Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

36

AN GAIDHEAL.

An Dnbhlachd, 1947.

THOUGHTS FOR STUDENTS OF CELTIC ART.

By Augusta Lamoht.

We have travelled far from the artistic standpoint of the

long ago when the early Celts took delight in decoration by

means of purely abstract or geometric forms of ornament.

So much is this the case that in these modern days it is diffi¬

cult to get away from the idea that pictorial art is art j>ar

excellence, and that decoration must necessarily consist in

depicting some known object or representing the forms of

Nature.

How familiar to us all are the little boxes ornamented by a

view or a horse’s head, the notion that Scotland must be

symbolised by a terrier dog or a representation of the bagpipes !

How inevitable is the idea that scenes, human forms, birds

or flowers must necessarily form the basis of decorative design !

Not that the use of natural forms in decoration is in all cases

to be deprecated, but, when it goes to such lengths as to indicate

that a draughtsman is imitative because he has no originality

of idea, it does go to show that his outlook is poles apart from

that of the Celtic craftsman of olden times whose imaginative

thought found expression in the limitless variety of abstract

design.

The first step, then, in the appreciation of Celtic Art

is to acquire insight into the characteristics of abstract or

geometric art in general of which the Celtic is a special develop¬

ment.

This leads quickly to the second point which it is essential

to grasp. The Celts had no monopoly of this abstract form of

art: other peoples made use of it too, but the Celts developed

it in so special and characteristic a way as to make it peculiarly

their own. One of their characteristics was to retain balance

and rhythm while avoiding uniformity. If, then, you come

across a border of interlace repeating endlessly the same

pattern with dreary monotony, or an over-all key-pattem

on an extended surface making the eye long for something

plain on which to rest—these mere patterns are far from being

Celtic in conception. The border of interlace would be broken

up here and there by some pleasing variety in design ; the key-

pattem would be used to fill up some small space requiring

ornamentation, and not made to cover a large area having the

effect of wearying the eye. Interlace work, scroll or key

patterns, zoomorphic designs and so forth are not in them¬

selves Celtic, but they were adapted by the Celts with the

characteristic taste and imagination which gave a special

impress to their artistic work.

Where the Celts signally failed was when they turned aside

from their natural bent of abstract art and attempted figure

drawing. The style of the figures in the Book of Kells is held

to be due to Byzantine influence, and it seems therefore that

the old illuminators, instead of allowing free scope to their

own exuberant fancy for decorative design, became in this

respect mere imitators. It is not desirable that we should

become imitators at second-hand, and present-day students

would do well to avoid attempting to incorporate in their

work figures in this style, merely because examples happen to

occur in a Celtic manuscript. Those who wish to combine

Celtic ornament with figures, or to illustrate a Celtic theme in

appropriate style, could not do better than consider how

successfully the former aim has been attained by the late

Mr. John Duncan in his window in Paisley Abbey, and the

latter by Miss Helen Lamb in her beautiful little illuminated

panel of Saint Columba recently exhibited in Glasgow.

Another important point for the student to bear in mind

is the relation of the design to the material on which it is to be

executed. The intricate and minutely detailed designs of the

old manuscripts were executed with pen and brush on vellum,

and are quite inappropriate for application to textiles by means

of needle and thread. Generally speaking, the coarser the

material the simpler and bolder should the pattern be. How¬

ever skilfully executed a complicated pattern may be, the

effect is not pleasing if it is applied to some unsuitable material.

The craftsman of the Ardagh Chalice doubtless felt his work to

be a kind of worship—no time, no skill, no trouble were to be

spared in ornamenting an object of supreme and lasting

importance ; even the under side of its base had to be made as

beautiful as the parts which meet the eye. But for lesser

things less elaboration is necessary. Ornamentation applied

with restraint produces a more satisfying effect than laborious

intricacies when these are out of proportion to the importance

of the object ornamented or to the length of time it is likely

to last.

