Legal > Conditions of voting requests for advisory opinions from the Permanent Court of International Justice

(11)

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

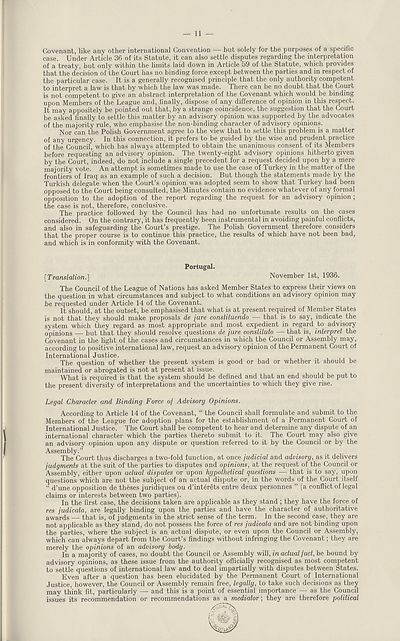

— 11 —

Covenant, like any other international Convention — but solely for the purposes of a specific

case. Under Article 36 of its Statute, it can also settle disputes regarding the interpretation

of a treaty, but only within the limits laid down in Article 59 of the Statute, which provides

that the decision of the Court has no binding force except between the parties and in respect of

the particular case. It is a generally recognised principle that the only authority competent

to interpret a law is that by which the law was made. There can be no doubt that the Court

is not competent to give an abstract interpretation of the Covenant which would be binding

upon Members of the League and, finally, dispose of any difference of opinion in this respect.

It may appositely be pointed out that, by a strange coincidence, the suggestion that the Court

be asked finally to settle this matter by an advisory opinion was supported by the advocates

of the majority rule, who emphasise the non-binding character of advisory opinions.

Nor can the Polish Government agree to the view that to settle this problem is a matter

of any urgency. In this connection, it prefers to be guided by the wise and prudent practice

of the Council, which has always attempted to obtain the unanimous consent of its Members

before requesting an advisory opinion. The twenty-eight advisory opinions hitherto given

by the Court, indeed, do not include a single precedent for a request decided upon by a mere

majority vote. An attempt is sometimes made to use the case of Turkey in the matter of the

frontiers of Iraq as an example of such a decision. But though the statements made by the

Turkish delegate when the Court’s opinion was adopted seem to show that Turkey had been

opposed to the Court being consulted, the Minutes contain no evidence whatever of any formal

opposition to the adoption of the report regarding the request for an advisory opinion ;

the case is not, therefore, conclusive.

The practice followed by the Council has had no unfortunate results on the cases

considered. On the contrary, it has frequently been instrumental in avoiding painful conflicts,

and also in safeguarding the Court’s prestige. The Polish Government therefore considers

that the proper course is to continue this practice, the results of which have not been bad,

and which is in conformity with the Covenant.

Portugal.

[Translation.] November 1st, 1936.

The Council of the League of Nations has asked Member States to express their views on

the question in what circumstances and subject to what conditions an advisory opinion may

be requested under Article 14 of the Covenant.

It should, at the outset, be emphasised that what is at present required of Member States

is not that they should make proposals de jure constituendo — that is to say, indicate the

system which they regard as most appropriate and most expedient in regard to advisory

opinions — but that they should resolve questions de jure conslitulo — that is, interpret the

Covenant in the light of the cases and circumstances in which the Council or Assembly may,

according to positive international law, request an advisory opinion of the Permanent Court of

International Justice.

The question of whether the present system is good or bad or whether it should be

maintained or abrogated is not at present at issue.

What is required is that the system should be defined and that an end should be put to

the present diversity of interpretations and the uncertainties to which they give rise.

Legal Character and Binding Force of Advisory Opinions.

According to Article 14 of the Covenant, “ the Council shall formulate and submit to the

Members of the League for adoption plans for the establishment of a Permanent Court of

International Justice. The Court shall be competent to hear and determine any dispute of an

international character which the parties thereto submit to it. The Court may also give

an advisory opinion upon any dispute or question referred to it by the Council or by the

Assembly.”

The Court thus discharges a two-fold function, at once judicial and advisory, as it delivers

judgments at the suit of the parties to disputes and opinions, at the request of the Council or

Assembly, either upon actual disputes or upon hypothetical questions — that is to say, upon

questions which are not the subject of an actual dispute or, in the words of the Court itself

“ d’une opposition de theses juridiques ou d’interets entre deux personnes ” (a conflict of legal

claims or interests between two parties).

In the first case, the decisions taken are applicable as they stand ; they have the force of

res judicata, are legally binding upon the parties and have the character of authoritative

awards — that is, of judgments in the strict sense of the term. In the second case, they are

not applicable as they stand, do not possess the force of res judicata and are not binding upon

the parties, where the subject is an actual dispute, or even upon the Council or Assembly,

which can always depart from the Court’s findings without infringing the Covenant; they are

merely the opinions of an advisory body.

In a majority of cases, no doubt the Council or Assembly will, in actual fact, be bound by

advisory opinions, as these issue from the authority officially recognised as most competent

to settle questions of international law and to deal impartially with disputes between States.

