About the collection

About the collection

Veterinary medicine

The Medical History of British India veterinary collection reveals how British veterinarians used new research to expand their empire and aid the indigenous. It demonstrates how colonial veterinary policies were shaped by military, financial, political and scientific factors.

Veterinary diseases

Animals as military transport

Before the First World War, animals provided the sole source of motive power for armies, carrying men, weapons, troops and supplies. veterinary medicine was as much a technology of power as human medicine, improving military efficiency, facilitating imperial expansion and guaranteeing British hegemony.

The Medical History of British India veterinary diseases reports include military reports on trypanosomiasis or 'surra' (meaning 'gone rotten'), a chronic blood disorder primarily affecting horses, camels and elephants. Army Veterinary Department (AVD) reports include historical accounts and personal testimonies of officers which reveal the effects of surra on military operations.

As veterinary medicine facilitated imperial expansion, imperialism benefited veterinarians by providing new diseases to explore. AVD reports portray how the work of veterinarians contributed to scientific debates on the role of microorganisms in disease transmission after Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch introduced the germ theory of disease in the 1860s.

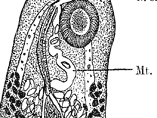

Bacteriological investigations into surra

Welsh bacteriologist Griffith Evans conducted experiments which demonstrated that a 'trypanosome' (a uni-cellular micro-organism) was responsible for the spread of surra. It was previously believed that the trypanosome was a symptom rather than the cause of the disease, which they attributed to purely chemical factors.

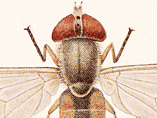

Reports by the Imperial Bacteriologist show how Evans' work was developed. Hypothesis that flies were the vector of the disease was substantiated for the first time in 1909. Reports of the government camel specialist show the practical significance of this discovery, for example by enabling authorities to compile lists of surra-zones which commandants of camel corps could avoid.

Addressing and assessing rinderpest

While much of the veterinary disease material relates to surra, a disease which mostly threatened the military, Dr Charles Palmer's report on rinderpest focuses on the civil, agricultural sphere.

Rinderpest, or cattle plague, is a virulent and contagious viral disease which was responsible for more bovine deaths than any other disease in India. The report offers a valuable insight into how veterinarians, doctors and European livestock owners imagined the disease and how it spread.

It can be used to examine why rinderpest was marked as a problem and placed on the political agenda in the 1860s when the disease had been endemic in India for centuries.

Veterinary colleges and laboratories

The purpose of British veterinary colleges in India

The British veterinary colleges established in India in the late 19th century produced veterinary assistants for both the military and the Civil Veterinary Departments, although some historians argue that it was the military which benefited the most.

The veterinary colleges formed part of a wider, ideologically motivated attempt to replace Hindu veterinary science ('mrgayurveda') with western veterinary science. Undermining indigenous science allowed Indians to be portrayed as children, in terms of scientific achievements, which helped to justify British paternalistic, authoritarian rule.

As the number of British vets in India was small, Indian veterinary assistants were crucial to attempts to diffuse western veterinary knowledge to the Indian population.

The Medical History of British India Veterinary colleges material relates to the Bombay veterinary college and includes statements of rules and regulations, examinations, admission criteria, and disciplinary procedures.

Aspects of student life indicate how not only the education but the social lives of veterinary students were regulated. Extra-curricular sports and exercise programmes were mandatory, designed to promote manliness and foster practical animal handling skills.

The limitations of attempts to shape Indian veterinary practitioners are also expressed, particularly after graduation when subordinates were poorly supervised and often reverted to traditional Indian veterinary practices.

Indian veterinarians

Details of the career trajectories of graduates are included in the Bombay veterinary colleges reports, which provide an indication of the limited demand for western veterinary medicine in India. Few graduates went into private practice. Most went into civil or military government service, suggesting that practitioners of western veterinary medicine were reliant on government subsidies to make a living.

The racial and caste backgrounds of students provide an insight into the order of colonial labour and how notions of race impacted upon educational strategies.

Particularly striking is the preference shown for high-caste candidates, despite the belief that lower-caste recruits from rural areas had more practical experience handling animals.