Let us consider also the relation of ornament to the object

to be ornamented, especially in the case of pottery, wood¬

carving or metal work. In the first place, such objects must

themselves be of good design, otherwise no amount of decora¬

tion will serve to beautify them. Given a well-designed object

consider secondly : does it require decoration at all ? Imagine,

for instance, the case of a jug of pleasing form; shape and

colour may be quite sufficient to satisfy the eye, and the

application of ornament may merely produce the effect of

fussiness, distracting attention from a graceful outline. The

craft-worker must therefore be careful always in the first

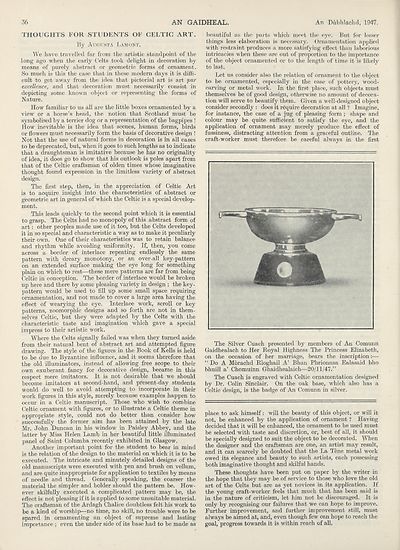

The Silver Cuach presented by members of An Comunn

Gaidhealach to Her Royal Highness The Princess Elizabeth,

on the occasion of her marriage, bears the inscription:—

“ Do A Morachd Rioghail A’ Bhan Phrionnsa Ealasaid bho

bhuill a’ Chomuinn Ghaidhealaich—20/11/47.”

The Cuaeh is engraved with Celtic ornamentation designed

by Dr. Colin Sinclair. On the oak base, which also has a

Celtic design, is the badge of An Comunn in silver.

place to ask himself: will the beauty of this object, or will it

not, be enhanced by the application of ornament ? Having

decided that it will be enhanced, the ornament to be used must

be selected with taste and discretion, or, best of all, it should

be specially designed to suit the object to be decorated. When

the designer and the craftsman are one, an artist may result,

and it can scarcely be doubted that the La Tfene metal work

owed its elegance and beauty to such artists, each possessing

both imaginative thought and skilful hands.

These thoughts have been put on paper by the writer in

the hope that they may be of service to those who love the old

art of the Celts but are as yet novices in its application. If

the young craft-worker feels that much that has been said is

in the nature of criticism, let him not be discouraged. It is

only by recognising our failures that we can hope to improve.

Further improvement, and further improvement still, must

always be aimed at, and, even though few can hope to reach the

goal, progress towards it is within reach of all.

AN GAIDHEAL.

An Dnbhlachd, 1947.

THOUGHTS FOR STUDENTS OF CELTIC ART.

By Augusta Lamoht.

We have travelled far from the artistic standpoint of the

long ago when the early Celts took delight in decoration by

means of purely abstract or geometric forms of ornament.

So much is this the case that in these modern days it is diffi¬

cult to get away from the idea that pictorial art is art j>ar

excellence, and that decoration must necessarily consist in

depicting some known object or representing the forms of

Nature.

How familiar to us all are the little boxes ornamented by a

view or a horse’s head, the notion that Scotland must be

symbolised by a terrier dog or a representation of the bagpipes !

How inevitable is the idea that scenes, human forms, birds

or flowers must necessarily form the basis of decorative design !

Not that the use of natural forms in decoration is in all cases

to be deprecated, but, when it goes to such lengths as to indicate

that a draughtsman is imitative because he has no originality

of idea, it does go to show that his outlook is poles apart from

that of the Celtic craftsman of olden times whose imaginative

thought found expression in the limitless variety of abstract

design.

The first step, then, in the appreciation of Celtic Art

is to acquire insight into the characteristics of abstract or

geometric art in general of which the Celtic is a special develop¬

ment.

This leads quickly to the second point which it is essential

to grasp. The Celts had no monopoly of this abstract form of

art: other peoples made use of it too, but the Celts developed

it in so special and characteristic a way as to make it peculiarly

their own. One of their characteristics was to retain balance

and rhythm while avoiding uniformity. If, then, you come

across a border of interlace repeating endlessly the same

pattern with dreary monotony, or an over-all key-pattem

on an extended surface making the eye long for something

plain on which to rest—these mere patterns are far from being

Celtic in conception. The border of interlace would be broken

up here and there by some pleasing variety in design ; the key-

pattem would be used to fill up some small space requiring

ornamentation, and not made to cover a large area having the

effect of wearying the eye. Interlace work, scroll or key

patterns, zoomorphic designs and so forth are not in them¬

selves Celtic, but they were adapted by the Celts with the

characteristic taste and imagination which gave a special

impress to their artistic work.

