Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

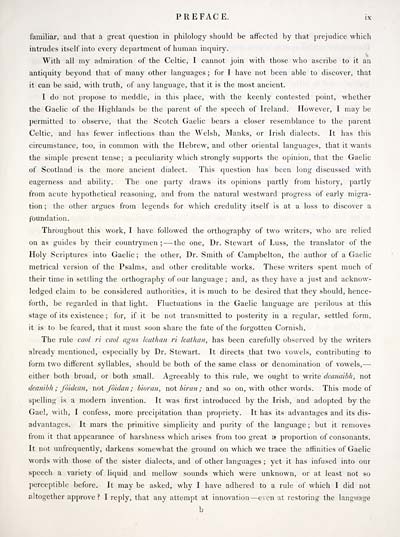

PREFACE. ix

familiar, and that a great question in philology should be affected by that prciudice which

intrudes itself into every department of human inquiry.

With all my admiration of the Celtic, I cannot join with those who ascribe to it an

antiquity beyond that of many other languages ; for I have not been able to discover, that

it can be said, with truth, of any language, that it is the most ancient.

I do not propose to meddle, in this place, with the keenly contested point, whether

the Gaelic of the Highlands be the parent of the speech of Ireland. However, I may be

permitted to observe, that the Scotch Gaelic bears a closer resemblance to the parent

Celtic, and has fewer inflections than the Welsh, Manks, or Irish dialects. It has this

circumstance, too, in common with the Hebrew, and other oriental languages, that it wants

the simple present tense; a peculiarity which strongly supports the opinion, that the Gaelic

of Scotland is the more ancient dialect. This question has been long discussed with

eagerness and ability. The one party draws its opinions partly from history, partly

from acute hypothetical reasoning, and from the natural westward progress of early migra-

tion ; the other argues from legends for which credulity itself is at a loss to discover a

foundation.

Throughout this work, I have followed the orthography of two writers, who are relied

on as guides by their countrymen ; — the one. Dr. Stewart of Luss, the translator of the

Holy Scriptures into Gaelic ; the other, Dr. Smith of Campbelton, the author of a Gaelic

metrical version of the Psalms, and other creditable works. These writers spent much of

their time in settling the orthography of our language; and, as they have a just and acknow-

ledged claim to be considered authorities, it is much to be desired that they should, hence-

forth, be regarded in that light. Fluctuations in the Gaelic language are perilous at this

stage of its existence ; for, if it be not transmitted to posterity in a regular, settled form,

it is to be feared, that it must soon share the fate of the forgotten Cornish.

The rule caol 7-i caol agiis kuthan ri leathan, has been carefully observed by the writers

already mentioned, especially by Dr. Stewart. It directs that two vowels, contributing to

form two different syllables, should be both of the same class or denomination of vowels, —

either both broad, or both small. Agreeably to this rule, we ought to write deanaibh, not

deanibh ; fòkkan, not fòidan ; bioran, not biran; and so on, with other words. This mode of

spelling is a modern invention. It was first introduced by the Irish, and adopted by the

Gael, with, I confess, more precipitation than propriety. It has its advantages and its dis-

advantages. It mars the primitive simplicity and purity of the language ; but it removes

from it that appearance of harshness which arises from too great a proportion of consonants.

It not unfrequently, darkens somewhat the ground on which we trace the affinities of Gaelic

words with those of the sister dialects, and of other languages ; yet it has infused into our

speech a variety of liquid and mellow sounds which were unknown, or at least not so

perceptible before. It may be asked, why I have adhered to a rule of which I did not

altogether approve ? I reply, that any attempt at innovation — even at restoring the language

b

familiar, and that a great question in philology should be affected by that prciudice which

intrudes itself into every department of human inquiry.

With all my admiration of the Celtic, I cannot join with those who ascribe to it an

antiquity beyond that of many other languages ; for I have not been able to discover, that

it can be said, with truth, of any language, that it is the most ancient.

I do not propose to meddle, in this place, with the keenly contested point, whether

the Gaelic of the Highlands be the parent of the speech of Ireland. However, I may be

permitted to observe, that the Scotch Gaelic bears a closer resemblance to the parent

Celtic, and has fewer inflections than the Welsh, Manks, or Irish dialects. It has this

circumstance, too, in common with the Hebrew, and other oriental languages, that it wants

the simple present tense; a peculiarity which strongly supports the opinion, that the Gaelic

of Scotland is the more ancient dialect. This question has been long discussed with

eagerness and ability. The one party draws its opinions partly from history, partly

from acute hypothetical reasoning, and from the natural westward progress of early migra-

tion ; the other argues from legends for which credulity itself is at a loss to discover a

foundation.

Throughout this work, I have followed the orthography of two writers, who are relied

on as guides by their countrymen ; — the one. Dr. Stewart of Luss, the translator of the

Holy Scriptures into Gaelic ; the other, Dr. Smith of Campbelton, the author of a Gaelic

metrical version of the Psalms, and other creditable works. These writers spent much of

their time in settling the orthography of our language; and, as they have a just and acknow-

ledged claim to be considered authorities, it is much to be desired that they should, hence-

forth, be regarded in that light. Fluctuations in the Gaelic language are perilous at this

stage of its existence ; for, if it be not transmitted to posterity in a regular, settled form,

it is to be feared, that it must soon share the fate of the forgotten Cornish.

The rule caol 7-i caol agiis kuthan ri leathan, has been carefully observed by the writers

already mentioned, especially by Dr. Stewart. It directs that two vowels, contributing to

form two different syllables, should be both of the same class or denomination of vowels, —

either both broad, or both small. Agreeably to this rule, we ought to write deanaibh, not

deanibh ; fòkkan, not fòidan ; bioran, not biran; and so on, with other words. This mode of

spelling is a modern invention. It was first introduced by the Irish, and adopted by the

Gael, with, I confess, more precipitation than propriety. It has its advantages and its dis-

advantages. It mars the primitive simplicity and purity of the language ; but it removes

from it that appearance of harshness which arises from too great a proportion of consonants.

It not unfrequently, darkens somewhat the ground on which we trace the affinities of Gaelic

words with those of the sister dialects, and of other languages ; yet it has infused into our

speech a variety of liquid and mellow sounds which were unknown, or at least not so

perceptible before. It may be asked, why I have adhered to a rule of which I did not

altogether approve ? I reply, that any attempt at innovation — even at restoring the language

b

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Early Gaelic Book Collections > Blair Collection > Gaelic dictionary, in two parts > (15) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/79284329 |

|---|

| Description | A selection of books from a collection of more than 500 titles, mostly on religious and literary topics. Also includes some material dealing with other Celtic languages and societies. Collection created towards the end of the 19th century by Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray. |

|---|

| Description | Selected items from five 'Special and Named Printed Collections'. Includes books in Gaelic and other Celtic languages, works about the Gaels, their languages, literature, culture and history. |

|---|