Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

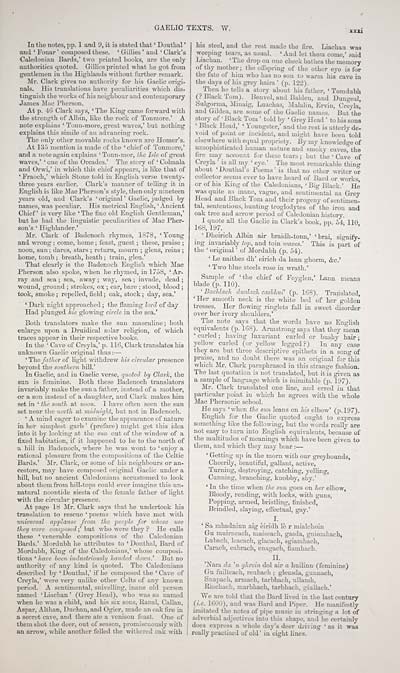

GAELIC TEXTS. W.

In the notes, pp. 1 and 9, it is stated tliat ' Doutbal '

and ' Fonar ' composed these. ' Gilhes ' and ' Clark's

Caledonian Bards,' two printed books, are the only

authorities quoted. Gillies printed what ho got from

gentlemen iu the Highlands without further remark.

Mr. Clark gives no authority for his Gaelic origi-

nals. His translations have peculiarities which dis-

tinguish the works of his neighbour and contemporary

■James Mac Pherson.

At p. 46 Clark says, ' The King came forward with

the strength of Albin, like the rock of Tonmore.' A

note explains ' Tonn-moro, great waves,' but nothing

explains this simile of an advancing rock.

The only other movable rocks known are Homer's.

At 135 mention is made of the 'chief of Tonmore,'

and a note again explains ' Tonn-mor, tlto Isle of great

waves,' ' one of the Orcadcs.' The story of ' Cohnala

and Orwi,' in which this chief appears, is like that of

' Fraoch,' which Stone told in English verse twenty-

three years earlier. Clark's manner of telbng it in

English is like Mac Pherson's style, then only nineteen

years old, and Clark's ' original ' Gaelic, judged by

names, was peculiar. His metrical English, ' Ancient

Chief is very like 'The fine old English Gentleman,'

but he liad the linguistic peculiarities of Mao Pher-

son's ' Highlander.'

Mr. Clark of Badenoch rhymes, 1878, 'Toung

and ■wrong ; come, home ; feast, guest ; these, praise ;

noon, sun ; dares, stars ; return, mourn ; glens, reins ;

home, tomb ; breath, heath ; train, glen.'

That cleai-ly is the Badenoch English which Mao

Pherson also spoke, when he rhymed, in 1758, 'Ar-

ray and sea ; sea, away ; way, sea ; invade, dead ;

wound, ground ; strokes, ox ; ear, bare ; stood, blood ;

took, smoke ; repelled, field ; oak, stock ; day, sea.'

' Dark night approached ; the flaming lord of day

Had plunged his glowing circle in the sea.'

Both translators make the sun masculine ; both

enlarge upon a Druidical solar religion, of which

traces appear in their respective books.

In the ' Cave of Creyla,' p. 116, Clark translates his

unknown Gaelic original thus : —

' The father of light withdrew Ms circular presence

beyond the soidliern hill.'

In Gaelic, and in Gaelic verse, quoted hy Clark, the

sun is feminine. Both these Badenoch translators

invariably make the sun a father, instead of a mother,

or a son instead of a daughter, and Clark makes him

set in ' the south at noon. I have often seen the sun

set near the north at midnight, but not in Badenoch.

' A mind eager to examine the appearance of nature

in her simplest garb ' (preface) might get this idea

into it by looking at the sun out of the window of a

fixed habitation, if it happened to be to the north of

a hill in Badenoch, where he was wont to ' enjoy a

rational pleasure from the compositions of the Celtic

Bards.' Mr. Clark, or some of his neighbours or an-

cestors, may have composed original Gaelic under a

hill, but no ancient Caledonians accustomed to look

about them from hill-tops could ever imagine this un-

natural noontide siesta of the female father of light

with the circular presence.

