Armament > Conference for the control of the international trade in arms, munitions and implements of war

(106)

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

— 104

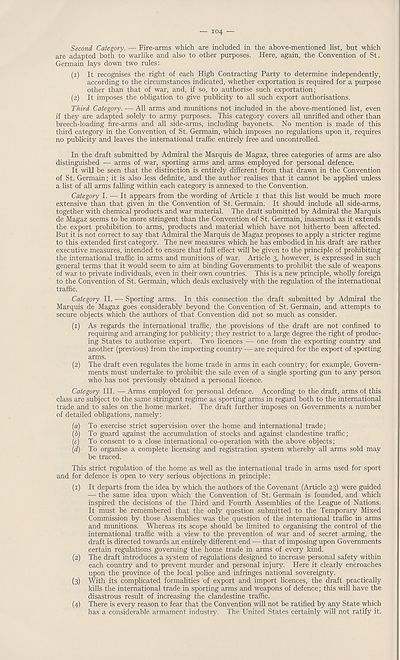

Second Category. — Fire-arms which are included in the above-mentioned list, but which

are adapted both to warlike and also to other purposes. Here, again, the Convention of St.

Germain lays down two rules:

(1) It recognises the right of each High Contracting Party to determine independently,

according to the circumstances indicated, whether exportation is required for a purpose

other than that of war, and, if so, to authorise such exportation;

(2) It imposes the obligation to give publicity to all such export authorisations.

Third Category. •— All arms and munitions not included in the above-mentioned list, even

if they are adapted solely to army purposes. This category covers all unrifled and other than

breech-loading fire-arms and all side-arms, including bayonets. No mention is made of this

third category in the Convention of St. Germain, which imposes no regulations upon it, requires

no publicity and leaves the international traffic entirely free and uncontrolled.

In the draft submitted by Admiral the Marquis de Magaz, three categories of arms are also

distinguished — arms of war, sporting arms and arms employed for personal defence.

It will be seen that the distinction is entirely different from that drawn in the Convention

of St. Germain; it is also less definite, and the author realises that it cannot be applied unless

a list of all arms falling within each category is annexed to the Convention.

Category I. — It appears from the wording of Article 1 that this list would be much more

extensive than that given in the Convention of St. Germain. It should include all side-arms,

together with chemical products and war material. The draft submitted by Admiral the Marquis

de Magaz seems to be more stringent than the Convention of St. Germain, inasmuch as it extends

the export prohibition to arms, products and material which have not hitherto been affected.

But it is not correct to say that Admiral the Marquis de Magaz proposes to apply a stricter regime

to this extended first category. The new measures which he has embodied in his draft are rather

executive measures, intended to ensure that full effect will be given to the principle of prohibiting

the international traffic in arms and munitions of war. Article 3, however, is expressed in such

general terms that it would seem to aim at binding Governments to prohibit the sale of weapons

of war to private individuals, even in their own countries. This is a new principle, wholly foreign

to the Convention of St. Germain, which deals exclusively with the regulation of the international

traffic.

Category II. •— Sporting arms. In this connection the draft submitted by Admiral the

Marquis de Magaz goes considerably beyond the Convention of St. Germain, and attempts to

secure objects which the authors of that Convention did not so much as consider.

(1) As regards the international traffic, the provisions of the draft are not confined to

requiring and arranging for publicity; they restrict to a large degree the right of produc¬

ing States to authorise export. Two licences — one from the exporting country and

another (previous) from the importing country — are required for the export of sporting

arms.

(2) The draft even regulates the home trade in arms in each country; for example, Govern¬

ments must undertake to prohibit the sale even of a single sporting gun to any person

who has not previously obtained a personal licence.

Category III. ■— Arms employed for personal defence. According to the draft, arms of this

class are subject to the same stringent regime as sporting arms in regard both to the international

trade and to sales on the home market. The draft further imposes on Governments a number

of detailed obligations, namely:

(a) To exercise strict supervision over the home and international trade;

(b) To guard against the accumulation of stocks and against clandestine traffic;

(c) To consent to a close international co-operation with the above objects;

{d) To organise a complete licensing and registration system whereby all arms sold may

be traced.

This strict regulation of the home as well as the international trade in arms used for sport

and for defence is open to very serious objections in principle:

(1) It departs from the idea by which the authors of the Covenant (Article 23) were guided

— the same idea upon which the Convention of St. Germain is founded, and which

inspired the decisions of the Third and Fourth Assemblies of the League of Nations.

It must be remembered that the only question submitted to the Temporary Mixed

Commission by those Assemblies was the question of the international traffic in arms

and munitions. Whereas its scope should be limited to organising the control of the

international traffic with a view to the prevention of war and of secret arming, the

draft is directed towards an entirely different end •— that of imposing upon Governments

certain regulations governing the home trade in arms of every kind.

(2) The draft introduces a system of regulations designed to increase personal safety within

each country and to prevent murder and personal injury. Here it clearly encroaches

upon the province of the local police and infringes national sovereignty.

