Medicine - Mental health > 1867-1924 - Annual report of the insane asylums in Bengal > Insane asylums in Bengal annual reports 1867-1875 > Annual report on the insane asylums in Bengal, for the year 1870

(329) Page 23

Download files

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

DULLUNDA ASYLUM. 23

food; but the men who do it are those whose voracity is but one of their many insane impulses,

—of the class whom no feeding can benefit, and of whom the death-list largely consists.

Those whose appearance would suggest that they are suffering from the rapacity of their

neighbours, are themselves the aggressors.

8. It may be asked if the main sources of mortality be outside the asylum, why such

pressing demands have been made on the Government for additional buildings. What can

accommodation in the asylum do to prevent illness in the town. The answer is easy. I do

not calculate on any marked effect of more room on the mortality ? It would have been no

less my duty to put forward the crowded state of the place for amendment if the death-rate

had been exceptionally low instead of high. That the breathing space available is far below

that which the most tolerant sanitary rules will sanction, and that a cachectic condition occurs

here as in other populous institutions, are reasons sufficient for the extension.

9. The industrial system of the asylum has a relation to its sanitary state scarcely less

close than that of diet; and as it has now attained its full development, after a gradual

growth of ten years, it will be useful and interesting to summarize the facts which those years

have brought forth, to indicate the bearing of labour on mortality. The effect of work on

health has been most sedulously watched throughout. No consideration of profit has been

allowed to prevail over the great objects of its introduction—discipline and cure. In forming

an opinion on the burthen and suitability of the forms of industry in use, it must be observed

that the task imposed on laborers elsewhere by soorkee-making, oil-mill, &c., is here indefi-

nitely reduced by dividing the labour of one between several, by limiting the hours of work

and imposing no fixed daily outturn. I will now confine myself to tracing the relation

between work and death as it is recorded in the history of the past ten years.

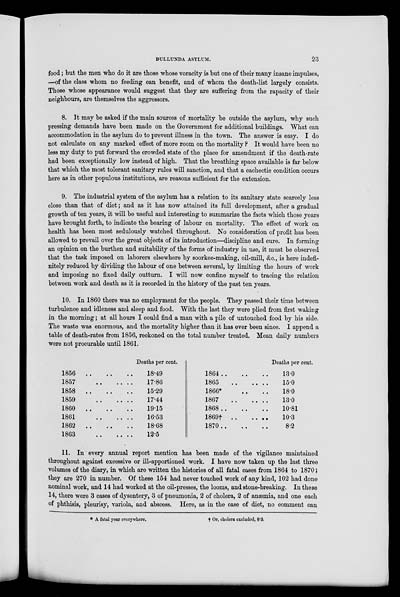

10. In 1860 there was no employment for the people. They passed their time between

turbulence and idleness and sleep and food. With the last they were plied from first waking

in the morning; at all hours I could find a man with a pile of untouched food by his side.

The waste was enormous, and the mortality higher than it has ever been since. I append a

table of death-rates from 1856, reckoned on the total number treated. Mean daily numbers

were not procurable until 1861.

|

Deaths per cent. |

|

|

1856 .. .. .. |

18.49 |

|

1857 .. .. .. |

17.86 |

|

1858 .. .. .. |

15.29 |

|

1859 .. .. .. |

17.44 |

|

1860 .. .. .. |

19.15 |

|

1861 .. .. .. |

16.53 |

|

1862 .. .. .. |

18.68 |

|

1863 .. .. .. |

12.5 |

|

Deaths per cent. |

|

|

1864 .. .. .. |

13.0 |

|

1865 .. .. .. |

15.0 |

|

1866* .. .. .. |

18.0 |

|

1867 .. .. .. |

13.0 |

|

1868 .. .. .. |

10.81 |

|

1869† .. .. .. |

10.3 |

|

1870 .. .. .. |

8.2 |

11. In every annual report mention has been made of the vigilance maintained

throughout against excessive or ill-apportioned work. I have now taken up the last three

volumes of the diary, in which are written the histories of all fatal cases from 1864 to 1870;

they are 270 in number. Of these 154 had never touched work of any kind, 102 had done

nominal work, and 14 had worked at the oil-presses, the looms, and stone-breaking. In these

14, there were 3 cases of dysentery, 3 of pneumonia, 2 of cholera, 2 of anæmia, and one each

of phthisis, pleurisy, variola, and abscess. Here, as in the case of diet, no comment can

* A fatal year everywhere. † Or, cholera excluded, 8.3.

Set display mode to: Large image | Zoom image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/83378993 |

|---|