At page 18 Mr. Clark says that he undertook his

translation to rescue ' poems which have met with

nniversal applause from the people for v-hose use

they were composed ;' but who were they ? He calls

these ' venerable compositions of the Caledonian

Bai-ds.' Mordubh he attributes to ' Douthal, Bard of

Mordubh, King of the Caledonians,' whose composi-

tions ' liuve been industriously handed doivn.' But no

authority of any kind is quoted. The Caledonians

described by 'Douthal,' if he composed the 'Cave of

Creyla,' were very unlike other Celts of any known

period. A sentimental, snivelling, inane old person

named 'Liachan' (Grey Head), who was so named

when lie was a child, and his six sons, Ranal, Callan,

Aspar, Althan, Duchan, and Ogier, made an oak fire in

a secret cave, and there ate a venison feast. One of

them shot the deer, out of season, promiscuously with

an arrow, while another felled the withered oak with

his steel, and the rest made the fire. Liachan was

weejjing tears, as usual. 'And let them come,' said

Jjiachan. ' The drop on one cheek bathes the memory

of thy mother ; the ollspring of the other eye is for

the fote of him who has no son ta warm his cavo in

the days of his grey hairs ' (p. 122).

Then he tells a story about his father, ' Tomdubh

(? Black Tom). Benvel, and Balden, and Dungeal,

Sulgorma, Miuaig, Luaehas, Jlalalin, Krvin, Creyla,

and Gildea, are some of the Gaelic names. But the

story of ' Black Tom ' told by ' Grey Head ' to his sona

' Black Head,' ' Youngster,' and the rest is utterly de-

void of point or incident, and might have been told

elsewherowith equal propriety. By my knowledge of

unsophisticated human nature and smoky caves^the

fire may account for these tears ; but the ' Cave of

Creyla ' is all my ' eye.' The most remarkable thing

about ' Douthal's Poems ' is that no other writer or

collector seems ever to have heard of Bard or works,

or of his King of the Caledonians, 'Big Black.' He

was quite as mane, vague, and sentimental as Grey

Head and Black Tom and their progeny of sentimen-

tal, sententious, hunting troglodytes of the iron and

oak tree and arrow period of Caledonian history.

I quote all the Gaelic iu Clark's book, pp. 54 110

108, 197. ^^

' Dheirich Albin air braidh-tonn,' ' brai, signify-

ing invariably top, and toin waves' This is part of

the ' original ' of Mordubh (p. 54).

' Le naithes dh' eirich da lann ghorm, &c.'

' Two blue steels rose in -wrath.'

Sample of 'the chief of Feyglen,' Lann means

blade (p. 110).

' Bachlach dualach caslhui' (p. 168). Translated,

'Her smooth neck is the white bed of her golden

tresses. Her flowing ringlets fall in sweet disorder

over her ivory shoulders.'

The note says that the words have no EngHsh

equivalents (p. 168). Armstrong says that they mean

' curled ; having luxuriant curled or bushy hair ;

yellow curled (or yellow legged?) In any case

they are but three descriptive epithets in a sono- of

praise, and no doubt there was an original for this

which Mr. Clark paraphrased in this strange fashion.

The last quotation is not translated, but it is given as

a sample of language which is inimitable (p. 107).

Mr. Clark translated one line, and erred in that

particular point in which he agrees with the whole

Mac Phersonic school.

He says 'when the sun leans on his elbow' (p.l97).

English for the Gaelic quoted ought to express

something like the following, but the words really are

not easy to turn into English equivalents, because of

the multitudes of meanings which have been given to

them, and which they may bear : —

' Gettmg up in the morn with our greyhounds,

Cheerily, beautiful, gallant, active,

Turning, destroying, catching, yelling,

Cunning, branching, knobby, shy.'

' In the time when tlic sun goes on her elbow,

Bloody, rending, with locks, ivith guns.

Popping, armed, bristling, finished,

Brindled, slaying, effectual, gay.'

I.

' Sa mhadninn aig èiridh lè r mialchoin

Gu muirneach, maiseach, gasda, gniomhach,

Lubach, Icacach, glacach, sgiamhach,

Carach, cabrach, cnagach, fiamhach.

II.

'Nam da '« ghrein dol air a huilinn (feminine)

Gu fuilteach, reubach ; gleusda, gunnach,

Snapach, armach, tarbhach, ullamh,

Riachach, marbhach, tarbhacli, giullach.'

