Blair Collection > Gaelic journal > Volume 1, number 1

(202)

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

igo

THE GAELIC JOURNAL.

considereil ihe feelings and opinions of ignorant Saxons

or ignorant Irishmen, we should have very little respect

for anything really national.

I admit, however, that the points — which in later times

came to be the recognised marks of aspiration —are in

some ways more convenient than the /i's — they are easier to

put in. .ind they shorten the words considerably. But they

have some disadvantages. In the first place, it is very

easy to forget and omit them, both in writing and printing.

Every one familiar with our old writings must have oli-

served how often these points were omitted, and how

difficult it often is on that account to determine the true

pronunciation of words, or to arrive at correct vuks for

aspiration. I do not here mean the writings of the earlier

centuries — say from the sixth to the tenth — when many of

tlie consonants now aspirated were — as I hold — still pro-

nounced pure. I refer more particularly to the writings

of the si.\teenth and seventeenth centuries, in which —

even allowing for much that may not as yet be very well

understood — great carelessness and irregularity in this re-

spect are observable. But/<;/«/i are easily omitted even

by the most careful writers. In the second place, if we

are to consider foreigners, I think ch, g/i, ph, and bh are

more generally intelligible than c, g, p, b— though I ad-

mit that the other aspirated consonants m Irish are not so

simple or so regular in their sounds. But in truth, even

if there were no wrong or unnecessary aspirations in Irish,

and even if the diflerence between Irish and English as to

the frequency of the aspirate were much greater than I be-

lieve it re.illy is, it is not the h or the point (•) that is to

be blamed at all in this matter, but the genius of our lan-

guage — or rather our system of orthography. To any one

curious about our language, half-an-lii "in' ir, :; ;i"'ion

or half an hour's study will furnish li;i;i v M 1 . ; h,

the whole of this part of Irish ]in.iiiii. ,. I in,

thirdly, there is the serious objection il i • ;.-ii)i,

are used in the Roman letter thuTL- aii-r, the n.v.' -iiv l-r

new type. This is the only, or at any ratr. the chiri ob-

jection there can be to what I iiui-l call — with all rc^jiect

to Cljtm Concob^ii\ — the praiseworthy and excellent at-

tempt made first by Father Furlong in his Prayer Book ;

next by Mr. MacPhilpin in the tuam Nnvs; and lately

also by Canon Bourke in some of his works, to popularise

dotted Roman type. If there were any material difierence

between the expensiveness of full Irish type and dotted

Roman, I think much could be said lor the latter.