Even after a question has been elucidated by the Permanent Court of International

Justice, however, the Council or Assembly remain free, legally, to take such decisions as they

may think fit, particularly — and this is a point of essential importance — as the Council

issues its recommendation or recommendations as a mediator; they are therefore political

Covenant, like any other international Convention — but solely for the purposes of a specific

case. Under Article 36 of its Statute, it can also settle disputes regarding the interpretation

of a treaty, but only within the limits laid down in Article 59 of the Statute, which provides

that the decision of the Court has no binding force except between the parties and in respect of

the particular case. It is a generally recognised principle that the only authority competent

to interpret a law is that by which the law was made. There can be no doubt that the Court

is not competent to give an abstract interpretation of the Covenant which would be binding

upon Members of the League and, finally, dispose of any difference of opinion in this respect.

It may appositely be pointed out that, by a strange coincidence, the suggestion that the Court

be asked finally to settle this matter by an advisory opinion was supported by the advocates

of the majority rule, who emphasise the non-binding character of advisory opinions.

Nor can the Polish Government agree to the view that to settle this problem is a matter

of any urgency. In this connection, it prefers to be guided by the wise and prudent practice

of the Council, which has always attempted to obtain the unanimous consent of its Members

before requesting an advisory opinion. The twenty-eight advisory opinions hitherto given

by the Court, indeed, do not include a single precedent for a request decided upon by a mere

majority vote. An attempt is sometimes made to use the case of Turkey in the matter of the

frontiers of Iraq as an example of such a decision. But though the statements made by the

Turkish delegate when the Court’s opinion was adopted seem to show that Turkey had been

opposed to the Court being consulted, the Minutes contain no evidence whatever of any formal

opposition to the adoption of the report regarding the request for an advisory opinion ;

the case is not, therefore, conclusive.

The practice followed by the Council has had no unfortunate results on the cases

considered. On the contrary, it has frequently been instrumental in avoiding painful conflicts,

and also in safeguarding the Court’s prestige. The Polish Government therefore considers

that the proper course is to continue this practice, the results of which have not been bad,

and which is in conformity with the Covenant.

Portugal.

[Translation.] November 1st, 1936.

The Council of the League of Nations has asked Member States to express their views on

the question in what circumstances and subject to what conditions an advisory opinion may

be requested under Article 14 of the Covenant.

It should, at the outset, be emphasised that what is at present required of Member States

is not that they should make proposals de jure constituendo — that is to say, indicate the

system which they regard as most appropriate and most expedient in regard to advisory

opinions — but that they should resolve questions de jure conslitulo — that is, interpret the

Covenant in the light of the cases and circumstances in which the Council or Assembly may,

according to positive international law, request an advisory opinion of the Permanent Court of

International Justice.

The question of whether the present system is good or bad or whether it should be

maintained or abrogated is not at present at issue.

What is required is that the system should be defined and that an end should be put to

the present diversity of interpretations and the uncertainties to which they give rise.

Legal Character and Binding Force of Advisory Opinions.

According to Article 14 of the Covenant, “ the Council shall formulate and submit to the

Members of the League for adoption plans for the establishment of a Permanent Court of

International Justice. The Court shall be competent to hear and determine any dispute of an

international character which the parties thereto submit to it. The Court may also give

an advisory opinion upon any dispute or question referred to it by the Council or by the

Assembly.”

The Court thus discharges a two-fold function, at once judicial and advisory, as it delivers

judgments at the suit of the parties to disputes and opinions, at the request of the Council or

Assembly, either upon actual disputes or upon hypothetical questions — that is to say, upon

questions which are not the subject of an actual dispute or, in the words of the Court itself

“ d’une opposition de theses juridiques ou d’interets entre deux personnes ” (a conflict of legal

claims or interests between two parties).

In the first case, the decisions taken are applicable as they stand ; they have the force of

res judicata, are legally binding upon the parties and have the character of authoritative

awards — that is, of judgments in the strict sense of the term. In the second case, they are

not applicable as they stand, do not possess the force of res judicata and are not binding upon

the parties, where the subject is an actual dispute, or even upon the Council or Assembly,

which can always depart from the Court’s findings without infringing the Covenant; they are

merely the opinions of an advisory body.

In a majority of cases, no doubt the Council or Assembly will, in actual fact, be bound by

advisory opinions, as these issue from the authority officially recognised as most competent

to settle questions of international law and to deal impartially with disputes between States.

Even after a question has been elucidated by the Permanent Court of International

Justice, however, the Council or Assembly remain free, legally, to take such decisions as they

may think fit, particularly — and this is a point of essential importance — as the Council

issues its recommendation or recommendations as a mediator; they are therefore political

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| League of Nations > Legal > Conditions of voting requests for advisory opinions from the Permanent Court of International Justice > (11) |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/191518055 |

|---|

| Shelfmark | LN.V |

|---|

| Description | Over 1,200 documents from the non-political organs of the League of Nations that dealt with health, disarmament, economic and financial matters for the duration of the League (1919-1945). Also online are statistical bulletins, essential facts, and an overview of the League by the first Secretary General, Sir Eric Drummond. These items are part of the Official Publications collection at the National Library of Scotland. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|