare to disregard the parliament

only at the hazard of his crown or his life. The kings, — aided by the clergy, whose

revenues were vast, and who were strongly jealous of the power of the nobility, — even-

tually succeeded in greatly diminishing, and, at times, entirely neutralizing-, the aristo-

cratical power of parliament. A select body of members was established, from among

the clergy, the nobility, the knights, and the burgesses, and called " the Lords of the

Articles ;" it was produced by the bishops choosing 8 peers, and the peers 8 bishops,

by the 16 who were elected choosing 8 barons or knights of the shires, and 8 commis-

sioners of royal burghs, and by 8 great officers of state being added to the whole, with

the Lord-chancellor as president ; its business was to prepare all questions, bills, and

other matters, to be brought before parliament ; and the clerical part of it being in strict

alliance with the king, while the civilian part was not a little influenced by his great

powers of patronage, it effectually prevented the introduction to parliament of any affair

which was unsuited to his views, and gave him very stringently all the powers of a real

veto. This institution seems to have been introduced by stealth, and never brought to a

regular plan ; and as to its date and early history, it baffles the research, or at least

defies the unanimity, of the best informed law writers. Yet " the Lords of the Articles "

were far from being wholly subservient to the Crown ; for they not only resisted the

efforts of Charles I. to make them mere tools of his despotism, but went freely down the

current which swept that infatuated monarch to his melancholy fate ; and, at the Revo-

lution, they waived all ceremony about getting from the fanatical idiot, James VII., a

formal deed of abdication, and promptly united in a summary declaration that he had

forfeited his crown. Before the Union there were four great officers of state, the Lord

High-chancellor, the High-treasurer, the Privy-seal, and the Secretary, — and four lesser

officers, the Lord Clerk-register, the Lord-advocate, the Treasurer-depute, and the

Justice-clerk, — all of whom sat, ex-officio, in parliament. The officers of state and the

law courts which now exist, will be found noticed in our article on Edinburgh. The

privy council of Scotland, previous to the Revolution, assumed inquisitorial powers, even

that of torture ; but it is now swamped in the privy council of Great Britain. Tho

Scottish nobility return from among their own number 16 peers to represent them in the

tipper house of the imperial parliament. Between the Union and the date of the Reform

bill, the freeholders of the counties, who amounted even at the last to only 3,211 in

number, returned to the House of Commons 30 members ; the city of Edinburgh

returned 1 ; and the other royal burghs, 6-5 in number, and classified into districts.

The Parliamentary Reform act in 1832, added, at the first impulse, 29,904 to the

aggregate constituency of the counties ; but it allowed them only the same number of

representatives as before, — erecting Kinross, Clackmannan, and some adjoining portions

of Perth and Stirling, into one electoral district ; conjoining Cromarty with Ross and

Nairn with Elgin, and assigning one member to each of the other counties. The same

act enfranchised various towns, or erected them into parliamentary burghs, increased the

burgh constituency from a pitiful number to upwards of 31,000, and raised the aggregate

number of representatives from 14 to 23. The total constituencies of the counties and

the burghs in each year, from the passing of the Reform act till 1839, are stated in the

following table.

Year.

Counties.

Burphs.

Total.

Year.

Counties.

Burghs.

Total.

1832,

33,115

3 1 ,332

64,447

1836,

43,350

40,905

84,255

1833,

34,976

32,750

67,726

18.37,

45,083

37,708

82,791

18.34,

36,823

36,162

72,985

1838,

46,480

36,381

82,861

1835,

41,658

39,667

81,325

1839,

47,209

35,312

82,521

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Gazetteers of Scotland, 1803-1901 > Topographical, statistical, and historical gazetteer of Scotland > Volume 1 > (46) Page xxxiv |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/97438098 |

|---|

| Description | Volume first. A-H. |

|---|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|