The ‘Narrative’

Originally published in 1845 in Boston and going through multiple revised editions in 1845 and 1846 in Ireland and Britain, ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave’, is the first autobiography of Frederick Douglass. This inspirational work is widely renowned and critically acclaimed as the canonical autobiographical work within 19th century African American and US literary histories.

That said, the only way in which to do justice to Douglass’s lifelong re-creation of his public and private senses of selfhood is to read his ‘Narrative’ not as a definitive or representative work but as one among many works authored by hundreds of formerly enslaved and self-emancipated writers living across the Atlantic world, many of whom came to Scotland on antislavery speaking tours. Among Douglass’s contemporaries, countless self-emancipated authors turned activists were equally responsible for publishing autobiographies of equally extraordinary political, social, historical, and artistic power.

The autobiographies written by Douglass, and the many other formerly enslaved individuals that have been handed down to us, are the stories of the survivors who made it to freedom. It is only when we remember that these are the testimonies of those who escaped that we can begin to come to grips with the traumatising reality that the vast majority of the millions of women, children, and men who were bought and sold lived and died in slavery.

As Douglass himself was painfully aware, nothing is to be gained and everything is to be lost by reading him as the only representative enslaved liberator and his 'Narrative' as the representative autobiography. At our peril do we focus on Douglass’s ‘story of the slave’ to the exclusion of all others. To the day he died, Douglass’s realisation regarding his lifelong failure to do justice to those who lived and died in slavery, many of them his family members and friends, in print, song, oratory or political activism, was a source of devastating emotional pain that afflicted his entire life.

A prolific and inspirational writer no less than a trailblazing reformer, Douglass held steadfast to his rights as an author, orator, and philosopher. His vast bodies of literary, philosophical, and political works not only include multiple autobiographies and written accounts of his speeches but also a novella, poetry, historical and philosophical essays, political tracts, travel diaries, and private and public correspondence. For Douglass, his 'Narrative' was in no way definitive regarding his credentials as an author and activist.

