Montgomery manuscripts

(217) Page 203

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

The Montgomery Manuscripts.

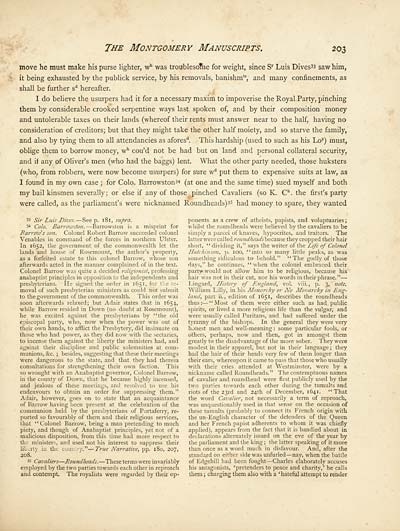

203

move he must make his purse lighter, w b was troublesome for weight, since S 1 ' Luis Divest saw him,

it being exhausted by the publick service, by his removals, banishm 18 , and many confinements, as

shall be further s d hereafter.

I do believe the usurpers had it for a necessary maxim to impoverise the Royal Party, pinching

them by considerable crooked serpentine ways last spoken of, and by their composition money

and untolerable taxes on their lands (whereof their rents must answer near to the half, having no

consideration of creditors; but that they might take the other half moiety, and so starve the family,

and also by tying them to all attendancies as afores d . This hardship (used to such as his Lo p ) must,

oblige them to borrow money, \v h cou'd not be had but on land and personal collateral security,

and if any of Oliver's men (who had the baggs) lent. What the other party needed, those huksters

(who, from robbers, were now become usurpers) for sure w d put them to expensive suits at law, as

I found in my own case ; for Colo. Barrowstons* (at one and the same time) sued myself and both

my bail kinsmen severally; or else if any of those pinched Cavaliers (so K. C h . the first's party

were called, as the parliament's were nicknamed Roundheads)3 s had money to spare, they wanted

33 Sir Luis Dives. — See p. 181, supra.

34 Colo. Barrowsttm. — Barrowston is a misprint for

Barrow's son. Colonel Robert Barrow succeeded colonel

Venables in command of the forces in northern Ulster.

In 1652, the government of the commonwealth let the

lands and house of Rosemount, the author's properly,

as a forfeited estate to this colonel Barrow, whose son

afterwards acted in the manner complained of in the text.

Colonel Barrow was quite a decided religionist, professing

anabaptist principles in opposition to the independents and

presbyterians. He signed the order in 1 651, for the re-

moval of such presbyterian ministers as could not submit

to the government of the commonwealth. This order was

soon afterwards relaxed; but Adair states that in 1654.,

while Barrow resided in Down (no doubt at Rosemount),

he was excited against the presbyterians by "the old

episcopal party, who, now when the power was out of

their own hands, to afflict the Presbytery, did insinuate on

those who had power, as they did now with the sectaries,

to incense them against the liberty the ministers had, and

against their discipline and public solemnities at com-

munions, &c. ; besides, suggesting that these their meetings

were dangerous to the state, and that they had therein

consultations for strengthening their own faction. This

so wrought with an Anabaptist governor, Colonel Barrow,

in the county of Down, that he became highly incensed,

and jealous of these meetings, and resolved to use his

endeavours to obtain an order for suppressing them."

Adair, however, goes on to state that an acquaintance

of Barrow having been present at the celebration of the

communion held by the presbyterians of Portaferry, re-

ported so favourably of them and their religious services,

that "Colonel Barrow, being a man pretending to much

piety, and though of Anabaptist principles, yet not of a

malicious disposition, from this time had more respect to

the ministers, and used not his interest to suppress their

liberty in the country." — True Narrative, pp. 180, 207,

208.

35 Cavaliers — Roundheads. — These terms were invariably

employed by the two parties towards each other in reproach

and contempt The royalists were regarded by their op-

ponents as a crew of atheists, papists, and voluptuaries ;

whilst the roundheads were believed by the cavaliers to be

simply a parcel of knaves, hypocrites, and traitors. The

latter were called roundheads because they cropped their hair

short, " dividing it," says the writer of the Life of Colonel

Hutchinson, p. ioo, "into so many little peaks, as was

something ridiculous to- behold." "The godly of those

days," he continues, "when the colonel embraced their

party would not allow him to be religious, because his

hair was not in their cut, nor his words in their phrase." —

Lingard, History of England, vol. viii. , p. 3, note.

William Lilly, in his Monarchy or No Monarchy in Eng-

land, part ii. , edition of 165 1, describes the roundheads

thus: — "Most of them were either such as had public

spirits, or lived a more religious life than the vulgar, and

were usually called Puritans, and had suffered under the

tyranny of the bishops. In the general they were very

honest men and well-meaning : some particular fools, or

others, perhaps, now and then, got in amongst them

greatly to the disadvantage of the more sober. They were

modest in their apparel, but not in their language ; they

had the hair of their heads very few of them longer than

their ears, whereupon it came to pass that those who usually

with their cries attended at Westminster, were by a

nickname called Roundheads." The contemptuous names

of cavalier and roundhead were first publicly used by the

two parties towards each other during the tumults and

riots of the 23rd and 24th of December, 1641. "That

the word Cavalier, not necessarily a term of reproach,

was unquestionably used in that sense on the occasion of

these tumults (probably to connect its French origin with

the un-English character of the defenders of the Queen

and her French papist adherents to whom it was chiefly

applied), appears from the fact that it is bandied about in

declarations alternately issued on the eve of the year by

the parliament and the king ; the latter speaking of it more

than once as a word much in disfavour. And, after the

standard on either side was unfurled — nay, when the battle

of Edgehill had been fought — Charles elaborately accuses

his antagonists, 'pretenders to peace and charity,' he calls

them ; charging them also with a 'hateful attempt to render

203

move he must make his purse lighter, w b was troublesome for weight, since S 1 ' Luis Divest saw him,

it being exhausted by the publick service, by his removals, banishm 18 , and many confinements, as

shall be further s d hereafter.