_ We are told that the Bard lived in the last centnry

(i.e. 1600), and was Bard and Piper. He manifestly

imitated the notes of pipe music in stringing a lot of

adverbial adjectives into this shape, and he certainly

does express a whole day's deer diiving ' as it was

really practised of old ' in eight lines.

In the notes, pp. 1 and 9, it is stated tliat ' Doutbal '

and ' Fonar ' composed these. ' Gilhes ' and ' Clark's

Caledonian Bards,' two printed books, are the only

authorities quoted. Gillies printed what ho got from

gentlemen iu the Highlands without further remark.

Mr. Clark gives no authority for his Gaelic origi-

nals. His translations have peculiarities which dis-

tinguish the works of his neighbour and contemporary

■James Mac Pherson.

At p. 46 Clark says, ' The King came forward with

the strength of Albin, like the rock of Tonmore.' A

note explains ' Tonn-moro, great waves,' but nothing

explains this simile of an advancing rock.

The only other movable rocks known are Homer's.

At 135 mention is made of the 'chief of Tonmore,'

and a note again explains ' Tonn-mor, tlto Isle of great

waves,' ' one of the Orcadcs.' The story of ' Cohnala

and Orwi,' in which this chief appears, is like that of

' Fraoch,' which Stone told in English verse twenty-

three years earlier. Clark's manner of telbng it in

English is like Mac Pherson's style, then only nineteen

years old, and Clark's ' original ' Gaelic, judged by

names, was peculiar. His metrical English, ' Ancient

Chief is very like 'The fine old English Gentleman,'

but he liad the linguistic peculiarities of Mao Pher-

son's ' Highlander.'

Mr. Clark of Badenoch rhymes, 1878, 'Toung

and ■wrong ; come, home ; feast, guest ; these, praise ;

noon, sun ; dares, stars ; return, mourn ; glens, reins ;

home, tomb ; breath, heath ; train, glen.'

That cleai-ly is the Badenoch English which Mao

Pherson also spoke, when he rhymed, in 1758, 'Ar-

ray and sea ; sea, away ; way, sea ; invade, dead ;

wound, ground ; strokes, ox ; ear, bare ; stood, blood ;

took, smoke ; repelled, field ; oak, stock ; day, sea.'

' Dark night approached ; the flaming lord of day

Had plunged his glowing circle in the sea.'

Both translators make the sun masculine ; both

enlarge upon a Druidical solar religion, of which

traces appear in their respective books.

In the ' Cave of Creyla,' p. 116, Clark translates his

unknown Gaelic original thus : —

' The father of light withdrew Ms circular presence

beyond the soidliern hill.'

In Gaelic, and in Gaelic verse, quoted hy Clark, the

sun is feminine. Both these Badenoch translators

invariably make the sun a father, instead of a mother,

or a son instead of a daughter, and Clark makes him

set in ' the south at noon. I have often seen the sun

set near the north at midnight, but not in Badenoch.

' A mind eager to examine the appearance of nature

in her simplest garb ' (preface) might get this idea

into it by looking at the sun out of the window of a

fixed habitation, if it happened to be to the north of

a hill in Badenoch, where he was wont to ' enjoy a

rational pleasure from the compositions of the Celtic

Bards.' Mr. Clark, or some of his neighbours or an-

cestors, may have composed original Gaelic under a

hill, but no ancient Caledonians accustomed to look

about them from hill-tops could ever imagine this un-

natural noontide siesta of the female father of light

with the circular presence.

At page 18 Mr. Clark says that he undertook his

translation to rescue ' poems which have met with

nniversal applause from the people for v-hose use

they were composed ;' but who were they ? He calls

these ' venerable compositions of the Caledonian

Bai-ds.' Mordubh he attributes to ' Douthal, Bard of

Mordubh, King of the Caledonians,' whose composi-

tions ' liuve been industriously handed doivn.' But no

authority of any kind is quoted. The Caledonians

described by 'Douthal,' if he composed the 'Cave of

Creyla,' were very unlike other Celts of any known

period. A sentimental, snivelling, inane old person

named 'Liachan' (Grey Head), who was so named

when lie was a child, and his six sons, Ranal, Callan,

Aspar, Althan, Duchan, and Ogier, made an oak fire in

a secret cave, and there ate a venison feast. One of

them shot the deer, out of season, promiscuously with

an arrow, while another felled the withered oak with

his steel, and the rest made the fire. Liachan was

weejjing tears, as usual. 'And let them come,' said

Jjiachan. ' The drop on one cheek bathes the memory

of thy mother ; the ollspring of the other eye is for

the fote of him who has no son ta warm his cavo in

the days of his grey hairs ' (p. 122).

