Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

i a jam a^jfi

which several generations of chil-

dren have heartily enjoyed for its

stories without bestowing a thought

on its philosophy, was born in Well-

close Square in 1748.

His father held a place in the

Custom House, and left him a for-

tune of £1,200 a year. He was edu-

cated at the Charterhouse and

Oxford, and spent some time in

France, where he received the new

philosophy of education.

Having resolved on marriage, he

determined that his wife should he

modelled in accordance with the

new light.

He therefore went to an orphan

asylum at Shrewsbury and picked

out a flaxen-haired girl of twelve,

whom he named Sabrina Sidney,

after the Severn and Algernon

Sidney, and then to the Foundling

Hospital in London, where he

selected a second, whom he called

Lucretia.

In taking these girls he gave a

written pledge that within a year

he would place one of them with a

respectable tradesman, giving £100

to bind her apprentice, and that he

should maintain her if she should

turn out well until she married or

commenced business, in either of

which cases he would advance £500.

With Sabrina and Lucretia he set

off for France, in order that in quiet

he might discover and discipline

their characters. He, however,

quarrelled with the girls.

Next day they took smallpox, and

he had to nurse them night and day,

and by-and-by he was glad to return

to London and get Lucretia off his

hands by apprenticing her to a

milliner on Ludgate Hill. She be-

haved well, and on her marriage

to a substantial linendraper, Day

cheerfully produced his promised

dowry of £500.

Poor Sabrina could by no means

qualify for Mr. Day. Against the

sense of pain and danger no disci-

pline could fortify her. When Day

dropped melting sealing-wax on her

arms, she flinched, and when he

fired pistols at ber garments, she

started and screamed. When he

told her secrets, she divulged

them.

He packed her off to an ordinary

boarding school, kept her there for

three years, allowed her £50 a year,

gave her £500 on her marriage to a

barrister, and when she became a

widow, with two boys, he pensioned

her with £30 a year.

In 1788 he married Miss Milnes, of

Wakefield, a lady whose opinions

coincided with his own.

DUTCH NAMES FOR THE

MONTHS.

In Holland the following poetic

names for the months are in use:—

January — Lauromaand, chilly

month ; February — Svrokelmaand,

vegetation month ; March — Lent-

maand, spring month ; April— Gras-

maand, grass month; May — Blow-

maand, flower month ; June—Zomer-

maand, summer month; July—Hooy-

maand, hay month; August — Oost-

maand, harvest month ; September—

Hertsmaand, autumn month ; October

— Wynmaand,wine month; November

—Slagmaand, slaughter month; De-

cember— Winter maand, winter month.

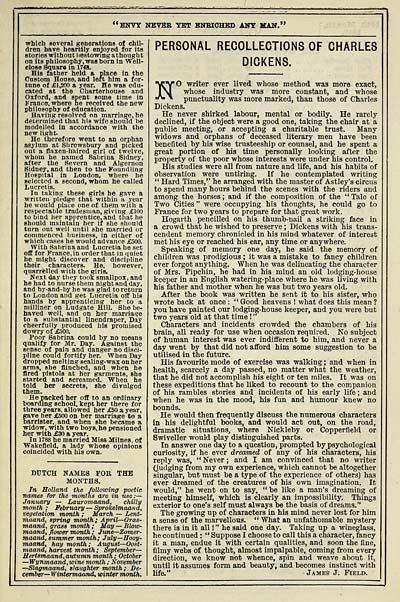

PERSONAL RECOLLECTIONS OF CHARLES

DICKENS.

WFfO writer ever lived whose method was more exact,

J[M whose industry was more constant, and whose

" ^ punctuality was more marked, than those of Charles

Dickens.

He never shirked labour, mental or bodily. He rarely

declined, if the object were a good one, taking the chair at a

public meeting, or accepting a charitable trust. Many

widows and orphans of deceased literary men have been

benefited by his wise trusteeship or counsel, and he spent a

great portion of his time personally looking after the

property of the poor whose interests were under his control.

His studies were all from nature and life, and his habits of

Observation were untiring. If he contemplated writing

" Hard Times," he arranged with the master of Astley's circus

to spend many hours behind the scenes with the riders and

among the horses ; and if the composition of the " Tale of

Two Cities " were occupying his thoughts, he could go to

France for two years to prepare for that great work.

