‘You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man.’

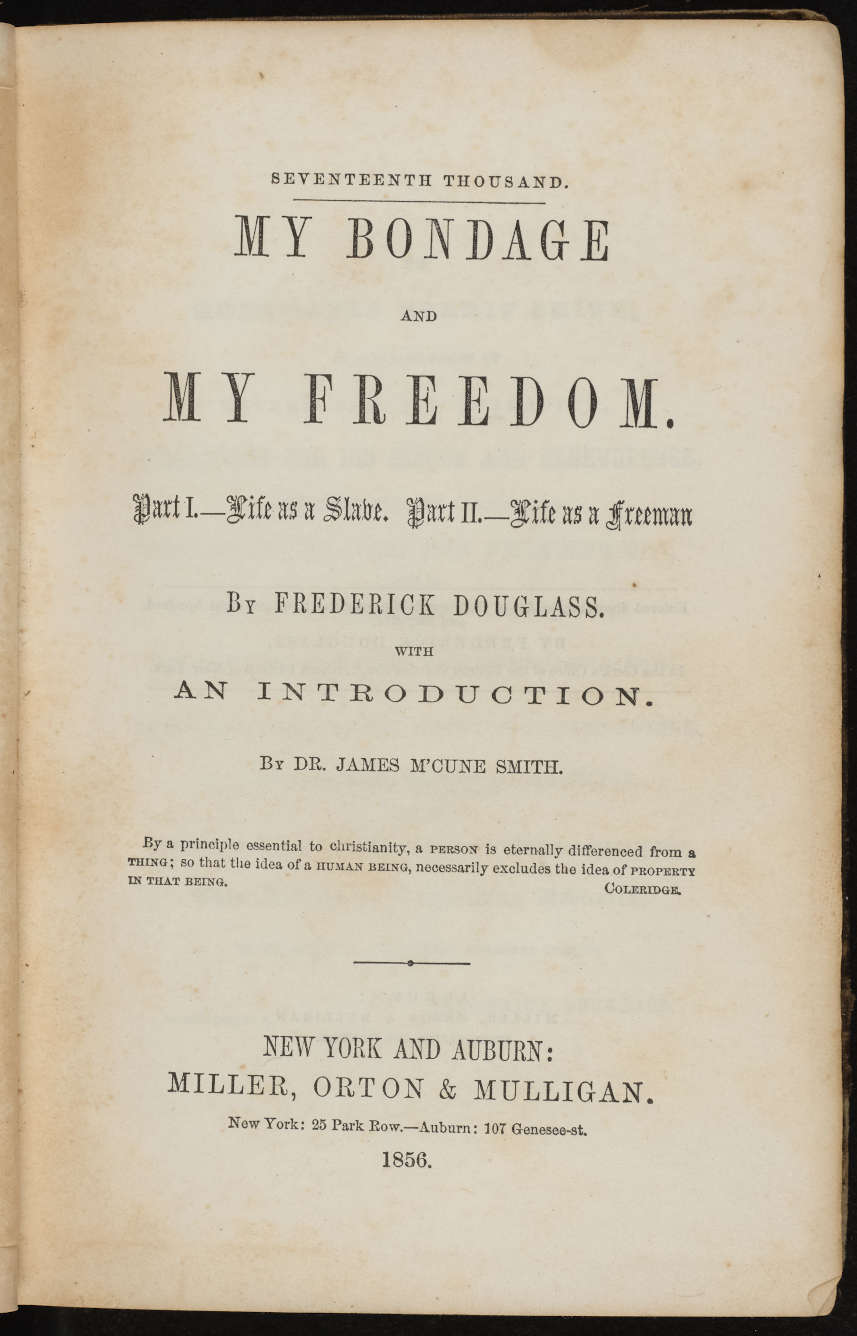

Frederick Douglass was inspired by one principle in writing his first autobiography, ‘Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave’ (1845): ‘to tell the story of the slave’ and protest against the ‘atrocious cruelty’ of white enslavers. Writing his second narrative in 1855, ‘My Bondage and My Freedom’, his determination was no longer simply ‘to tell the story of the slave’ but to critique, interrogate, philosophise, and denounce his ‘life as a slave’ and his ‘life as a freeman.’ He was under no illusion that the lived experiences of ‘bondage’ and freedom’ remained no absolute categories of existence. Rather, they were relative states of being and non-being for self-emancipated women and men fighting for survival in the United States.

Douglass warred against a ‘bondage’ that was not only the legal system of US chattel slavery but which encompassed all forms of white supremacist political, psychological and national persecution. He relied on ‘the ragged style of a slave’s pen’ in ‘My Bondage and My Freedom’ to celebrate the right of every Black woman, child and man to authorial, imaginative, philosophical and existential declarations of independence in the fight for equal rights and all freedoms.

Extract:

‘Much interest was awakened--large meetings assembled. Many came, no doubt, from curiosity to hear what a negro could say in his own cause. I was generally introduced as a "chattel"--a "thing"--a piece of southern "property"--the chairman assuring the audience that it could speak. Fugitive slaves, at that time, were not so plentiful as now; and as a fugitive slave lecturer, I had the advantage of being a "brand new fact"--the first one out. Up to that time, a colored man was deemed a fool who confessed himself a runaway slave, not only because of the danger to which he exposed himself of being retaken, but because it was a confession of a very low origin! Some of my colored friends in New Bedford thought very badly of my wisdom for thus exposing and degrading myself. The only precaution I took, at the beginning, to prevent Master Thomas from knowing where I was, and what I was about, was the withholding my former name, my master's name, and the name of the state and county from which I came. During the first three or four months, my speeches were almost exclusively made up of narrations of my own personal experience as a slave. "Let us have the facts," said the people. So also said Friend George Foster, who always wished to pin me down to my simple narrative. "Give us the facts," said Collins, "we will take care of the philosophy." Just here arose some embarrassment. It was impossible for me to repeat the same old story month after month, and to keep up my interest in it. It was new to the people, it is true, but it was an old story to me; and to go through with it night after night, was a task altogether too mechanical for my nature. "Tell your story, Frederick," would whisper my then revered friend, William Lloyd Garrison, as I stepped upon the platform. I could not always obey, for I was now reading and thinking. New views of the subject were presented to my mind. It did not entirely satisfy me to narrate wrongs; I felt like denouncing them. I could not always curb my moral indignation for the perpetrators of slaveholding villainy, long enough for a circumstantial statement of the facts which I felt almost everybody must know. Besides, I was growing, and needed room. "People won't believe you ever was a slave, Frederick, if you keep on this way," said Friend Foster. "Be yourself," said Collins, "and tell your story." It was said to me, "Better have a little of the plantation manner of speech than not; 'tis not best that you seem too learned." These excellent friends were actuated by the best of motives, and were not altogether wrong in their advice; and still I must speak just the word that seemed to me the word to be spoken by me.’