The Portrait

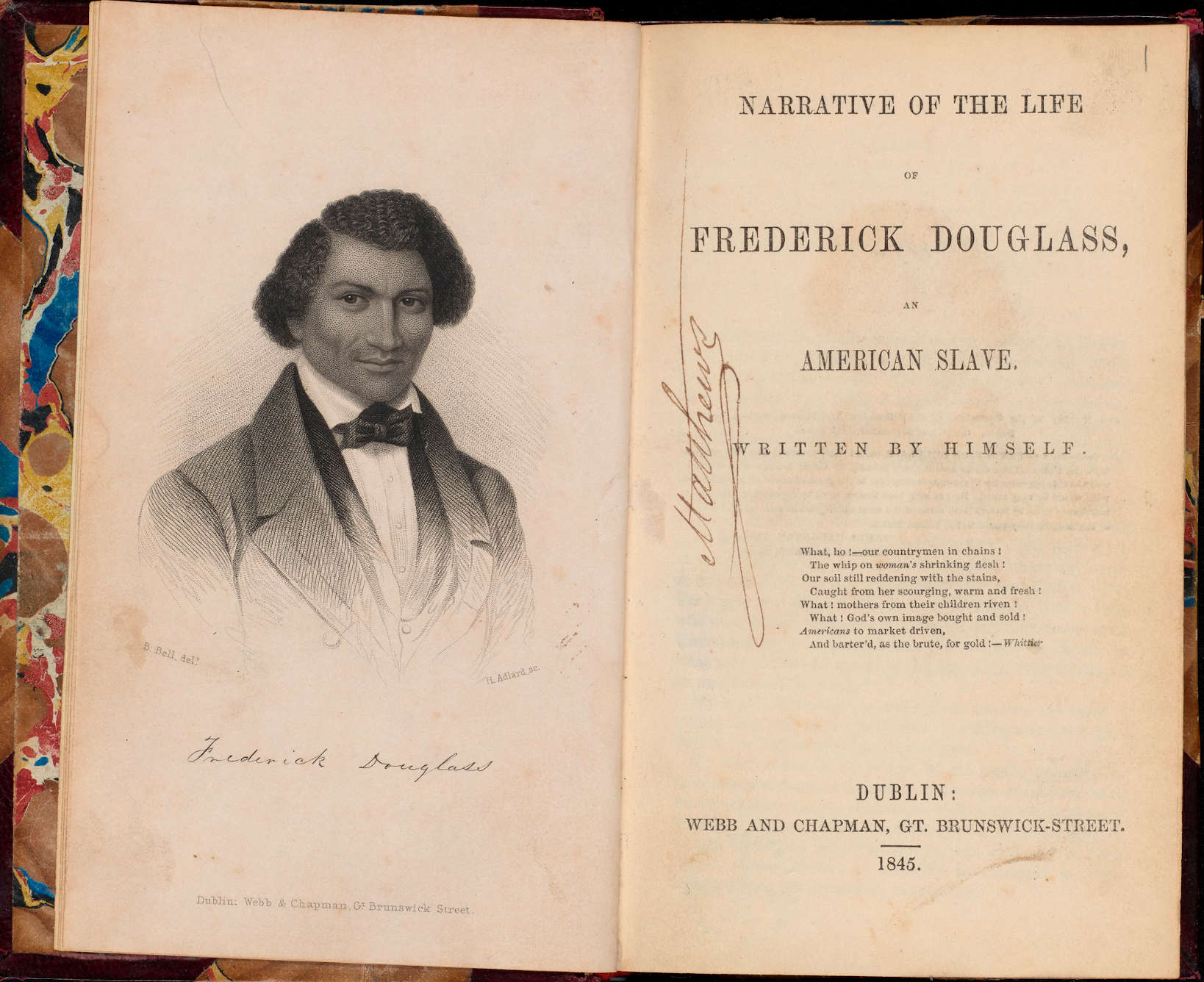

Frederick Douglass’s ‘Narrative’ includes an author portrait printed as the frontispiece opposite the title page.

Douglass despised the portrait included as a frontispiece to his 'Narrative' and executed by a white artist. He candidly admitted, ‘I don’t like it, and I have said without heat or thunder.’ He condemned this artistic reimagining of his face on the grounds that the white artist had made the decision to give it ‘a much more kindly and amiable expression, than is generally thought to characterize the face of the fugitive slave.’

Douglass despised the portrait included as a frontispiece to his 'Narrative' and executed by a white artist. He candidly admitted, ‘I don’t like it, and I have said without heat or thunder.’ He condemned this artistic reimagining of his face on the grounds that the white artist had made the decision to give it ‘a much more kindly and amiable expression, than is generally thought to characterize the face of the fugitive slave.’