Hogarth pencilled on his thumb-nail a striking face in

a crowd that he wished to preserve ; Dickens with his trans-

cendent memory chronicled in his mind whatever of interest

met his eye or reached his ear, any time or anywhere.

Speaking of memory one day, he said the memory of

children was prodigious ; it was a mistake to fancy children

ever forgot anything. When he was delineating the character

of Mrs. Pipchin, he had in his mind an old lodging-house

keeper in an English watering-place where he was living with

his father and mother when he was but two years old.

After the book was written he sent it to his sister, who

wrote back at once : " Good heavens ! what does this mean ?

you have painted our lodging-house keeper, and you were but

two years old at that time 1 "

Characters and incidents crowded the chambers of his

brain, all ready for use when occasion required. No subject

of human interest was ever indifferent to him, and never a

day went by that did not afford him some suggestion to be

utilised in the future.

His favourite mode of exercise was walking ; and when in

health, scarcely a day passed, no matter what the weather,

that he did not accomplish his eight or ten miles. It was on

these expeditions that he liked to recount to the companion

of his rambles stories and incidents of his early life ; and

when he was in the mood, his fun and humour knew no

bounds.

He would then frequently discuss the numerous characters

in his delightful books, and would act out, on the road,

dramatic situations, where Nickleby or Copperfield or

Swiveller would play distinguished parts.

In answer one day to a question, prompted by psychological

curiosity, if he ever dreamed of any of his characters, his

reply was, " Never ; and I am convinced that no writer

(judging from my own experience, which cannot be altogether

singular, but must be a type of the experience of others) has

ever dreamed of the creatures of his own imagination. It

would," he went on to say, "be like a man's dreaming of

meeting himself, which is clearly an impossibility. Things

exterior to one's self must always be the basis of dreams."

The growing up of characters in his mind never lost for him

a sense of the marvellous. " What an unfathomable mystery

there is in it all 1 " he said one day. Taking up a wineglass,

he continued : " Suppose I choose to call this a character, fancy

it a man, endue it with certain qualities, and soon the fine,

filmy webs of thought, almost impalpable, coming from every

direction, we know not whence, spin and weave about it,

until it assumes form and beauty, and becomes instinct with

life." James J. Field.

which several generations of chil-

dren have heartily enjoyed for its

stories without bestowing a thought

on its philosophy, was born in Well-

close Square in 1748.

His father held a place in the

Custom House, and left him a for-

tune of £1,200 a year. He was edu-

cated at the Charterhouse and

Oxford, and spent some time in

France, where he received the new

philosophy of education.

Having resolved on marriage, he

determined that his wife should he

modelled in accordance with the

new light.

He therefore went to an orphan

asylum at Shrewsbury and picked

out a flaxen-haired girl of twelve,

whom he named Sabrina Sidney,

after the Severn and Algernon

Sidney, and then to the Foundling

Hospital in London, where he

selected a second, whom he called

Lucretia.

In taking these girls he gave a

written pledge that within a year

he would place one of them with a

respectable tradesman, giving £100

to bind her apprentice, and that he

should maintain her if she should

turn out well until she married or

commenced business, in either of

which cases he would advance £500.

With Sabrina and Lucretia he set

off for France, in order that in quiet

he might discover and discipline

their characters. He, however,

quarrelled with the girls.

Next day they took smallpox, and

he had to nurse them night and day,

and by-and-by he was glad to return

to London and get Lucretia off his

hands by apprenticing her to a

milliner on Ludgate Hill. She be-

haved well, and on her marriage

to a substantial linendraper, Day

cheerfully produced his promised

dowry of £500.

Poor Sabrina could by no means

qualify for Mr. Day. Against the

sense of pain and danger no disci-

pline could fortify her. When Day

dropped melting sealing-wax on her

arms, she flinched, and when he

fired pistols at ber garments, she

started and screamed. When he

told her secrets, she divulged

them.

He packed her off to an ordinary

boarding school, kept her there for

three years, allowed her £50 a year,

gave her £500 on her marriage to a

barrister, and when she became a

widow, with two boys, he pensioned

her with £30 a year.

