Memorial as to the Ruthven peerage

(25) Page 21

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

21

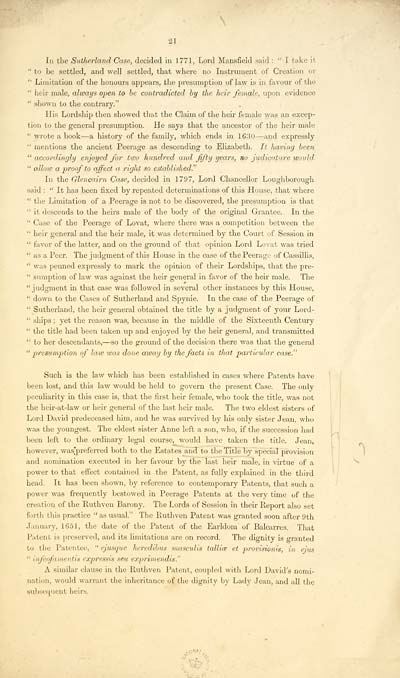

In the Sutherland Case, decided in 1771, Lord Mansfield said : " I take it

" to be settled, and well settled, that where no Instrument of Creation or

" Limitation of the honours appears, the presumption of law is in favour of the

" heir male, aliuays open to he contradicted by the heir female, upon evidence

" shown to the contrary."

His Lordship then showed that the Claim of the heir female was an excep-

tion to the general presumption. He says that the ancestor of the heir male

" wrote a book — a history of the family, which ends in 1630 — and expressly

" mentions the ancient Peerage as descending to Elizabeth. It having been

"accordingly enjoyed for two hundred and fifty years, no judicature would

" allow a proof to affect a right so established."

In the Glencairn Case, decided in 1797, Lord Chancellor Loughborough

said : " It has been fixed by repeated determinations of this House, that where

" the Limitation of a Peerage is not to be discovered, the presumption is that

" it descends to the heirs male of the body of the original Grantee. In the

" Case of the Peerage of Lovat, where there was a competition between the

" heir general and the heir male, it was determined by the Court of Session in

" favor of the latter, and on the ground of that opinion Lord Lovat was tried

" as a Peer. The judgment of this House in the case of the Peerage of Cassillis,

" was penned expressly to mark the opinion of their Lordships, that the pre-

" sumption of law was against the heir general in favor of the heir male. The

"judgment in that case was followed in several other instances by this House,

" down to the Cases of Sutherland and Spynie. In the case of the Peerage of

" Sutherland, the heir general obtained the title by a judgment of your Lord-

" ships ; yet the reason was, because in the middle of the Sixteenth Century

" the title had been taken up and enjoyed by the heir general, and transmitted

" to her descendants, — so the ground of the decision there was that the general

"presumption of law was done away by the facts in that particular case."

Such is the law which has been established in cases where Patents have

been lost, and this law would be held to govern the present Case. The only

peculiarity in this case is, that the first heir female, who took the title, was not

the heir-at-law or heir general of the last heir male. The two eldest sisters of

Lord David predeceased him, and he was survived by his only sister Jean, who

was the youngest. The eldest sister Anne left a son, who, if the succession had

been left to the ordinary legal course, would have taken the title. Jean,

however, was'preferred both to the Estates and to the Title by special provision

and nomination executed in her favour by the last heir male, in virtue of a

power to that effect contained in the Patent, as fully explained in the third

head. It has been shown, by reference to contemporary Patents, that such a

power was frequently bestowed in Peerage Patents at the very time of the

creation of the Ruthven Barony. The Lords of Session in their Report also set

forth this practice "as usual." The Ruthven Patent was granted soon after 9th

January, 1651, the date of the Patent of the Earldom of Balcarres. That

Patent is preserved, and its limitations are on record. The dignity is granted

to the Patentee, " ejusque heredibus masculis tallice et provisionis, in ejus

" infeofamentis expressis seu exprimendis."

A similar clause in the Ruthven Patent, coupled with Lord David's nomi-

nation, would warrant the inheritance of the dignity by Lady Jean, and all the

subsequent heirs.

<v

In the Sutherland Case, decided in 1771, Lord Mansfield said : " I take it

" to be settled, and well settled, that where no Instrument of Creation or

" Limitation of the honours appears, the presumption of law is in favour of the

" heir male, aliuays open to he contradicted by the heir female, upon evidence

" shown to the contrary."

His Lordship then showed that the Claim of the heir female was an excep-

tion to the general presumption. He says that the ancestor of the heir male

" wrote a book — a history of the family, which ends in 1630 — and expressly

" mentions the ancient Peerage as descending to Elizabeth. It having been

"accordingly enjoyed for two hundred and fifty years, no judicature would

" allow a proof to affect a right so established."

In the Glencairn Case, decided in 1797, Lord Chancellor Loughborough

said : " It has been fixed by repeated determinations of this House, that where

" the Limitation of a Peerage is not to be discovered, the presumption is that

" it descends to the heirs male of the body of the original Grantee. In the

" Case of the Peerage of Lovat, where there was a competition between the

" heir general and the heir male, it was determined by the Court of Session in

" favor of the latter, and on the ground of that opinion Lord Lovat was tried

" as a Peer. The judgment of this House in the case of the Peerage of Cassillis,

" was penned expressly to mark the opinion of their Lordships, that the pre-

" sumption of law was against the heir general in favor of the heir male. The

"judgment in that case was followed in several other instances by this House,

" down to the Cases of Sutherland and Spynie. In the case of the Peerage of

" Sutherland, the heir general obtained the title by a judgment of your Lord-

" ships ; yet the reason was, because in the middle of the Sixteenth Century

" the title had been taken up and enjoyed by the heir general, and transmitted

" to her descendants, — so the ground of the decision there was that the general

"presumption of law was done away by the facts in that particular case."

Such is the law which has been established in cases where Patents have

been lost, and this law would be held to govern the present Case. The only

peculiarity in this case is, that the first heir female, who took the title, was not

the heir-at-law or heir general of the last heir male. The two eldest sisters of

Lord David predeceased him, and he was survived by his only sister Jean, who

was the youngest. The eldest sister Anne left a son, who, if the succession had

been left to the ordinary legal course, would have taken the title. Jean,

however, was'preferred both to the Estates and to the Title by special provision

and nomination executed in her favour by the last heir male, in virtue of a

power to that effect contained in the Patent, as fully explained in the third

head. It has been shown, by reference to contemporary Patents, that such a

power was frequently bestowed in Peerage Patents at the very time of the

creation of the Ruthven Barony. The Lords of Session in their Report also set

forth this practice "as usual." The Ruthven Patent was granted soon after 9th

January, 1651, the date of the Patent of the Earldom of Balcarres. That

Patent is preserved, and its limitations are on record. The dignity is granted

to the Patentee, " ejusque heredibus masculis tallice et provisionis, in ejus

" infeofamentis expressis seu exprimendis."

A similar clause in the Ruthven Patent, coupled with Lord David's nomi-

nation, would warrant the inheritance of the dignity by Lady Jean, and all the

subsequent heirs.

<v

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Histories of Scottish families > Memorial as to the Ruthven peerage > (25) Page 21 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/95642731 |

|---|

| Description | A selection of almost 400 printed items relating to the history of Scottish families, mostly dating from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Includes memoirs, genealogies and clan histories, with a few produced by emigrant families. The earliest family history goes back to AD 916. |

|---|