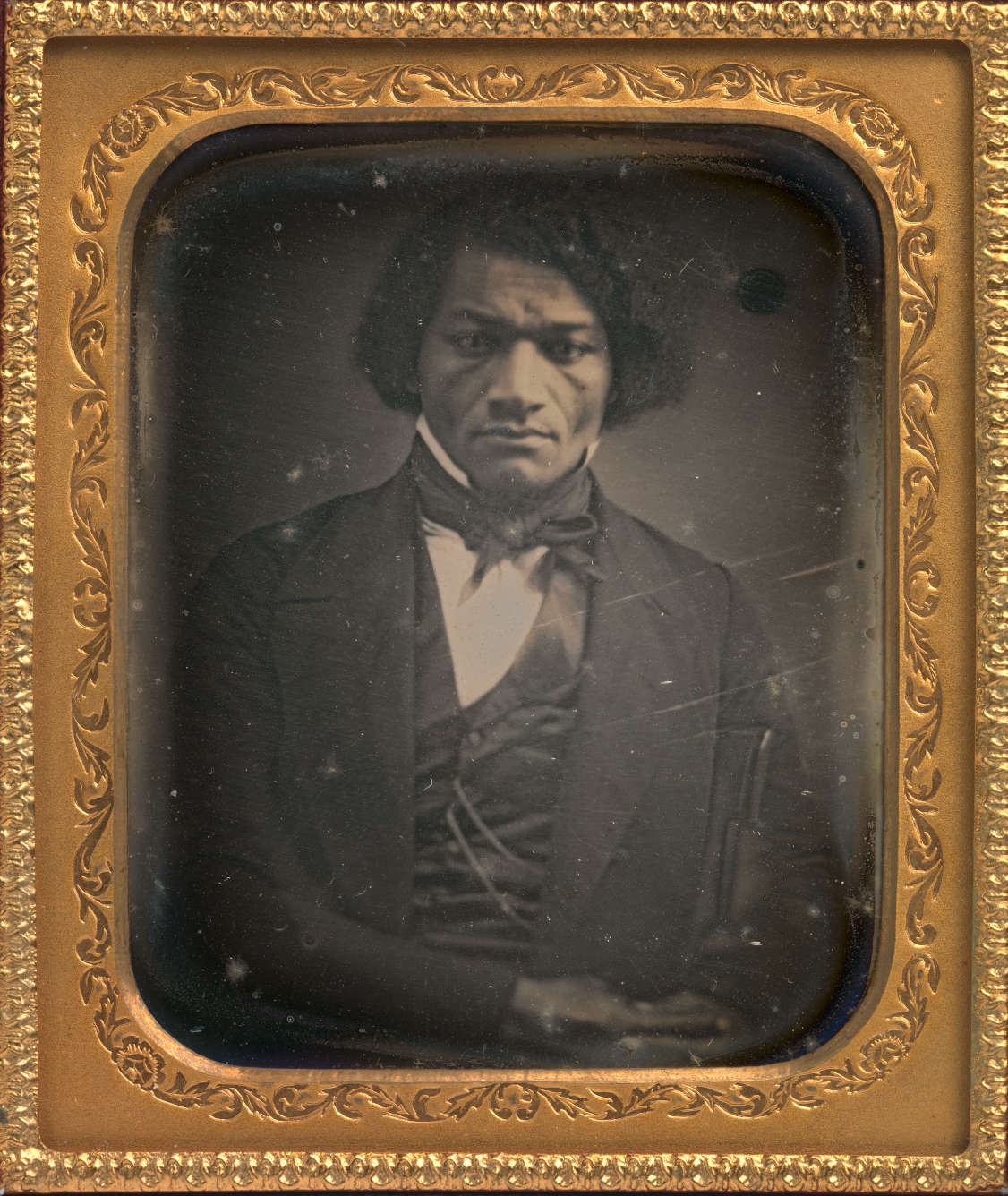

As a revolutionary means to annihilate any and all such white racist misrepresentations, Douglass believed in the power of photography. As the most photographed person in the United States in the 19th century, he endorsed the revolutionary power of the camera as the ideal mechanism by which to resist white racist caricatures of his face. As we see in the photograph of Douglass reproduced here, Douglass expressed the ‘face of the fugitive slave’: a face of sorrow, pain, suffering, and trauma. For Douglass, photography equipped African American women, children, and men with an antislavery weapon with which they were able to ‘see themselves’ as individual human subjects – and not as propertied objects – for the first time.

Extract from the ‘Narrative’:

‘...I never saw my mother, to know her as such, more than four or five times in my life; and each of these times was very short in duration, and at night. She was hired by a Mr. Stewart, who lived about twelve miles from my home. She made her journeys to see me in the night, travelling the whole distance on foot, after the performance of her day's work. She was a field hand, and a whipping is the penalty of not being in the field at sunrise, unless a slave has special permission from his or her master to the contrary - a permission which they seldom get, and one that gives to him that gives it the proud name of being a kind master. I do not recollect of ever seeing my mother by the light of day. She was with me in the night. She would lie down with me, and get me to sleep, but long before I waked she was gone. Very little communication ever took place between us. Death soon ended what little we could have while she lived, and with it her hardships and suffering. She died when I was about seven years old, on one of my master's farms, near Lee's Mill. I was not allowed to be present during her illness, at her death, or burial. She was gone long before I knew any thing about it. Never having enjoyed, to any considerable extent, her soothing presence, her tender and watchful care, I received the tidings of her death with much the same emotions I should have probably felt at the death of a stranger.

....

He was a cruel man, hardened by a long life of slaveholding. He would at times seem to take great pleasure in whipping a slave. I have often been awakened at the dawn of day by the most heart-rending shrieks of an own aunt of mine, whom he used to tie up to a joist, and whip upon her naked back till she was literally covered with blood. No words, no tears, no prayers, from his gory victim, seemed to move his iron heart from its bloody purpose. The louder she screamed, the harder he whipped; and where the blood ran fastest, there he whipped longest. He would whip her to make her scream, and whip her to make her hush; and not until overcome by fatigue, would he cease to swing the blood-clotted cowskin. I remember the first time I ever witnessed this horrible exhibition. I was quite a child, but I well remember it. I never shall forget it whilst I remember any thing. It was the first of a long series of such outrages, of which I was doomed to be a witness and a participant. It struck me with awful force. It was the blood-stained gate, the entrance to the hell of slavery, through which I was about to pass. It was a most terrible spectacle. I wish I could commit to paper the feelings with which I beheld it.’