In 1788 he married Miss Milnes, of

Wakefield, a lady whose opinions

coincided with his own.

DUTCH NAMES FOR THE

MONTHS.

In Holland the following poetic

names for the months are in use:—

January — Lauromaand, chilly

month ; February — Svrokelmaand,

vegetation month ; March — Lent-

maand, spring month ; April— Gras-

maand, grass month; May — Blow-

maand, flower month ; June—Zomer-

maand, summer month; July—Hooy-

maand, hay month; August — Oost-

maand, harvest month ; September—

Hertsmaand, autumn month ; October

— Wynmaand,wine month; November

—Slagmaand, slaughter month; De-

cember— Winter maand, winter month.

PERSONAL RECOLLECTIONS OF CHARLES

DICKENS.

WFfO writer ever lived whose method was more exact,

J[M whose industry was more constant, and whose

" ^ punctuality was more marked, than those of Charles

Dickens.

He never shirked labour, mental or bodily. He rarely

declined, if the object were a good one, taking the chair at a

public meeting, or accepting a charitable trust. Many

widows and orphans of deceased literary men have been

benefited by his wise trusteeship or counsel, and he spent a

great portion of his time personally looking after the

property of the poor whose interests were under his control.

His studies were all from nature and life, and his habits of

Observation were untiring. If he contemplated writing

" Hard Times," he arranged with the master of Astley's circus

to spend many hours behind the scenes with the riders and

among the horses ; and if the composition of the " Tale of

Two Cities " were occupying his thoughts, he could go to

France for two years to prepare for that great work.

Hogarth pencilled on his thumb-nail a striking face in

a crowd that he wished to preserve ; Dickens with his trans-

cendent memory chronicled in his mind whatever of interest

met his eye or reached his ear, any time or anywhere.

Speaking of memory one day, he said the memory of

children was prodigious ; it was a mistake to fancy children

ever forgot anything. When he was delineating the character

of Mrs. Pipchin, he had in his mind an old lodging-house

keeper in an English watering-place where he was living with

his father and mother when he was but two years old.

After the book was written he sent it to his sister, who

wrote back at once : " Good heavens ! what does this mean ?

you have painted our lodging-house keeper, and you were but

two years old at that time 1 "

Characters and incidents crowded the chambers of his

brain, all ready for use when occasion required. No subject

of human interest was ever indifferent to him, and never a

day went by that did not afford him some suggestion to be

utilised in the future.

His favourite mode of exercise was walking ; and when in

health, scarcely a day passed, no matter what the weather,

that he did not accomplish his eight or ten miles. It was on

these expeditions that he liked to recount to the companion

of his rambles stories and incidents of his early life ; and

when he was in the mood, his fun and humour knew no

bounds.

He would then frequently discuss the numerous characters

in his delightful books, and would act out, on the road,

dramatic situations, where Nickleby or Copperfield or

Swiveller would play distinguished parts.

In answer one day to a question, prompted by psychological

curiosity, if he ever dreamed of any of his characters, his

reply was, " Never ; and I am convinced that no writer

(judging from my own experience, which cannot be altogether

singular, but must be a type of the experience of others) has

ever dreamed of the creatures of his own imagination. It

would," he went on to say, "be like a man's dreaming of

meeting himself, which is clearly an impossibility. Things

exterior to one's self must always be the basis of dreams."

The growing up of characters in his mind never lost for him

a sense of the marvellous. " What an unfathomable mystery

there is in it all 1 " he said one day. Taking up a wineglass,

he continued : " Suppose I choose to call this a character, fancy

it a man, endue it with certain qualities, and soon the fine,

filmy webs of thought, almost impalpable, coming from every

direction, we know not whence, spin and weave about it,

until it assumes form and beauty, and becomes instinct with

life." James J. Field.

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Scottish Post Office Directories > Towns > Stirling > Cook and Wylie's Stirling Directory > 1897 > (29) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/85022228 |

|---|

| Description | Directories of individual Scottish towns and their suburbs. |

|---|

| Description | Around 700 Scottish directories published annually by the Post Office or private publishers between 1773 and 1911. Most of Scotland covered, with a focus on Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen. Most volumes include a general directory (A-Z by surname), street directory (A-Z by street) and trade directory (A-Z by trade). |

|---|