I have not done yet with Cbann Concoboiip. The mo-

dern Scottish Gael were not the first to use the /; to ex-

press aspiration. It is the faints that are modern — as

used for this purpose at any rate. In the oldest Irish

MSS.— written in what your respected correspondent can-

not blame me for calling old Roman — points were used

only over the j and the /—as often to express the sup-

pression or " eclipsis " of the \ (as in c-f-iiil) as to denote

its aspiration (as in ŵ full), and always to denote the sup-

piesssion of the sound of the p (as in intj pip, now An pip),

though in modern times this sinking of the sound of p has

been strangely referred to the general principle of aspira-

tion. In old Irish, the only consonants .aspirated were

the three tennes c, p, c, and sometimes p and p. But the

aspirate sounds of c p, c were in the earliest times repre-

sented not by points over the letters, but generally by

writing the h after these letters — as some of us venture to

do now in modtrn Roman. For this I need only refer to

any of the more ancient MSS., or to O'Curry's fac-

similes — as also to O'Donovan's Grammar, pp. 41, 42,

and 43. The last-mentioned author on p. 43 of his Irish

Grammar gives — in illustration of this very point, some

monumental inscriptions from the earliest tomb-stones at

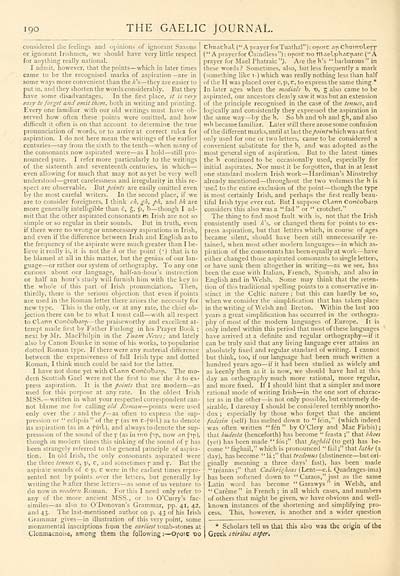

Clonmacnoise, among them the following :— Opoic tio

ChuichoilC'A prayer for Tuathal"): opoic apChuuiTibepp

("Aprayerfor Cuindless"): opoicTJO niielphicpaic (-'A

prayer for Mael Phatraic "). Are the h's " barbarous " in

these words? Sometimes, also, but less frequently a mark

(something like 1-) which was really nothing less than half

of the H was placed over c,p,c, to express the same thing *

In later ages when the vtedials b, t), 5 also came to be

aspirated, our ancestors clearly saw it was but an extension

of the principle recognised in the case of the tenues, and

logically and consistently they expressed the aspiration in

the same way — by the h. So bh and T>h and jh, and also

mil became familiar. Later still there arose some confusion

of the different marks, until at last the/i'/K/which was at first

only used for one or two letters, came to be considered a

convenient substitute for the h, and was adopted as the

most general sign of aspiration. But to the latest times

the h continued to be occasionally used, especially for

initial aspirates. Nor must it be forgotten, that in at least

one standard modern Irish work — Hardiman's Minstrelsy

already mentioned — throughout the two volumes the h is

used to the entire exclusion of the point— though the type

is most certainly Irish, and perhaps the first really beau-

tiful Irish type ever cut. But I suppose clûnn Concobiiiv

considers this also was a "fad" or " crotchet."

The thing to find most fault with is, not that the Irish

consistently used //s. or changed them for points to ex-

press aspiration, but that letters which, in course of ages

became silent, should have been still unnecessarily re-

tained, when most other modern languages — in which as-

pi lation of the consonants has been e(|ually at work — have

either changed those aspirated consonants to single letters,

or have sunk them altogether in writing — as we see, has

been the case with Italian, French, Spanish, and also in

English and in Welsh. Some may think that the reten-

tion of this traditional spelling points to a conservative in-

stinct in the Celtic nature ; but this can hardly be so,

when we consider the simplification that has taken place

in the writing of Welsh and Breton. Within the last 100

years a great simplification has occurred in the orthogra-

phy of most of the modern languages of Europe. It is

only indeed within this period that most of these languages

have arrived at a definite and regular orthography — if it

can be truly said that any living language ever att.ains an

absolutely fixed and regular standard of writing. I cannot

but think, too, if our language had been much written a

hundred years ago — if it had been studied as widely and

as keenly then as it is now, we should have had at this

day an orthography much more rational, more regular,

and more fixed. If I should hint that a simpler and more

rational mode of writing Irish — in the one sort of charac-

ter as in the other — is not only possible, but extremely de-

sirable. I daresay I should be considered terribly unortho-

dox ; especially by those who forget that the ancient

fadesiii (self) has melted down to "fein," (which indeed

was often written "fen" by O'CIery and MacFirbis);

that btidesta (henceforth) has'becnme " feasia ;" that hhoes

(yet) has been made " f(is;" tliat /.?;;/..■// (to get) has be-

come " fághail," which is i.r.nMuiued " f.iil ;" that lathe (a

day), has become "la;" that trcJaiiis (abstinence—but ori-

ginally meaning a three days' fast), has been made

"treanas;" that Cadhri^/ieas [LtViX — e.i. Quadrages-ima)

has been softened down to " Caraos," just as the same

Latin word has become " Garawys " in Welsh, and

"Carême" in French ; in all which cases, and numbers

of others that might be given, we have obvious and well-

known instances of the shortening and simplifying pro-

cess. This, however, is another and a wider question

* Scholars tell us that this also was the origin of the

Greek stiritus asỳer.

