Blair Collection > Celtic monthly > Volume 1, 1893

(19)

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

THE CELTIC MONTHLY.

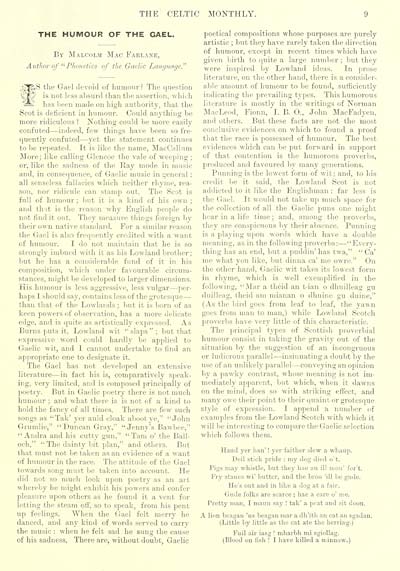

THE HUMOUR OF THE GAEL.

Bv Malcolm Mac Farlane,

Author of " Phonetics of the Gaelic Language."

fiS the Gael devoid of humour] The question

') is not less absurd than the assertion, which

— ' has been made on high authority, that the

Scot is deficient in humour. Could anything be

more ridiculous? Nothing could be more easily

confuted — indeed, few tilings have been so fre-

quently confuted — yet the statement continues

to be repeated. It is like the name, MacCnllnm

More; like calling Glencoe the vale of weeping;

or, like the sadness of the Ray mode in music

and, in consequence, of Gaelic music in general :

all senseless fallacies which neither rhyme, rea

son, nor ridicule can stamp out. The Scot is

full of humour; but it is a kind of his own ;

and that is the reason why English people do

not find it out. They measure things foreign by

their own nati\ e standard. For a similar reason

the Gael is also frequently credited with a want

of humour. I do not maintain that he is so

strongly imbui d with it as his Lowland brother;

but he has a considerable fund of it in his

composition, which under favourable circum-

stances, might be developed to larger dimensions.

Kis humour is less aggressive, less vulgar — per-

haps 1 should say, contains less of the grotesque —

than that of the Lowlands ; but it is born of as

keen powers of observation, has a more delicate

edge, and is quite as artistically expressed. A -,

Burns puts it, Lowland wit "slaps"; but that

expressive word could hardly be applied to

Gaelic wit, and 1 cannot undertake to find an

appropriate one to designate it.

The Gael has not developed an extensive

literature — in fact his is, comparatively speak-

ing, very limited, and is composed principally of

poetry. But in Gaelic poetry there is not much

humour ; and what there is is not of a kind to

hold the fancy of all times. There are few such

songs as "Tak' yer auld cloak aboot ye," "John

Grumlie," " Duncan Gray." "Jenny's Bawbee,"

" Andra and his cutty gun," ''Tarn o' the Ball-

och," " The dainty bit plan," and others. Bui

that must not lie taken as an evidence of a want

of humour in the race. The attitude of the I lael

towards song must be taken into account, lie

did not so much look upon poetry as an ai t

whereby lie might exhibit his powers and confer

pleasure upon others as he found it a vent for

letting the steam off, so to speak, from his pent

up feelings. When the Gael felt merry he

danced, and any kind of words served to carry

the music : when he felt sad he sung the cause

of his sadness. There are, without doubt, Gaelic

poetical compositions whose purposes are purely

artistic ; but they have rarely taken the direction

of humour, except in recent times which have

given birth to quite a large number; but they

were inspired by Lowland ideas. In prose

literature, on the other hand, there is a consider-

able amount of humour to be found, sufficiently

indicating the prevailing types. This humorous

literature is mostly in the writings of Norman

Mael d, Fionn, I. B. O., John MacFadyen,

and others. But these facts are not the most

conclusive evidences on which to found a proof

that the race is possessed of humour. The best

evidences which can be put forward in support

of that contention is the humorous proverbs,

produced and favoured by many generations.

Punning is the lowest form of wit; and. to his

credit be it said, the Lowland Scot is not

addieied to it like the Englishman: far less is

the Gael. It would not take up much space for

the collection of all the Gaelic puns one mighl

hear in a life time ; and, among the proverbs,

they are conspicuous by their absence. Punning

is a playing upon words which have a double

meaning, as in the following proverbs: — "Every-

thing has an end, but a puddin' has twa," " Ca'

me what you like, but dinna ca' me owre." On

the other hand, Gaelic wit takes its lowest form

in rhyme, which is well exemplified in the

follow in-. "Mar a theid an t-ian o dhuilleag gu

duilleag, t In id am mianan o dhuine gu duinc,"

( As the bird goes from leaf to leaf, the yawn

goes from man to man,) while Lowland Scotch

have very little of this characteristic.

The principal types of Scottish proverbial

humour consist in taking the v.ra\ it y out of the

situation by the suggestion of an incongruous

or ludicrous parallel — insinuating a doubt by the

use of an unlikely parallel -conveying an opinion

by a pawky contrast, whose meaning is not im-

mediately apparent, but which, when it dawns

on the mind, does so with striking effect, and

many owe their point to their quaint or grotesque

style of expression. I append a number of

examples from the Lowland Scotch with which it

will lie interesting to compare the ( laelic selection

which follows them.

Hand yer liau' ! yer faither slew a wliaup.

Deil stick pride : my dog died o't.

I'ii:- may whistle, but they liae an ill mou' for't.

Fry stanes wi' butter, and the broo 'ill lie gude.

He's out aud in like a dog at a fair.

Guile folks are scarce : hae a care o' me.

Pretty man, I maim say ! tak' a peat and sit doon.

A lion beagan 'us beagan mar a dh'ith an eat an sgadan.