Then he tells a story about his father, ' Tomdubh

(? Black Tom). Benvel, and Balden, and Dungeal,

Sulgorma, Miuaig, Luaehas, Jlalalin, Krvin, Creyla,

and Gildea, are some of the Gaelic names. But the

story of ' Black Tom ' told by ' Grey Head ' to his sona

' Black Head,' ' Youngster,' and the rest is utterly de-

void of point or incident, and might have been told

elsewherowith equal propriety. By my knowledge of

unsophisticated human nature and smoky caves^the

fire may account for these tears ; but the ' Cave of

Creyla ' is all my ' eye.' The most remarkable thing

about ' Douthal's Poems ' is that no other writer or

collector seems ever to have heard of Bard or works,

or of his King of the Caledonians, 'Big Black.' He

was quite as mane, vague, and sentimental as Grey

Head and Black Tom and their progeny of sentimen-

tal, sententious, hunting troglodytes of the iron and

oak tree and arrow period of Caledonian history.

I quote all the Gaelic iu Clark's book, pp. 54 110

108, 197. ^^

' Dheirich Albin air braidh-tonn,' ' brai, signify-

ing invariably top, and toin waves' This is part of

the ' original ' of Mordubh (p. 54).

' Le naithes dh' eirich da lann ghorm, &c.'

' Two blue steels rose in -wrath.'

Sample of 'the chief of Feyglen,' Lann means

blade (p. 110).

' Bachlach dualach caslhui' (p. 168). Translated,

'Her smooth neck is the white bed of her golden

tresses. Her flowing ringlets fall in sweet disorder

over her ivory shoulders.'

The note says that the words have no EngHsh

equivalents (p. 168). Armstrong says that they mean

' curled ; having luxuriant curled or bushy hair ;

yellow curled (or yellow legged?) In any case

they are but three descriptive epithets in a sono- of

praise, and no doubt there was an original for this

which Mr. Clark paraphrased in this strange fashion.

The last quotation is not translated, but it is given as

a sample of language which is inimitable (p. 107).

Mr. Clark translated one line, and erred in that

particular point in which he agrees with the whole

Mac Phersonic school.

He says 'when the sun leans on his elbow' (p.l97).

English for the Gaelic quoted ought to express

something like the following, but the words really are

not easy to turn into English equivalents, because of

the multitudes of meanings which have been given to

them, and which they may bear : —

' Gettmg up in the morn with our greyhounds,

Cheerily, beautiful, gallant, active,

Turning, destroying, catching, yelling,

Cunning, branching, knobby, shy.'

' In the time when tlic sun goes on her elbow,

Bloody, rending, with locks, ivith guns.

Popping, armed, bristling, finished,

Brindled, slaying, effectual, gay.'

I.

' Sa mhadninn aig èiridh lè r mialchoin

Gu muirneach, maiseach, gasda, gniomhach,

Lubach, Icacach, glacach, sgiamhach,

Carach, cabrach, cnagach, fiamhach.

II.

'Nam da '« ghrein dol air a huilinn (feminine)

Gu fuilteach, reubach ; gleusda, gunnach,

Snapach, armach, tarbhach, ullamh,

Riachach, marbhach, tarbhacli, giullach.'

_ We are told that the Bard lived in the last centnry

(i.e. 1600), and was Bard and Piper. He manifestly

imitated the notes of pipe music in stringing a lot of

adverbial adjectives into this shape, and he certainly

does express a whole day's deer diiving ' as it was

really practised of old ' in eight lines.

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Early Gaelic Book Collections > Blair Collection > Leabhar na Feinne > (35) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/80023899 |

|---|

| Description | A selection of books from a collection of more than 500 titles, mostly on religious and literary topics. Also includes some material dealing with other Celtic languages and societies. Collection created towards the end of the 19th century by Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray. |

|---|

| Description | Selected items from five 'Special and Named Printed Collections'. Includes books in Gaelic and other Celtic languages, works about the Gaels, their languages, literature, culture and history. |

|---|