THE GAELIC JOURNAL.

considereil ihe feelings and opinions of ignorant Saxons

or ignorant Irishmen, we should have very little respect

for anything really national.

I admit, however, that the points — which in later times

came to be the recognised marks of aspiration —are in

some ways more convenient than the /i's — they are easier to

put in. .ind they shorten the words considerably. But they

have some disadvantages. In the first place, it is very

easy to forget and omit them, both in writing and printing.

Every one familiar with our old writings must have oli-

served how often these points were omitted, and how

difficult it often is on that account to determine the true

pronunciation of words, or to arrive at correct vuks for

aspiration. I do not here mean the writings of the earlier

centuries — say from the sixth to the tenth — when many of

tlie consonants now aspirated were — as I hold — still pro-

nounced pure. I refer more particularly to the writings

of the si.\teenth and seventeenth centuries, in which —

even allowing for much that may not as yet be very well

understood — great carelessness and irregularity in this re-

spect are observable. But/<;/«/i are easily omitted even

by the most careful writers. In the second place, if we

are to consider foreigners, I think ch, g/i, ph, and bh are

more generally intelligible than c, g, p, b— though I ad-

mit that the other aspirated consonants m Irish are not so

simple or so regular in their sounds. But in truth, even

if there were no wrong or unnecessary aspirations in Irish,

and even if the diflerence between Irish and English as to

the frequency of the aspirate were much greater than I be-

lieve it re.illy is, it is not the h or the point (•) that is to

be blamed at all in this matter, but the genius of our lan-

guage — or rather our system of orthography. To any one

curious about our language, half-an-lii "in' ir, :; ;i"'ion

or half an hour's study will furnish li;i;i v M 1 . ; h,

the whole of this part of Irish ]in.iiiii. ,. I in,

thirdly, there is the serious objection il i • ;.-ii)i,

are used in the Roman letter thuTL- aii-r, the n.v.' -iiv l-r

new type. This is the only, or at any ratr. the chiri ob-

jection there can be to what I iiui-l call — with all rc^jiect

to Cljtm Concob^ii\ — the praiseworthy and excellent at-

tempt made first by Father Furlong in his Prayer Book ;

next by Mr. MacPhilpin in the tuam Nnvs; and lately

also by Canon Bourke in some of his works, to popularise

dotted Roman type. If there were any material difierence

between the expensiveness of full Irish type and dotted

Roman, I think much could be said lor the latter.

