Blair Collection > Celtic magazine > Volume 4

(110)

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

100 THE CELTIC MAGAZINE.

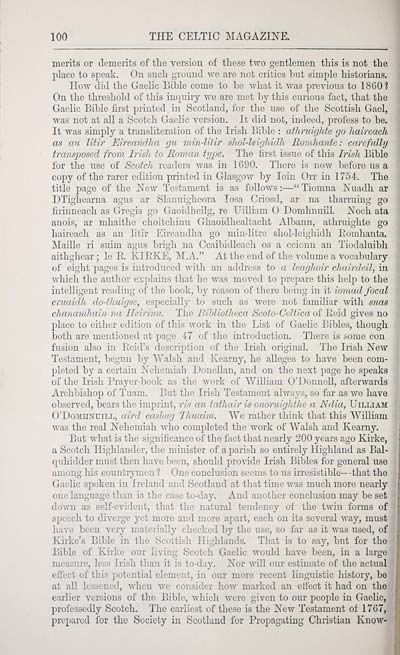

merits or demerits of the version of these two gentlemen this is not the

place to speak. On such ground we are not critics but simple historians.

How did the Gaelic Bible come to be what it was previous to 1860?

On the threshold of this inquiry we are met by this curious fact, that the

Gaelic Bible first printed in Scotland, for the use of the Scottish Gael,

was not at all a Scotch Gaelic version. It did not, indeed, profess to be.

It was simply a traushteration of the Irish Bible : athruighte go haireach

as an litir Eireandha gu min-lilir sliol-leighidli Ronihante: carefully

transposed from Irish to Roman type. The tirst issue of this Irish Bible

for the use of Scotch readers was in 1690. There is now before us a

copy of the rarer edition printed in Glasgow by loin Orr in 1754. The

title page of the 'New Testament is as follows : — " Tiomna E'uadh ar

DTighearna agus ar Slanuigheora losa Criosd, ar na tharruing go

firinneach as Gregis go Gaoidheilg, re Hilliam Domhnuill. Noch ata

anois, ar mhaithe choitchinn Ghaoidhealtacht Albann, athruighte go

haireach as an litir Eireandha go minditre shol-leighidh Eomhanta.

Maillo ri suim agus brigh na Ccaibidleach os a ccionn an Tiodaluibh

aithghear; le E. KIPiKE, M.A." At the end of the volume a vocabulary

of eight pages is introduced with an address to a leaghoir chairdeil, in

■which the author explains that he was moved to prepare this help to the

intelligent reading of the book, by reason of there being in it iomad focal

cr.uaidh do-fhuigse, esjiecially to such as were not familiar with s)i.as

chaaamhain na Ifeirinn. The Bihliotheca Scoto-Celtica of Eeid gives no

place to cither edition of this Avork in the List of Gaelic Bibles, though

both are mentioned at page 47 of the introduction. There is some con

fusion also in Pteid's description of the Irish original. The Irish ISTew

Testament, begun by Walsh and Kearny, he alleges to have been com-

pleted by a certain E"ehemiah Donellan, and on the next page he speaks

of the Irish Prayer-book as the work of William G'Donnell, afterwards

Archbishop of Tuam. But the Irish Testament always, so far as we have

observed, bears the imprint, ris an tathair is onoruightlic a Ndia, Uilliam

O'DoMHNUiLL, aird easing lliuaim. We rather think that this WiUiam

■was the real JSTehemiah who completed the work of AValsh and Kearny.

But what is the significance of the fact that nearly 200 years ago Kirke,

a Scotch Highlander, the minister of a parish so entirely Highland as Bal-

qidudder must then have been, should provide Irish Bibles for general use

among his countrymen 1 One conclusion seems to us irresistible- -that the

Gaelic spoken in Ireland and Scotland at that time was much more nearly

one language than is the case to-day. And another conclusion may be set

down as self-evident, that the natural tendency of the twin forms of

speech to divci'ge yet more and more apart, each on its several way, must

have been very materially checked by the use, so far as it was used, of

Kirke's Bible in the Scottish Highlands. That is to say, but for the

Bible of Kirke our living Scotch Gaelic would have been, in a large

measure, less Irish than it is to-day. Nor wiU our estimate of the actual

oii'ect of this potential element, in our more recent linguistic history, be

at all lessened, when we consider how marked an effect it had on the

earlier versions of the Bible, Avliich were given to our people in Gaelic,

lu'ofessedly Scotch. The earliest of these is the New Testament of 1767,

prepared for the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Know-

merits or demerits of the version of these two gentlemen this is not the

place to speak. On such ground we are not critics but simple historians.

