Glen Collection of printed music > Printed music > British minstrel, and musical and literary miscellany

(748) Page 56 - Young who in wisdom

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

56

THE BRITISH MINSTREL; AND

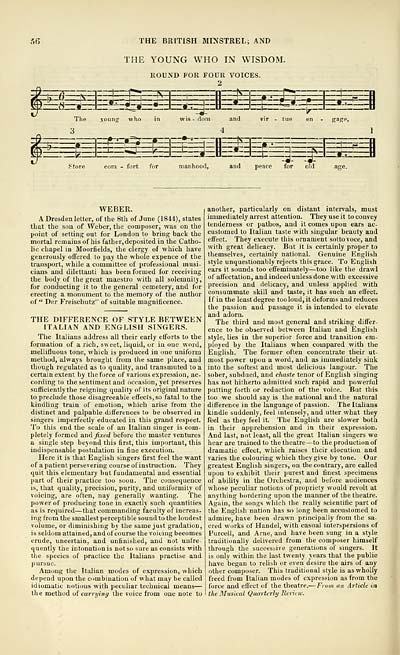

THE YOUNG WHO IN WISDOM.

ROUND FOR FOUR VOICES.

2

^^^^

I

5s;

The young who in wis - dom

and

vir - tue en

3

iig^

— , — m-i —

^-

tF=^

==i=:

zwr^

:s:

Store

com - fort for manhood, and peace for old

•Jizr

gaRe,

age.

I

WEBER.

A Dresden letter, of the 8th of June (1844), states

that the son of Weber, the composer, was on the

point of setting out for London to bring back the

mortal remains of his father, deposited in the Catho-

lic chapel in Moorfields, the clergy of which have

generously offered to pay the whole expence of the

transport, while a committee of professional musi-

cians and dilettanti has been formed for receiving

the body of the great maestro with all solemnity,

for conducting it to the general cemetery, and for

erecting a monument to the memory of the author

of " Der Freischutz" of suitable magnificence.

THE DIFFERENCE OF STYLE BETWEEN

ITALIAN AND ENGLISH SINGERS.

The Italians address all their early efforts to the

formation of a rich, sweet, liquid, or in one word,

mellifluous tone, which is produced in one uniform

method, always brought from the same place, and

though regulated as to quality, and transmuted to a

certain extent by the force of various expression, ac-

cording to the sentiment and occasion, yet preserves

sufficiently the reigning quality of its original nature

to preclude those disagreeable effects, so fatal to the

kindling train of emotion, which arise from the

distinct and palpable differences to be observed in

singers imperfectly educated in this grand respect.

To this end the scale of an Italian singer is com-

pletely formed aod fixed before the master ventures

a single step beyond this first, this important, this

indispensable postulation in fine execution.

Here it is that English singers first feel the want

of a patient persevering course of instruction. They

quit this elementary but fundamental and essential

part of their practice too soon. The consequence

is, that quality, precision, purity, and uniformity of

voicing, are often, nay generally wanting. The

power of producing tone in exactly such quantities

as is required — that commanding faculty of increas-

ing from the smallest perceptible sound to the loudest

volume, or diminishing by the same just gradation,

is seldom attained, and of course the voicing becomes

crude, uncertain, and unfinished, and not uufre-

quently the intonation is not so sure as consists with

the species of practice the Italians practise and

pursue.

Among the Italian modes of expression, which

depend upon the combination of what may be called

idiomatic notions with peculiar technical means —

the method uf carrying the voice from one note to

another, particularly on distant intervals, must

immediately arrest attention. They use it to convey

tenderness or pathos, and it comes upon ears ac-

customed to Italian taste with singular beauty and

effect. They execute this ornament sotto voce, and

with great delicacy. But it is certainly proper to

themselves, certainly national. Genuine English

style unquestionably rejects this grace. To English

ears it sounds too effeminately — too like the drawl

of affectation, and indeedunless done with excessive

precision and delicacy, and unless applied with

consummate skill and taste, it has such an effect.

If in the least degree too loud, it deforms and reduces

the passion and passage it is intended to elevate

and adorn.

The third and most general and striking differ-

ence to be observed between Italian and English

style, lies in the superior force and transition em-

ployed by the Italians when compared with the

English. The former often concentrate their ut-

most power upon a word, and as immediately sink

into the softest and most delicious langour. The

sober, subdued, and chaste tenor of English singing

has not hitherto admitted such rapid and powerful

putting forth or reduction of the voice. But this

too we should say is the national and the natural

difference in the language of passion. The Italians

kindle suddenly, feel intensely, and utter what they

fbel as they feel it. The English are slower both

in their apprehension and in their expression.

And last, not least, all the great Italian singers we

hear are trained to the theatre — to the production of

dramatic effect, which raises their elocution and

varies the colouring which they give by tone. Our

greatest English singers, on the contrary, are called

upon to exhibit their purest and finest specimens

of ability in the Orchestra, and before audiences

whose peculiar notions of propriety would revolt at

anything bordering upon the manner of the theatre.

Again, the songs which the really scientific part of

the English nation has so long been accustomed to

admire, have been drawn principally from the sa-

cred works of Handel, with casual interspersions of

Purcell, and Arne, and have been sung in a style

traditionally delivered from the composer himself

through the successive generations of singers. It

is only within the last twenty years that the public

have began to relish or even desire the airs of any

other composer. This traditional style is as wholly

freed from Italian modes of expression as from the

force and efl'ect of the theatre. — From an Article in

the Musical Quarterly Renew.

