An Comunn Gàidhealach Publications > Gaidheal > Volumes 44--45, January 1949--December 1950

(423) Page 91

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

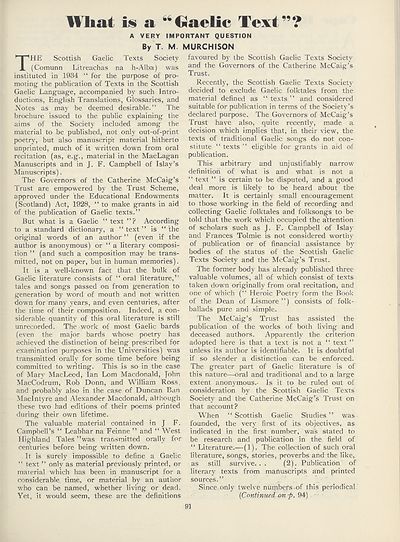

What is a Gaelic Text”?

A VERY IMPORTANT QUESTION

By T. M MURCHISON

THE Scottish Gaelic Texts Society

(Comunn Litreachas na h-Alba) was

instituted in 1934 “ for the purpose of pro¬

moting the publication of Texts in the Scottish

Gaelic Language, accompanied by such Intro¬

ductions, English Translations, Glossaries, and

Notes as may be deemed desirable.” The

brochure issued to the public explaining the

aims of the Society included among the

material to be published, not only out-of-print

poetry, but also manuscript material hitherto

unprinted, much of it written down from oral

recitation (as, e.g., material in the MacLagan

Manuscripts and in J. F. Campbell of Islay’s

Manuscripts).

The Governors of the Catherine McCaig’s

Trust are empowered by the Trust Scheme,

approved under the Educational Endowments

(Scotland) Act, 1928, ‘‘ to make grants in aid

of the publication of Gaelic texts.”

But what is a Gaelic “ text ”? According

to a standard dictionary, a “ text ” is “ the

original words of an author” (even if the

author is anonymous) or ‘‘ a literary composi¬

tion ” (and such a composition may be trans¬

mitted, not on paper, but in human memories).

It is a well-known fact that the bulk of

Gaelic literature consists of ” oral literature,”

tales and songs passed on from generation to

generation by word of mouth and not written

down for many years, and even centuries, after

the time of their composition. Indeed, a con¬

siderable quantity of this oral literature is still

unrecorded. The work of most Gaelic bards

(even the major bards whose poetry has

achieved the distinction of being prescribed fpr

examination purposes in the Universities) was

transmitted orally for some time before being

committed to writing. This is so in the case

of Mary MacLeod, Ian Lorn Macdonald, John

MacCodrum, Rob Donn, and William Ross,

and probably also in the case of Duncan Ban

MacIntyre and Alexander Macdonald, although

these two had editions of their poems printed

during their own lifetime.

The valuable material contained in J F.

Campbell’s “ Leabhar na Feinne ” and “ West

Highland Tales ’’was transmitted orally for

cen'turies before being written down.

It is surely impossible to define a Gaelic

“ text ” only as material previously printed, or

material which has been in manuscript for a

considerable time, or material by an author

who can be named, whether living or dead.

Yet, it would seem, these are the definitions

favoured by the Scottish Gaelic Texts Society

and the Governors of the Catherine McCaig’s

Trust.

Recently, the Scottish Gaelic Texts Society

decided to exclude Gaelic folktales from the

material defined as ” texts ” and considered

suitable for publication in terms of the Society’s

declared purpose. The Governors of McCaig’s

Trust have also, quite recently, made a

decision which implies that, in their view, the

texts of traditional Gaelic songs do not con¬

stitute “ texts ” eligible for grants in aid of

publication.

This arbitrary and unjustifiably narrow

definition of what is and what is not a

” text ” is certain to be disputed, and a good

deal more is likely to be heard about the

matter. It is certainly small encouragement

to those working in the field of recording and

collecting Gaelic folktales and folksongs to be

told that the work which occupied the attention

of scholars such as J. F. Campbell of Islay

and Frances Tolmie is not considered worthy

of publication or of financial assistance by

bodies of the status of the Scottish Gaelic

Texts Society and the McCaig’s Trust.

The former body has already published three

valuable volumes, all of which consist of texts

taken down originally from oral recitation, and

one of which (‘‘ Heroic Poetry form the Book

of the Dean of Lismore ”) consists of folk-

ballads pure and simple.

The McCaig’s Trust has assisted the

publication of the works of both living and

deceased authors. Apparently the criterion

adopted here is that a text is not a “ text ”

unless its author is identifiable. It is doubtful

if so slender a distinction can be enforced.

The greater part of Gaelic literature is of

this nature—oral and traditional and to a large

extent anonymous.- Is it to be ruled out of

consideration by the Scottish Gaelic Texts

Society and the Catherine McCaig’s Trust on

that account?

When “ Scottish Gaelic Studies ” was

founded, the very first of its objectives, as

indicated in the first number, was stated to

be research and publication in the field of

” Literature.—(1). The collection of such oral

literature, songs, stories, proverbs and the like,

as still survive. . . (2). Publication of

literary texts from manuscripts and printed

sources.”