Where the Celts signally failed was when they turned aside

from their natural bent of abstract art and attempted figure

drawing. The style of the figures in the Book of Kells is held

to be due to Byzantine influence, and it seems therefore that

the old illuminators, instead of allowing free scope to their

own exuberant fancy for decorative design, became in this

respect mere imitators. It is not desirable that we should

become imitators at second-hand, and present-day students

would do well to avoid attempting to incorporate in their

work figures in this style, merely because examples happen to

occur in a Celtic manuscript. Those who wish to combine

Celtic ornament with figures, or to illustrate a Celtic theme in

appropriate style, could not do better than consider how

successfully the former aim has been attained by the late

Mr. John Duncan in his window in Paisley Abbey, and the

latter by Miss Helen Lamb in her beautiful little illuminated

panel of Saint Columba recently exhibited in Glasgow.

Another important point for the student to bear in mind

is the relation of the design to the material on which it is to be

executed. The intricate and minutely detailed designs of the

old manuscripts were executed with pen and brush on vellum,

and are quite inappropriate for application to textiles by means

of needle and thread. Generally speaking, the coarser the

material the simpler and bolder should the pattern be. How¬

ever skilfully executed a complicated pattern may be, the

effect is not pleasing if it is applied to some unsuitable material.

The craftsman of the Ardagh Chalice doubtless felt his work to

be a kind of worship—no time, no skill, no trouble were to be

spared in ornamenting an object of supreme and lasting

importance ; even the under side of its base had to be made as

beautiful as the parts which meet the eye. But for lesser

things less elaboration is necessary. Ornamentation applied

with restraint produces a more satisfying effect than laborious

intricacies when these are out of proportion to the importance

of the object ornamented or to the length of time it is likely

to last.

Let us consider also the relation of ornament to the object

to be ornamented, especially in the case of pottery, wood¬

carving or metal work. In the first place, such objects must

themselves be of good design, otherwise no amount of decora¬

tion will serve to beautify them. Given a well-designed object

consider secondly : does it require decoration at all ? Imagine,

for instance, the case of a jug of pleasing form; shape and

colour may be quite sufficient to satisfy the eye, and the

application of ornament may merely produce the effect of

fussiness, distracting attention from a graceful outline. The

craft-worker must therefore be careful always in the first

The Silver Cuach presented by members of An Comunn

Gaidhealach to Her Royal Highness The Princess Elizabeth,

on the occasion of her marriage, bears the inscription:—

“ Do A Morachd Rioghail A’ Bhan Phrionnsa Ealasaid bho

bhuill a’ Chomuinn Ghaidhealaich—20/11/47.”

The Cuaeh is engraved with Celtic ornamentation designed

by Dr. Colin Sinclair. On the oak base, which also has a

Celtic design, is the badge of An Comunn in silver.

place to ask himself: will the beauty of this object, or will it

not, be enhanced by the application of ornament ? Having

decided that it will be enhanced, the ornament to be used must

be selected with taste and discretion, or, best of all, it should

be specially designed to suit the object to be decorated. When

the designer and the craftsman are one, an artist may result,

and it can scarcely be doubted that the La Tfene metal work

owed its elegance and beauty to such artists, each possessing

both imaginative thought and skilful hands.

These thoughts have been put on paper by the writer in

the hope that they may be of service to those who love the old

art of the Celts but are as yet novices in its application. If

the young craft-worker feels that much that has been said is

in the nature of criticism, let him not be discouraged. It is

only by recognising our failures that we can hope to improve.

Further improvement, and further improvement still, must

always be aimed at, and, even though few can hope to reach the

goal, progress towards it is within reach of all.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

| An Comunn Gàidhealach > An Comunn Gàidhealach Publications > Gaidheal > Volume 43, October 1947--December 1948 > (44) Page 36 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/125251800 |

|---|

| Description | This contains items published by An Comunn, which are not specifically Mòd-related. It includes journals, annual reports and corporate documents, policy statements, educational resources and published plays and literature. It is arranged alphabetically by title. |

|---|

| Description | A collection of over 400 items published by An Comunn Gàidhealach, the organisation which promotes Gaelic language and culture and organises the Royal National Mòd. Dating from 1891 up to the present day, the collection includes journals and newspapers, annual reports, educational materials, national Mòd programmes, published Mòd literature and music. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|