Series 1 > Statutes of the Scottish Church, 1225-1559

(151) Page 30

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

SO STATUTES OF THE SCOTTISH CHURCH

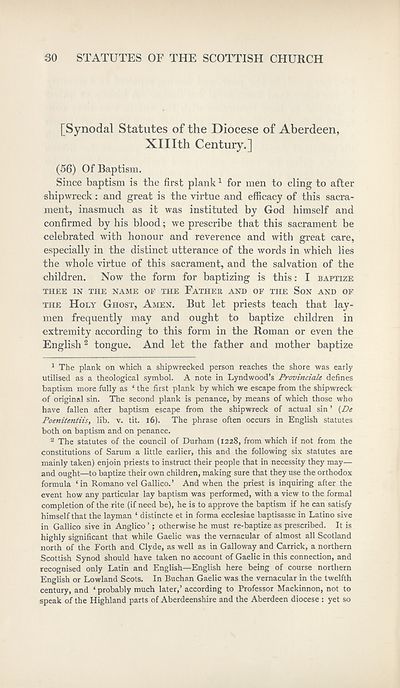

[Synodal Statutes of the Diocese of Aberdeen,

Xlllth Century.]

(56) Of Baptism.

Since baptism is the first plank1 for men to cling to after

shipwreck: and great is the virtue and efficacy of this sacra¬

ment, inasmuch as it was instituted by God himself and

confirmed by his blood; we prescribe that this sacrament be

celebrated with honour and reverence and with great care,

especially in the distinct utterance of the words in which lies

the whole virtue of this sacrament, and the salvation of the

children. Now the form for baptizing is this: I baptize

THEE IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER AND OF THE SON AND OF

the Holy Ghost, Amen. But let priests teach that lay¬

men frequently may and ought to baptize children in

extremity according to this form in the Roman or even the

English2 tongue. And let the father and mother baptize

1 The plank on which a shipwrecked person reaches the shore was early

utilised as a theological symbol. A note in Lyndwood’s Provincials defines

baptism more fully as ‘ the first plank by which we escape from the shipwreck

of original sin. The second plank is penance, by means of which those who

have fallen after baptism escape from the shipwreck of actual sin ’ {De

Poenitentiis, lib. v. tit. l6). The phrase often occurs in English statutes

both on baptism and on penance.

2 The statutes of the council of Durham (1228, from which if not from the

constitutions of Sarum a little earlier, this and the following six statutes are

mainly taken) enjoin priests to instruct their people that in necessity they may—

and ought—to baptize their own children, making sure that they use the orthodox

formula ‘ in Romano vel Gallico.’ And when the priest is inquiring after the

event how any particular lay baptism was performed, with a view to the formal

completion of the rite (if need be), he is to approve the baptism if he can satisfy

himself that the layman ‘ distincte et in forma ecclesiae baptisasse in Latino sive

in Gallico sive in Anglico ’; otherwise he must re-baptize as prescribed. It is

highly significant that while Gaelic was the vernacular of almost all Scotland

north of the Forth and Clyde, as well as in Galloway and Carrick, a northern

Scottish Synod should have taken no account of Gaelic in this connection, and

recognised only Latin and English—English here being of course northern

English or Lowland Scots. In Buchan Gaelic was the vernacular in the twelfth

century, and ‘ probably much later,’ according to Professor Mackinnon, not to

speak of the Highland parts of Aberdeenshire and the Aberdeen diocese : yet so

[Synodal Statutes of the Diocese of Aberdeen,

Xlllth Century.]

(56) Of Baptism.

Since baptism is the first plank1 for men to cling to after

shipwreck: and great is the virtue and efficacy of this sacra¬

ment, inasmuch as it was instituted by God himself and

confirmed by his blood; we prescribe that this sacrament be

celebrated with honour and reverence and with great care,

especially in the distinct utterance of the words in which lies

the whole virtue of this sacrament, and the salvation of the

children. Now the form for baptizing is this: I baptize

THEE IN THE NAME OF THE FATHER AND OF THE SON AND OF

the Holy Ghost, Amen. But let priests teach that lay¬

men frequently may and ought to baptize children in

extremity according to this form in the Roman or even the

English2 tongue. And let the father and mother baptize

1 The plank on which a shipwrecked person reaches the shore was early

utilised as a theological symbol. A note in Lyndwood’s Provincials defines

baptism more fully as ‘ the first plank by which we escape from the shipwreck

of original sin. The second plank is penance, by means of which those who

have fallen after baptism escape from the shipwreck of actual sin ’ {De

Poenitentiis, lib. v. tit. l6). The phrase often occurs in English statutes

both on baptism and on penance.

2 The statutes of the council of Durham (1228, from which if not from the

constitutions of Sarum a little earlier, this and the following six statutes are

mainly taken) enjoin priests to instruct their people that in necessity they may—

and ought—to baptize their own children, making sure that they use the orthodox

formula ‘ in Romano vel Gallico.’ And when the priest is inquiring after the

event how any particular lay baptism was performed, with a view to the formal

completion of the rite (if need be), he is to approve the baptism if he can satisfy

himself that the layman ‘ distincte et in forma ecclesiae baptisasse in Latino sive

in Gallico sive in Anglico ’; otherwise he must re-baptize as prescribed. It is

highly significant that while Gaelic was the vernacular of almost all Scotland

north of the Forth and Clyde, as well as in Galloway and Carrick, a northern

Scottish Synod should have taken no account of Gaelic in this connection, and

recognised only Latin and English—English here being of course northern

English or Lowland Scots. In Buchan Gaelic was the vernacular in the twelfth

century, and ‘ probably much later,’ according to Professor Mackinnon, not to

speak of the Highland parts of Aberdeenshire and the Aberdeen diocese : yet so

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Scottish History Society volumes > Series 1 > Statutes of the Scottish Church, 1225-1559 > (151) Page 30 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/126918798 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|

| Description | Over 180 volumes, published by the Scottish History Society, containing original sources on Scotland's history and people. With a wide range of subjects, the books collectively cover all periods from the 12th to 20th centuries, and reflect changing trends in Scottish history. Sources are accompanied by scholarly interpretation, references and bibliographies. Volumes are usually published annually, and more digitised volumes will be added as they become available. |

|---|