I do believe the usurpers had it for a necessary maxim to impoverise the Royal Party, pinching

them by considerable crooked serpentine ways last spoken of, and by their composition money

and untolerable taxes on their lands (whereof their rents must answer near to the half, having no

consideration of creditors; but that they might take the other half moiety, and so starve the family,

and also by tying them to all attendancies as afores d . This hardship (used to such as his Lo p ) must,

oblige them to borrow money, \v h cou'd not be had but on land and personal collateral security,

and if any of Oliver's men (who had the baggs) lent. What the other party needed, those huksters

(who, from robbers, were now become usurpers) for sure w d put them to expensive suits at law, as

I found in my own case ; for Colo. Barrowstons* (at one and the same time) sued myself and both

my bail kinsmen severally; or else if any of those pinched Cavaliers (so K. C h . the first's party

were called, as the parliament's were nicknamed Roundheads)3 s had money to spare, they wanted

33 Sir Luis Dives. — See p. 181, supra.

34 Colo. Barrowsttm. — Barrowston is a misprint for

Barrow's son. Colonel Robert Barrow succeeded colonel

Venables in command of the forces in northern Ulster.

In 1652, the government of the commonwealth let the

lands and house of Rosemount, the author's properly,

as a forfeited estate to this colonel Barrow, whose son

afterwards acted in the manner complained of in the text.

Colonel Barrow was quite a decided religionist, professing

anabaptist principles in opposition to the independents and

presbyterians. He signed the order in 1 651, for the re-

moval of such presbyterian ministers as could not submit

to the government of the commonwealth. This order was

soon afterwards relaxed; but Adair states that in 1654.,

while Barrow resided in Down (no doubt at Rosemount),

he was excited against the presbyterians by "the old

episcopal party, who, now when the power was out of

their own hands, to afflict the Presbytery, did insinuate on

those who had power, as they did now with the sectaries,

to incense them against the liberty the ministers had, and

against their discipline and public solemnities at com-

munions, &c. ; besides, suggesting that these their meetings

were dangerous to the state, and that they had therein

consultations for strengthening their own faction. This

so wrought with an Anabaptist governor, Colonel Barrow,

in the county of Down, that he became highly incensed,

and jealous of these meetings, and resolved to use his

endeavours to obtain an order for suppressing them."

Adair, however, goes on to state that an acquaintance

of Barrow having been present at the celebration of the

communion held by the presbyterians of Portaferry, re-

ported so favourably of them and their religious services,

that "Colonel Barrow, being a man pretending to much

piety, and though of Anabaptist principles, yet not of a

malicious disposition, from this time had more respect to

the ministers, and used not his interest to suppress their

liberty in the country." — True Narrative, pp. 180, 207,

208.

35 Cavaliers — Roundheads. — These terms were invariably

employed by the two parties towards each other in reproach

and contempt The royalists were regarded by their op-

ponents as a crew of atheists, papists, and voluptuaries ;

whilst the roundheads were believed by the cavaliers to be

simply a parcel of knaves, hypocrites, and traitors. The

latter were called roundheads because they cropped their hair

short, " dividing it," says the writer of the Life of Colonel

Hutchinson, p. ioo, "into so many little peaks, as was

something ridiculous to- behold." "The godly of those

days," he continues, "when the colonel embraced their

party would not allow him to be religious, because his

hair was not in their cut, nor his words in their phrase." —

Lingard, History of England, vol. viii. , p. 3, note.

William Lilly, in his Monarchy or No Monarchy in Eng-

land, part ii. , edition of 165 1, describes the roundheads

thus: — "Most of them were either such as had public

spirits, or lived a more religious life than the vulgar, and

were usually called Puritans, and had suffered under the

tyranny of the bishops. In the general they were very

honest men and well-meaning : some particular fools, or

others, perhaps, now and then, got in amongst them

greatly to the disadvantage of the more sober. They were

modest in their apparel, but not in their language ; they

had the hair of their heads very few of them longer than

their ears, whereupon it came to pass that those who usually

with their cries attended at Westminster, were by a

nickname called Roundheads." The contemptuous names

of cavalier and roundhead were first publicly used by the

two parties towards each other during the tumults and

riots of the 23rd and 24th of December, 1641. "That

the word Cavalier, not necessarily a term of reproach,

was unquestionably used in that sense on the occasion of

these tumults (probably to connect its French origin with

the un-English character of the defenders of the Queen

and her French papist adherents to whom it was chiefly

applied), appears from the fact that it is bandied about in

declarations alternately issued on the eve of the year by

the parliament and the king ; the latter speaking of it more

than once as a word much in disfavour. And, after the

standard on either side was unfurled — nay, when the battle

of Edgehill had been fought — Charles elaborately accuses

his antagonists, 'pretenders to peace and charity,' he calls

them ; charging them also with a 'hateful attempt to render

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Histories of Scottish families > Montgomery manuscripts > (217) Page 203 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/95235531 |

|---|

| Description | A selection of almost 400 printed items relating to the history of Scottish families, mostly dating from the 19th and early 20th centuries. Includes memoirs, genealogies and clan histories, with a few produced by emigrant families. The earliest family history goes back to AD 916. |

|---|