Collected works > Edinburgh edition, 1894-98 - Works of Robert Louis Stevenson > Volume 28, 1898 - Appendix

(34) Page 14

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

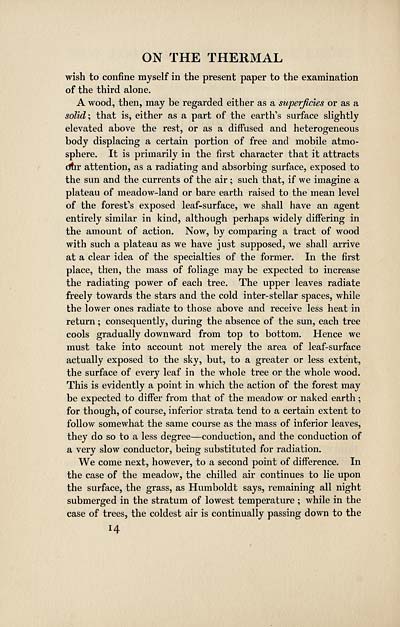

ON THE THERMAL

wish to confine myself in the present paper to the examination

of the third alone.

A wood, then, may be regarded either as a superficies or as a

solid; that is, either as a part of the earth's surface slightly

elevated above the rest, or as a diffused and heterogeneous

body displacing a certain portion of free and mobile atmo-

sphere. It is primarily in the first character that it attracts

dtir attention, as a radiating and absorbing surface, exposed to

the sun and the currents of the air ; such that, if we imagine a

plateau of meadow-land or bare earth raised to the mean level

of the forest's exposed leaf-surface, we shall have an agent

entirely similar in kind, although perhaps widely differing in

the amount of action. Now, by comparing a tract of wood

with such a plateau as we have just supposed, we shall arrive

at a clear idea of the specialties of the former. In the first

place, then, the mass of foliage may be expected to increase

the radiating power of each tree. The upper leaves radiate

freely towards the stars and the cold inter-stellar spaces, while

the lower ones radiate to those above and receive less heat in

return ; consequently, during the absence of the sun, each tree

cools gradually downward from top to bottom. Hence we

must take into account not merely the area of leaf-surface

actually exposed to the sky, but, to a greater or less extent,

the surface of every leaf in the whole tree or the whole wood.

This is evidently a point in which the action of the forest may

be expected to differ from that of the meadow or naked earth ;

for though, of course, inferior strata tend to a certain extent to

follow somewhat the same course as the mass of inferior leaves,

they do so to a less degree — conduction, and the conduction of

a very slow conductor, being substituted for radiation.

We come next, however, to a second point of difference. In

the case of the meadow, the chilled air continues to lie upon

the surface, the grass, as Humboldt says, remaining all night

submerged in the stratum of lowest temperature ; while in the

case of trees, the coldest air is continually passing down to the

14

wish to confine myself in the present paper to the examination

of the third alone.

A wood, then, may be regarded either as a superficies or as a

solid; that is, either as a part of the earth's surface slightly

elevated above the rest, or as a diffused and heterogeneous

body displacing a certain portion of free and mobile atmo-

sphere. It is primarily in the first character that it attracts

dtir attention, as a radiating and absorbing surface, exposed to

the sun and the currents of the air ; such that, if we imagine a

plateau of meadow-land or bare earth raised to the mean level

of the forest's exposed leaf-surface, we shall have an agent

entirely similar in kind, although perhaps widely differing in

the amount of action. Now, by comparing a tract of wood

with such a plateau as we have just supposed, we shall arrive

at a clear idea of the specialties of the former. In the first

place, then, the mass of foliage may be expected to increase

the radiating power of each tree. The upper leaves radiate

freely towards the stars and the cold inter-stellar spaces, while

the lower ones radiate to those above and receive less heat in

return ; consequently, during the absence of the sun, each tree

cools gradually downward from top to bottom. Hence we

must take into account not merely the area of leaf-surface

actually exposed to the sky, but, to a greater or less extent,

the surface of every leaf in the whole tree or the whole wood.

This is evidently a point in which the action of the forest may

be expected to differ from that of the meadow or naked earth ;

for though, of course, inferior strata tend to a certain extent to

follow somewhat the same course as the mass of inferior leaves,

they do so to a less degree — conduction, and the conduction of

a very slow conductor, being substituted for radiation.

We come next, however, to a second point of difference. In

the case of the meadow, the chilled air continues to lie upon

the surface, the grass, as Humboldt says, remaining all night

submerged in the stratum of lowest temperature ; while in the

case of trees, the coldest air is continually passing down to the

14

Set display mode to: Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Early editions of Robert Louis Stevenson > Collected works > Works of Robert Louis Stevenson > Appendix > (34) Page 14 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/99383720 |

|---|

| Form / genre: |

Written and printed matter > Books |

|---|---|

| Dates / events: |

1898 [Date published] |

| Places: |

Europe >

United Kingdom >

Scotland >

Edinburgh >

Edinburgh

(inhabited place) [Place printed] |

| Subject / content: |

Essays Anthologies |

| Person / organisation: |

Colvin, Sidney, 1845-1927 [Author of introduction, etc.] |

| Form / genre: |

Written and printed matter > Books |

|---|---|

| Dates / events: |

1894-1898 [Date printed] |

| Places: |

Europe >

United Kingdom >

Scotland >

Edinburgh >

Edinburgh

(inhabited place) [Place printed] |

| Subject / content: |

Collected works |

| Person / organisation: |

Chatto & Windus (Firm) [Distributor] Stevenson, Robert Louis, 1850-1894 [Author] T. and A. Constable [Printer] Longmans, Green, and Co. [Publisher] Colvin, Sidney, 1845-1927 [Editor] |

| Person / organisation: |

Stevenson, Robert Louis, 1850-1894 [Author] |

|---|