Since only twelve numbers-of this periodical

{Continued an -p. 94)

A VERY IMPORTANT QUESTION

By T. M MURCHISON

THE Scottish Gaelic Texts Society

(Comunn Litreachas na h-Alba) was

instituted in 1934 “ for the purpose of pro¬

moting the publication of Texts in the Scottish

Gaelic Language, accompanied by such Intro¬

ductions, English Translations, Glossaries, and

Notes as may be deemed desirable.” The

brochure issued to the public explaining the

aims of the Society included among the

material to be published, not only out-of-print

poetry, but also manuscript material hitherto

unprinted, much of it written down from oral

recitation (as, e.g., material in the MacLagan

Manuscripts and in J. F. Campbell of Islay’s

Manuscripts).

The Governors of the Catherine McCaig’s

Trust are empowered by the Trust Scheme,

approved under the Educational Endowments

(Scotland) Act, 1928, ‘‘ to make grants in aid

of the publication of Gaelic texts.”

But what is a Gaelic “ text ”? According

to a standard dictionary, a “ text ” is “ the

original words of an author” (even if the

author is anonymous) or ‘‘ a literary composi¬

tion ” (and such a composition may be trans¬

mitted, not on paper, but in human memories).

It is a well-known fact that the bulk of

Gaelic literature consists of ” oral literature,”

tales and songs passed on from generation to

generation by word of mouth and not written

down for many years, and even centuries, after

the time of their composition. Indeed, a con¬

siderable quantity of this oral literature is still

unrecorded. The work of most Gaelic bards

(even the major bards whose poetry has

achieved the distinction of being prescribed fpr

examination purposes in the Universities) was

transmitted orally for some time before being

committed to writing. This is so in the case

of Mary MacLeod, Ian Lorn Macdonald, John

MacCodrum, Rob Donn, and William Ross,

and probably also in the case of Duncan Ban

MacIntyre and Alexander Macdonald, although

these two had editions of their poems printed

during their own lifetime.

The valuable material contained in J F.

Campbell’s “ Leabhar na Feinne ” and “ West

Highland Tales ’’was transmitted orally for

cen'turies before being written down.

It is surely impossible to define a Gaelic

“ text ” only as material previously printed, or

material which has been in manuscript for a

considerable time, or material by an author

who can be named, whether living or dead.

Yet, it would seem, these are the definitions

favoured by the Scottish Gaelic Texts Society

and the Governors of the Catherine McCaig’s

Trust.

Recently, the Scottish Gaelic Texts Society

decided to exclude Gaelic folktales from the

material defined as ” texts ” and considered

suitable for publication in terms of the Society’s

declared purpose. The Governors of McCaig’s

Trust have also, quite recently, made a

decision which implies that, in their view, the

texts of traditional Gaelic songs do not con¬

stitute “ texts ” eligible for grants in aid of

publication.

This arbitrary and unjustifiably narrow

definition of what is and what is not a

” text ” is certain to be disputed, and a good

deal more is likely to be heard about the

matter. It is certainly small encouragement

to those working in the field of recording and

collecting Gaelic folktales and folksongs to be

told that the work which occupied the attention

of scholars such as J. F. Campbell of Islay

and Frances Tolmie is not considered worthy

of publication or of financial assistance by

bodies of the status of the Scottish Gaelic

Texts Society and the McCaig’s Trust.

The former body has already published three

valuable volumes, all of which consist of texts

taken down originally from oral recitation, and

one of which (‘‘ Heroic Poetry form the Book

of the Dean of Lismore ”) consists of folk-

ballads pure and simple.

The McCaig’s Trust has assisted the

publication of the works of both living and

deceased authors. Apparently the criterion

adopted here is that a text is not a “ text ”

unless its author is identifiable. It is doubtful

if so slender a distinction can be enforced.

The greater part of Gaelic literature is of

this nature—oral and traditional and to a large

extent anonymous.- Is it to be ruled out of

consideration by the Scottish Gaelic Texts

Society and the Catherine McCaig’s Trust on

that account?

When “ Scottish Gaelic Studies ” was

founded, the very first of its objectives, as

indicated in the first number, was stated to

be research and publication in the field of

” Literature.—(1). The collection of such oral

literature, songs, stories, proverbs and the like,

as still survive. . . (2). Publication of

literary texts from manuscripts and printed

sources.”

Since only twelve numbers-of this periodical

{Continued an -p. 94)

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

| An Comunn Gàidhealach > An Comunn Gàidhealach Publications > Gaidheal > Volumes 44--45, January 1949--December 1950 > (423) Page 91 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/127127112 |

|---|

| Description | This contains items published by An Comunn, which are not specifically Mòd-related. It includes journals, annual reports and corporate documents, policy statements, educational resources and published plays and literature. It is arranged alphabetically by title. |

|---|

| Description | A collection of over 400 items published by An Comunn Gàidhealach, the organisation which promotes Gaelic language and culture and organises the Royal National Mòd. Dating from 1891 up to the present day, the collection includes journals and newspapers, annual reports, educational materials, national Mòd programmes, published Mòd literature and music. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|