I have not done yet with Cbann Concoboiip. The mo-

dern Scottish Gael were not the first to use the /; to ex-

press aspiration. It is the faints that are modern — as

used for this purpose at any rate. In the oldest Irish

MSS.— written in what your respected correspondent can-

not blame me for calling old Roman — points were used

only over the j and the /—as often to express the sup-

pression or " eclipsis " of the \ (as in c-f-iiil) as to denote

its aspiration (as in ŵ full), and always to denote the sup-

piesssion of the sound of the p (as in intj pip, now An pip),

though in modern times this sinking of the sound of p has

been strangely referred to the general principle of aspira-

tion. In old Irish, the only consonants .aspirated were

the three tennes c, p, c, and sometimes p and p. But the

aspirate sounds of c p, c were in the earliest times repre-

sented not by points over the letters, but generally by

writing the h after these letters — as some of us venture to

do now in modtrn Roman. For this I need only refer to

any of the more ancient MSS., or to O'Curry's fac-

similes — as also to O'Donovan's Grammar, pp. 41, 42,

and 43. The last-mentioned author on p. 43 of his Irish

Grammar gives — in illustration of this very point, some

monumental inscriptions from the earliest tomb-stones at

Clonmacnoise, among them the following :— Opoic tio

ChuichoilC'A prayer for Tuathal"): opoic apChuuiTibepp

("Aprayerfor Cuindless"): opoicTJO niielphicpaic (-'A

prayer for Mael Phatraic "). Are the h's " barbarous " in

these words? Sometimes, also, but less frequently a mark

(something like 1-) which was really nothing less than half

of the H was placed over c,p,c, to express the same thing *

In later ages when the vtedials b, t), 5 also came to be

aspirated, our ancestors clearly saw it was but an extension

of the principle recognised in the case of the tenues, and

logically and consistently they expressed the aspiration in

the same way — by the h. So bh and T>h and jh, and also

mil became familiar. Later still there arose some confusion

of the different marks, until at last the/i'/K/which was at first

only used for one or two letters, came to be considered a

convenient substitute for the h, and was adopted as the

most general sign of aspiration. But to the latest times

the h continued to be occasionally used, especially for

initial aspirates. Nor must it be forgotten, that in at least

one standard modern Irish work — Hardiman's Minstrelsy

already mentioned — throughout the two volumes the h is

used to the entire exclusion of the point— though the type

is most certainly Irish, and perhaps the first really beau-

tiful Irish type ever cut. But I suppose clûnn Concobiiiv

considers this also was a "fad" or " crotchet."

The thing to find most fault with is, not that the Irish

consistently used //s. or changed them for points to ex-

press aspiration, but that letters which, in course of ages

became silent, should have been still unnecessarily re-

tained, when most other modern languages — in which as-

pi lation of the consonants has been e(|ually at work — have

either changed those aspirated consonants to single letters,

or have sunk them altogether in writing — as we see, has

been the case with Italian, French, Spanish, and also in

English and in Welsh. Some may think that the reten-

tion of this traditional spelling points to a conservative in-

stinct in the Celtic nature ; but this can hardly be so,

when we consider the simplification that has taken place

in the writing of Welsh and Breton. Within the last 100

years a great simplification has occurred in the orthogra-

phy of most of the modern languages of Europe. It is

only indeed within this period that most of these languages

have arrived at a definite and regular orthography — if it

can be truly said that any living language ever att.ains an

absolutely fixed and regular standard of writing. I cannot

but think, too, if our language had been much written a

hundred years ago — if it had been studied as widely and

as keenly then as it is now, we should have had at this

day an orthography much more rational, more regular,

and more fixed. If I should hint that a simpler and more

rational mode of writing Irish — in the one sort of charac-

ter as in the other — is not only possible, but extremely de-

sirable. I daresay I should be considered terribly unortho-

dox ; especially by those who forget that the ancient

fadesiii (self) has melted down to "fein," (which indeed

was often written "fen" by O'CIery and MacFirbis);

that btidesta (henceforth) has'becnme " feasia ;" that hhoes

(yet) has been made " f(is;" tliat /.?;;/..■// (to get) has be-

come " fághail," which is i.r.nMuiued " f.iil ;" that lathe (a

day), has become "la;" that trcJaiiis (abstinence—but ori-

ginally meaning a three days' fast), has been made

"treanas;" that Cadhri^/ieas [LtViX — e.i. Quadrages-ima)

has been softened down to " Caraos," just as the same

Latin word has become " Garawys " in Welsh, and

"Carême" in French ; in all which cases, and numbers

of others that might be given, we have obvious and well-

known instances of the shortening and simplifying pro-

cess. This, however, is another and a wider question

* Scholars tell us that this also was the origin of the

Greek stiritus asỳer.

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Early Gaelic Book Collections > Blair Collection > Gaelic journal > Volume 1, number 1 > (202) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/79315340 |

|---|

| Description | No. 1, Vol. I. November, 1882. |

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | Blair.214 |

| Additional NLS resources: | |

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

| Description | A selection of books from a collection of more than 500 titles, mostly on religious and literary topics. Also includes some material dealing with other Celtic languages and societies. Collection created towards the end of the 19th century by Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray. |

|---|

| Description | Selected items from five 'Special and Named Printed Collections'. Includes books in Gaelic and other Celtic languages, works about the Gaels, their languages, literature, culture and history. |

|---|