(3) With its complicated formalities of export and import licences, the draft practically

kills the international trade in sporting arms and weapons of defence; this will have the

disastrous result of increasing the clandestine traffic.

(4) There is every reason to fear that the Convention will not be ratified by any State which

has a considerable armament industiy. The United States certainly will not ratify it.

Second Category. — Fire-arms which are included in the above-mentioned list, but which

are adapted both to warlike and also to other purposes. Here, again, the Convention of St.

Germain lays down two rules:

(1) It recognises the right of each High Contracting Party to determine independently,

according to the circumstances indicated, whether exportation is required for a purpose

other than that of war, and, if so, to authorise such exportation;

(2) It imposes the obligation to give publicity to all such export authorisations.

Third Category. •— All arms and munitions not included in the above-mentioned list, even

if they are adapted solely to army purposes. This category covers all unrifled and other than

breech-loading fire-arms and all side-arms, including bayonets. No mention is made of this

third category in the Convention of St. Germain, which imposes no regulations upon it, requires

no publicity and leaves the international traffic entirely free and uncontrolled.

In the draft submitted by Admiral the Marquis de Magaz, three categories of arms are also

distinguished — arms of war, sporting arms and arms employed for personal defence.

It will be seen that the distinction is entirely different from that drawn in the Convention

of St. Germain; it is also less definite, and the author realises that it cannot be applied unless

a list of all arms falling within each category is annexed to the Convention.

Category I. — It appears from the wording of Article 1 that this list would be much more

extensive than that given in the Convention of St. Germain. It should include all side-arms,

together with chemical products and war material. The draft submitted by Admiral the Marquis

de Magaz seems to be more stringent than the Convention of St. Germain, inasmuch as it extends

the export prohibition to arms, products and material which have not hitherto been affected.

But it is not correct to say that Admiral the Marquis de Magaz proposes to apply a stricter regime

to this extended first category. The new measures which he has embodied in his draft are rather

executive measures, intended to ensure that full effect will be given to the principle of prohibiting

the international traffic in arms and munitions of war. Article 3, however, is expressed in such

general terms that it would seem to aim at binding Governments to prohibit the sale of weapons

of war to private individuals, even in their own countries. This is a new principle, wholly foreign

to the Convention of St. Germain, which deals exclusively with the regulation of the international

traffic.

Category II. •— Sporting arms. In this connection the draft submitted by Admiral the

Marquis de Magaz goes considerably beyond the Convention of St. Germain, and attempts to

secure objects which the authors of that Convention did not so much as consider.

(1) As regards the international traffic, the provisions of the draft are not confined to

requiring and arranging for publicity; they restrict to a large degree the right of produc¬

ing States to authorise export. Two licences — one from the exporting country and

another (previous) from the importing country — are required for the export of sporting

arms.

(2) The draft even regulates the home trade in arms in each country; for example, Govern¬

ments must undertake to prohibit the sale even of a single sporting gun to any person

who has not previously obtained a personal licence.

Category III. ■— Arms employed for personal defence. According to the draft, arms of this

class are subject to the same stringent regime as sporting arms in regard both to the international

trade and to sales on the home market. The draft further imposes on Governments a number

of detailed obligations, namely:

(a) To exercise strict supervision over the home and international trade;

(b) To guard against the accumulation of stocks and against clandestine traffic;

(c) To consent to a close international co-operation with the above objects;

{d) To organise a complete licensing and registration system whereby all arms sold may

be traced.

This strict regulation of the home as well as the international trade in arms used for sport

and for defence is open to very serious objections in principle:

(1) It departs from the idea by which the authors of the Covenant (Article 23) were guided

— the same idea upon which the Convention of St. Germain is founded, and which

inspired the decisions of the Third and Fourth Assemblies of the League of Nations.

It must be remembered that the only question submitted to the Temporary Mixed

Commission by those Assemblies was the question of the international traffic in arms

and munitions. Whereas its scope should be limited to organising the control of the

international traffic with a view to the prevention of war and of secret arming, the

draft is directed towards an entirely different end •— that of imposing upon Governments

certain regulations governing the home trade in arms of every kind.

(2) The draft introduces a system of regulations designed to increase personal safety within

each country and to prevent murder and personal injury. Here it clearly encroaches

upon the province of the local police and infringes national sovereignty.

(3) With its complicated formalities of export and import licences, the draft practically

kills the international trade in sporting arms and weapons of defence; this will have the

disastrous result of increasing the clandestine traffic.

(4) There is every reason to fear that the Convention will not be ratified by any State which

has a considerable armament industiy. The United States certainly will not ratify it.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| League of Nations > Armament > Conference for the control of the international trade in arms, munitions and implements of war > (106) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/195383141 |

|---|

| Shelfmark | LN.IX |

|---|

| Description | Over 1,200 documents from the non-political organs of the League of Nations that dealt with health, disarmament, economic and financial matters for the duration of the League (1919-1945). Also online are statistical bulletins, essential facts, and an overview of the League by the first Secretary General, Sir Eric Drummond. These items are part of the Official Publications collection at the National Library of Scotland. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|