The Imperial Bacteriological Laboratory

The Imperial Bacteriological Laboratory (IBL) was established in Poona in 1891 and initially focused on surra. The digitised reports cover 1895-1933.

In 1895 it was relocated to Muktesar in the Kumaon hills where the cooler climate facilitated research into rinderpest – a disease of greater relevance to Indian cattle owners. The laboratory exists today as the Indian Veterinary Research Institute.

The Medical History of British India Veterinary laboratory reports cover research work into surra and rinderpest between 1895 and 1933 as well as the routine production of immune sera and inoculations.

Some historians argue that colonial science was primarily concerned with the solution of practical problems and that original research suffered as a result. The Imperial bacteriologist did complain on occasion that the IBL had become a mere 'production line' for sera.

The nature and transmission of knowledge

However, laboratory reports illustrate how even routine work led to original research, such as the investigations into anaphylaxis which was intended to make serum production more efficient.

The Annual Report of the Imperial Bacteriologist demonstrates the influence of scientists not only at the forefront of research but from other colonial contexts, such as Robert Koch's visit to India described in the 1897-1898 report.

This demonstrates the complex flow of scientific knowledge between colonial scientists and that scientific thought did not simply flow from European 'metropole' to colonial 'periphery'.

The Civil Veterinary Departments

Motives for establishment of Civil Veterinary Departments

The first British veterinarians to arrive in India were military officers, and for most of the 19th century their work was restricted to caring for military transport animals.

In 1892 a Civil Veterinary Department (CVD) was established to control disease and improve breeding of civil stock. The decision partly reflected the belief that veterinary medicine could alleviate social problems such as famine while providing an indication of colonial 'benevolence'.

The CVD reports cover 1892-1951 and show veterinary medicine exploiting imperial resources more efficiently. However, pragmatic concerns over military cost and efficiency partly influenced the establishment of a civil department. The CVD provided a reserve of veterinarians in India in case of war, and continued to breed horses for cavalry regiments until 1904.

Evidence is provided by the CVD reports of the extent to which rhetoric about using veterinary medicine to increase revenue and solve social problems were translated into practice.

Comparisons between Indian provinces

An India-wide overview of disease mortality, expenditure on veterinary objectives, numbers of dispensary patients, inoculations, castrations and breeding operations is provided by Central CVD reports.

Provincial CVD reports supply a detailed regional perspective, revealing the diversity of disease incidence and the varied nature of disease measures implemented. The Madras CVD was the only department to make inoculation against rinderpest compulsory, and elsewhere education programmes rather than legislation were used to persuade livestock owners to inoculate.

The CVD reports reveal significant differences funding between provincial CVDs. In 1909 one quarter of all veterinary expenditure was allocated in the Punjab and by 1929 one third of all cases of animal illnesses in India were treated in this one province.

The effectiveness of veterinary intervention and its impact on local communities is explored in the CVD reports. Statistical appendices show that even the largest CVD reached only 15% of the total bovine population, and that fewer than 7% of cattle were inoculated in any given year. Consequently disease mortality statistics do not show significant reductions during the colonial period.

Efficacy of Civil Veterinary Department programmes

Cattle breeding programmes were also largely inconsequential and from 1912, when the CVD was placed under the agricultural department, veterinarians focused narrowly on controlling disease and injury, leaving the improvement of stock to agriculturalists. As late as the 1930s vets admitted that little had been done to improve stock or pasture grounds.

Why veterinary intervention was limited in scope and effectiveness is presented in the CVD reports. Veterinarians often attributed poor results of disease control measures to the alleged apathy and conservatism of Indian livestock owners. Although such self-serving notions are not compelling as explanations, the CVD reports show the extent to which the CVDs created and reflected British racial stereotypes.

Some historians suggest that British authorities exaggerated the impact of cultural objections to western medicine in order to justify inaction. Detailed financial records show the impact of financial stringency on veterinary intervention and the extent to which notions of cultural resistance to veterinary medicine were deployed strategically.

The CVD reports also contain the financial contributions of local authorities, which increasingly took charge of veterinary policy. These allow the role of Indian officials in shaping veterinary policy to be reconstructed and evaluated.

Key subjects:

- Disease »

- Institutions »

- Drugs »

- Veterinary medicine

- Mental health »

- Vaccination »