THE BRITISH MINSTREL; AND

THE YOUNG WHO IN WISDOM.

ROUND FOR FOUR VOICES.

2

^^^^

I

5s;

The young who in wis - dom

and

vir - tue en

3

iig^

— , — m-i —

^-

tF=^

==i=:

zwr^

:s:

Store

com - fort for manhood, and peace for old

•Jizr

gaRe,

age.

I

WEBER.

A Dresden letter, of the 8th of June (1844), states

that the son of Weber, the composer, was on the

point of setting out for London to bring back the

mortal remains of his father, deposited in the Catho-

lic chapel in Moorfields, the clergy of which have

generously offered to pay the whole expence of the

transport, while a committee of professional musi-

cians and dilettanti has been formed for receiving

the body of the great maestro with all solemnity,

for conducting it to the general cemetery, and for

erecting a monument to the memory of the author

of " Der Freischutz" of suitable magnificence.

THE DIFFERENCE OF STYLE BETWEEN

ITALIAN AND ENGLISH SINGERS.

The Italians address all their early efforts to the

formation of a rich, sweet, liquid, or in one word,

mellifluous tone, which is produced in one uniform

method, always brought from the same place, and

though regulated as to quality, and transmuted to a

certain extent by the force of various expression, ac-

cording to the sentiment and occasion, yet preserves

sufficiently the reigning quality of its original nature

to preclude those disagreeable effects, so fatal to the

kindling train of emotion, which arise from the

distinct and palpable differences to be observed in

singers imperfectly educated in this grand respect.

To this end the scale of an Italian singer is com-

pletely formed aod fixed before the master ventures

a single step beyond this first, this important, this

indispensable postulation in fine execution.

Here it is that English singers first feel the want

of a patient persevering course of instruction. They

quit this elementary but fundamental and essential

part of their practice too soon. The consequence

is, that quality, precision, purity, and uniformity of

voicing, are often, nay generally wanting. The

power of producing tone in exactly such quantities

as is required — that commanding faculty of increas-

ing from the smallest perceptible sound to the loudest

volume, or diminishing by the same just gradation,

is seldom attained, and of course the voicing becomes

crude, uncertain, and unfinished, and not uufre-

quently the intonation is not so sure as consists with

the species of practice the Italians practise and

pursue.

Among the Italian modes of expression, which

depend upon the combination of what may be called

idiomatic notions with peculiar technical means —

the method uf carrying the voice from one note to

another, particularly on distant intervals, must

immediately arrest attention. They use it to convey

tenderness or pathos, and it comes upon ears ac-

customed to Italian taste with singular beauty and

effect. They execute this ornament sotto voce, and

with great delicacy. But it is certainly proper to

themselves, certainly national. Genuine English

style unquestionably rejects this grace. To English

ears it sounds too effeminately — too like the drawl

of affectation, and indeedunless done with excessive

precision and delicacy, and unless applied with

consummate skill and taste, it has such an effect.

If in the least degree too loud, it deforms and reduces

the passion and passage it is intended to elevate

and adorn.

The third and most general and striking differ-

ence to be observed between Italian and English

style, lies in the superior force and transition em-

ployed by the Italians when compared with the

English. The former often concentrate their ut-

most power upon a word, and as immediately sink

into the softest and most delicious langour. The

sober, subdued, and chaste tenor of English singing

has not hitherto admitted such rapid and powerful

putting forth or reduction of the voice. But this

too we should say is the national and the natural

difference in the language of passion. The Italians

kindle suddenly, feel intensely, and utter what they

fbel as they feel it. The English are slower both

in their apprehension and in their expression.

And last, not least, all the great Italian singers we

hear are trained to the theatre — to the production of

dramatic effect, which raises their elocution and

varies the colouring which they give by tone. Our

greatest English singers, on the contrary, are called

upon to exhibit their purest and finest specimens

of ability in the Orchestra, and before audiences

whose peculiar notions of propriety would revolt at

anything bordering upon the manner of the theatre.

Again, the songs which the really scientific part of

the English nation has so long been accustomed to

admire, have been drawn principally from the sa-

cred works of Handel, with casual interspersions of

Purcell, and Arne, and have been sung in a style

traditionally delivered from the composer himself

through the successive generations of singers. It

is only within the last twenty years that the public

have began to relish or even desire the airs of any

other composer. This traditional style is as wholly

freed from Italian modes of expression as from the

force and efl'ect of the theatre. — From an Article in

the Musical Quarterly Renew.

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Special collections of printed music > Glen Collection of printed music > Printed music > British minstrel, and musical and literary miscellany > (748) Page 56 - Young who in wisdom |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/91443921 |

|---|

| Description | Scottish songs and music of the 18th and early 19th centuries, including music for the Highland bagpipe. These are selected items from the collection of John Glen (1833 to 1904). Also includes a few manuscripts, some treatises, and other books on the subject. |

|---|

| Description | The Glen Collection and the Inglis Collection represent mainly 18th and 19th century Scottish music, including Scottish songs. The collections of Berlioz and Verdi collected by bibliographer Cecil Hopkinson contain contemporary and later editions of the works of the two composers Berlioz and Verdi. |

|---|