(Little by little as the cat ate the herring.)

Fuil air iasg ' mharhh mi sgiollag.

(Blood on risli ! I have killed a minnow.)

THE HUMOUR OF THE GAEL.

Bv Malcolm Mac Farlane,

Author of " Phonetics of the Gaelic Language."

fiS the Gael devoid of humour] The question

') is not less absurd than the assertion, which

— ' has been made on high authority, that the

Scot is deficient in humour. Could anything be

more ridiculous? Nothing could be more easily

confuted — indeed, few tilings have been so fre-

quently confuted — yet the statement continues

to be repeated. It is like the name, MacCnllnm

More; like calling Glencoe the vale of weeping;

or, like the sadness of the Ray mode in music

and, in consequence, of Gaelic music in general :

all senseless fallacies which neither rhyme, rea

son, nor ridicule can stamp out. The Scot is

full of humour; but it is a kind of his own ;

and that is the reason why English people do

not find it out. They measure things foreign by

their own nati\ e standard. For a similar reason

the Gael is also frequently credited with a want

of humour. I do not maintain that he is so

strongly imbui d with it as his Lowland brother;

but he has a considerable fund of it in his

composition, which under favourable circum-

stances, might be developed to larger dimensions.

Kis humour is less aggressive, less vulgar — per-

haps 1 should say, contains less of the grotesque —

than that of the Lowlands ; but it is born of as

keen powers of observation, has a more delicate

edge, and is quite as artistically expressed. A -,

Burns puts it, Lowland wit "slaps"; but that

expressive word could hardly be applied to

Gaelic wit, and 1 cannot undertake to find an

appropriate one to designate it.

The Gael has not developed an extensive

literature — in fact his is, comparatively speak-

ing, very limited, and is composed principally of

poetry. But in Gaelic poetry there is not much

humour ; and what there is is not of a kind to

hold the fancy of all times. There are few such

songs as "Tak' yer auld cloak aboot ye," "John

Grumlie," " Duncan Gray." "Jenny's Bawbee,"

" Andra and his cutty gun," ''Tarn o' the Ball-

och," " The dainty bit plan," and others. Bui

that must not lie taken as an evidence of a want

of humour in the race. The attitude of the I lael

towards song must be taken into account, lie

did not so much look upon poetry as an ai t

whereby lie might exhibit his powers and confer

pleasure upon others as he found it a vent for

letting the steam off, so to speak, from his pent

up feelings. When the Gael felt merry he

danced, and any kind of words served to carry

the music : when he felt sad he sung the cause

of his sadness. There are, without doubt, Gaelic

poetical compositions whose purposes are purely

artistic ; but they have rarely taken the direction

of humour, except in recent times which have

given birth to quite a large number; but they

were inspired by Lowland ideas. In prose

literature, on the other hand, there is a consider-

able amount of humour to be found, sufficiently

indicating the prevailing types. This humorous

literature is mostly in the writings of Norman

Mael d, Fionn, I. B. O., John MacFadyen,

and others. But these facts are not the most

conclusive evidences on which to found a proof

that the race is possessed of humour. The best

evidences which can be put forward in support

of that contention is the humorous proverbs,

produced and favoured by many generations.

Punning is the lowest form of wit; and. to his

credit be it said, the Lowland Scot is not

addieied to it like the Englishman: far less is

the Gael. It would not take up much space for

the collection of all the Gaelic puns one mighl

hear in a life time ; and, among the proverbs,

they are conspicuous by their absence. Punning

is a playing upon words which have a double

meaning, as in the following proverbs: — "Every-

thing has an end, but a puddin' has twa," " Ca'

me what you like, but dinna ca' me owre." On

the other hand, Gaelic wit takes its lowest form

in rhyme, which is well exemplified in the

follow in-. "Mar a theid an t-ian o dhuilleag gu

duilleag, t In id am mianan o dhuine gu duinc,"

( As the bird goes from leaf to leaf, the yawn

goes from man to man,) while Lowland Scotch

have very little of this characteristic.

The principal types of Scottish proverbial

humour consist in taking the v.ra\ it y out of the

situation by the suggestion of an incongruous

or ludicrous parallel — insinuating a doubt by the

use of an unlikely parallel -conveying an opinion

by a pawky contrast, whose meaning is not im-

mediately apparent, but which, when it dawns

on the mind, does so with striking effect, and

many owe their point to their quaint or grotesque

style of expression. I append a number of

examples from the Lowland Scotch with which it

will lie interesting to compare the ( laelic selection

which follows them.

Hand yer liau' ! yer faither slew a wliaup.

Deil stick pride : my dog died o't.

I'ii:- may whistle, but they liae an ill mou' for't.

Fry stanes wi' butter, and the broo 'ill lie gude.

He's out aud in like a dog at a fair.

Guile folks are scarce : hae a care o' me.

Pretty man, I maim say ! tak' a peat and sit doon.

A lion beagan 'us beagan mar a dh'ith an eat an sgadan.

(Little by little as the cat ate the herring.)

Fuil air iasg ' mharhh mi sgiollag.

(Blood on risli ! I have killed a minnow.)

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Early Gaelic Book Collections > Blair Collection > Celtic monthly > Volume 1, 1893 > (19) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/75841596 |

|---|

| Description | Vol. I. |

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | Blair.54 |

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

| Description | A selection of books from a collection of more than 500 titles, mostly on religious and literary topics. Also includes some material dealing with other Celtic languages and societies. Collection created towards the end of the 19th century by Lady Evelyn Stewart Murray. |

|---|

| Description | Selected items from five 'Special and Named Printed Collections'. Includes books in Gaelic and other Celtic languages, works about the Gaels, their languages, literature, culture and history. |

|---|