How did the Gaelic Bible come to be what it was previous to 1860?

On the threshold of this inquiry we are met by this curious fact, that the

Gaelic Bible first printed in Scotland, for the use of the Scottish Gael,

was not at all a Scotch Gaelic version. It did not, indeed, profess to be.

It was simply a traushteration of the Irish Bible : athruighte go haireach

as an litir Eireandha gu min-lilir sliol-leighidli Ronihante: carefully

transposed from Irish to Roman type. The tirst issue of this Irish Bible

for the use of Scotch readers was in 1690. There is now before us a

copy of the rarer edition printed in Glasgow by loin Orr in 1754. The

title page of the 'New Testament is as follows : — " Tiomna E'uadh ar

DTighearna agus ar Slanuigheora losa Criosd, ar na tharruing go

firinneach as Gregis go Gaoidheilg, re Hilliam Domhnuill. Noch ata

anois, ar mhaithe choitchinn Ghaoidhealtacht Albann, athruighte go

haireach as an litir Eireandha go minditre shol-leighidh Eomhanta.

Maillo ri suim agus brigh na Ccaibidleach os a ccionn an Tiodaluibh

aithghear; le E. KIPiKE, M.A." At the end of the volume a vocabulary

of eight pages is introduced with an address to a leaghoir chairdeil, in

■which the author explains that he was moved to prepare this help to the

intelligent reading of the book, by reason of there being in it iomad focal

cr.uaidh do-fhuigse, esjiecially to such as were not familiar with s)i.as

chaaamhain na Ifeirinn. The Bihliotheca Scoto-Celtica of Eeid gives no

place to cither edition of this Avork in the List of Gaelic Bibles, though

both are mentioned at page 47 of the introduction. There is some con

fusion also in Pteid's description of the Irish original. The Irish ISTew

Testament, begun by Walsh and Kearny, he alleges to have been com-

pleted by a certain E"ehemiah Donellan, and on the next page he speaks

of the Irish Prayer-book as the work of William G'Donnell, afterwards

Archbishop of Tuam. But the Irish Testament always, so far as we have

observed, bears the imprint, ris an tathair is onoruightlic a Ndia, Uilliam

O'DoMHNUiLL, aird easing lliuaim. We rather think that this WiUiam

■was the real JSTehemiah who completed the work of AValsh and Kearny.

But what is the significance of the fact that nearly 200 years ago Kirke,

a Scotch Highlander, the minister of a parish so entirely Highland as Bal-

qidudder must then have been, should provide Irish Bibles for general use

among his countrymen 1 One conclusion seems to us irresistible- -that the

Gaelic spoken in Ireland and Scotland at that time was much more nearly

one language than is the case to-day. And another conclusion may be set

down as self-evident, that the natural tendency of the twin forms of

speech to divci'ge yet more and more apart, each on its several way, must

have been very materially checked by the use, so far as it was used, of

Kirke's Bible in the Scottish Highlands. That is to say, but for the

Bible of Kirke our living Scotch Gaelic would have been, in a large

measure, less Irish than it is to-day. Nor wiU our estimate of the actual

oii'ect of this potential element, in our more recent linguistic history, be

at all lessened, when we consider how marked an effect it had on the

earlier versions of the Bible, Avliich were given to our people in Gaelic,

lu'ofessedly Scotch. The earliest of these is the New Testament of 1767,

prepared for the Society in Scotland for Propagating Christian Know-

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Early Gaelic Book Collections > Blair Collection > Celtic magazine > Volume 4 > (110) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/76553625 |

|---|

| Description | Volume IV, 1879. |

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | Blair.5 |

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

| Description | A selection of books from a collection of more than 500 titles, mostly on religious and literary topics. Also includes some material dealing with other Celtic languages and societies. Collection created towards the end of the 19th century by Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray. |

|---|

| Description | Selected items from five 'Special and Named Printed Collections'. Includes books in Gaelic and other Celtic languages, works about the Gaels, their languages, literature, culture and history. |

|---|