Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 13, Infant-Kant

(144) Page 134 - Insectivorous plants

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

134

INSECTIVOROUS PLANTS

INSECTIVOROUS PLANTS. Insectivorous or, as

they are sometimes more correctly termed, carnivorous

plants are, like the parasites, the climbers, or the succulents,

a physiological assemblage belonging to a number of

distinct natural orders. They agree in the extraordinary

habit of adding to the supplies of nitrogenous material

afforded them in common with other plants by the soil and

atmosphere, by the capture and consumption of insects and

other small animals. The curious and varied mechanical

arrangements by which these supplies of animal food, are

obtained, the ways and degrees in which they are utilized,

and the remarkable chemical, histological, and electrical

phenomena which accompany these processes of prehension

and utilization, can only be understood by a separate and

somewhat detailed examination of the leading orders and

genera. It is convenient to follow the order adopted by

Mr Darwin in his work on Insectivorous Plants (Lond.,

1875), to which our knowledge of the subject is mainly

due, incorporating, however, as far as possible the leading

observations of other writers on the subject. We must

preface this, however, by a brief summary of the facts of

taxonomy and distribution.

Taxonomy.—The best known and most important order

—the Droseracex—~is placed among the calycifloral exogens,

and has obvious affinities with the Saxifragacex. It

includes six genera—Byblis, Roridula, Drosera, Droso-

phyllum, Aldrovanda, and Dionxa, of which the last

three are monotypic, i.e., include only one species. The

curious pitcher-plant, Cephalotus follicularis, is usually

raised to the dignity of a separate natural order Cephalotese,

though Bentham and Hooker (Gen. Plant.) place it among

the Ribesiacex. The Sarraceniacex are thalamiflorals,

and contain the genera Sarracenia, Darlingtonia, Heliam-

phora, while the true pitcher plants or Nepenthacese,

consisting of the single large genus Nepenthes, are placed

near the Aristolochiacex among the Apetalx. Finally the

genera Pinguicula, Utricularia, Genlisea, and Polypom-

pholix belong to the gamopetalous order Utricidarix. Thus

all the four leading divisions of the exogenous plants are

represented by apparently unrelated orders; certain

affinities, however, are alleged between Droseracex,

Sarraceniacex, and Nepenthacex.

Distribution.—While the large genus Drosera has an all

but world-wide distribution, its congeners are restricted

to well-defined and

usually compara¬

tively small areas.

Thus Drosophyllum

occurs only in

Portugal and Mo¬

rocco, Byblis in

tropical Australia,

and, although Al¬

drovanda is found

in Queensland, in

Bengal, and in

Europe, a wide dis¬

tribution explained

by its aquatic habit,

Dionxais restricted

to a few localities

in North and South

Carolina, mainly

around Wilming¬

ton. Cephalotus

occurs only near

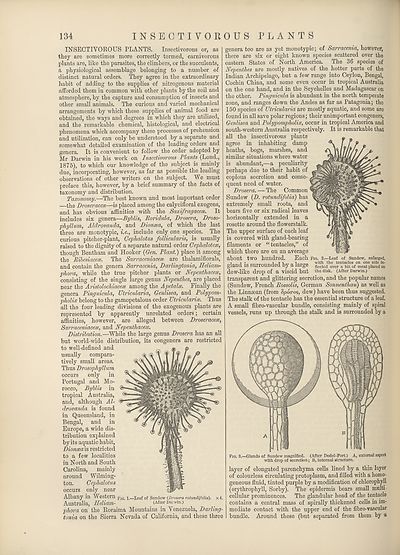

Albany in Western pia —Leaf of Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia). x4.

Australia, Heliam- (After Darwin.)

phora on the Roraima Mountains in Venezuela, Darling¬

tonia on the Sierra Nevada of California, and these three

genera too are as yet monotypic; of Sarracenia, however,

there are six or eight known species scattered over the

eastern States of North America. The 36 species of

Nepenthes are mostly natives of the hotter parts of the

Indian Archipelago, but a few range into Ceylon, Bengal,

Cochin China, and some even occur in tropical Australia

on the one hand, and in the Seychelles and Madagascar on

the other. Pinguicula is abundant in the north temperate

zone, and ranges down the Andes as far as Patagonia; the

150 species of Utricularia are mostly aquatic, and some are

found in all save polar regions; their unimportant congeners,

Genlisea and Polypompholix, occur in tropical America and

south-western Australia respectively. It is remarkable that

all the insectivorous plants

agree in inhabiting damp

heaths, bogs, marshes, and

similar situations where water

is abundant,—a peculiarity

perhaps due to their habit of

copious secretion and conse¬

quent need of water.

Drosera. — The Common

Sundew (D. rotundifolia) has

extremely small roots, and

bears five or six radical leaves

horizontally extended in a

rosette around the flowers talk.

The upper surface of each leaf

is covered with gland-bearing

filaments or “ tentacles,” of

which there are on an average

about two hundred. Each Fig. 2.—Leaf of Sundew, enlarged,

gland IS Surrounded by a large fleeted over a hit of meat placed on

dew-like drop of a viscid but the disk. (After Darwin.)

transparent and glittering secretion, and the popular names

(Sundew, French Bossolis, German Sonnenthau) as well as

the Linnsean (from Spocros, dew) have been thus suggested.

The stalk of the tentacle has the essential structure of a leaf.

A small fibro-vascular bundle, consisting mainly of spiral

vessels, runs up through the stalk and is surrounded by a

Fig. 3.—Glands of Sundew magnified. (After Dodel-Port.) A, external aspect

with drop of secretion; it, internal structure.

layer of elongated parenchyma cells lined by a thin layer

of colourless circulating protoplasm, and filled with a homo¬

geneous fluid, tinted purple by a modification of chlorophyll

(erythrophyll, Sorby). The epidermis bears small multi

cellular prominences. The glandular head of the tentacle

contains a central mass of spirally thickened cells in im¬

mediate contact with the upper end of the fibro-vascular

bundle. Around these (but separated from them by a

INSECTIVOROUS PLANTS

INSECTIVOROUS PLANTS. Insectivorous or, as

they are sometimes more correctly termed, carnivorous

plants are, like the parasites, the climbers, or the succulents,

a physiological assemblage belonging to a number of

distinct natural orders. They agree in the extraordinary

habit of adding to the supplies of nitrogenous material

afforded them in common with other plants by the soil and

atmosphere, by the capture and consumption of insects and

other small animals. The curious and varied mechanical

arrangements by which these supplies of animal food, are

obtained, the ways and degrees in which they are utilized,

and the remarkable chemical, histological, and electrical

phenomena which accompany these processes of prehension

and utilization, can only be understood by a separate and

somewhat detailed examination of the leading orders and

genera. It is convenient to follow the order adopted by

Mr Darwin in his work on Insectivorous Plants (Lond.,

1875), to which our knowledge of the subject is mainly

due, incorporating, however, as far as possible the leading

observations of other writers on the subject. We must

preface this, however, by a brief summary of the facts of

taxonomy and distribution.

Taxonomy.—The best known and most important order

—the Droseracex—~is placed among the calycifloral exogens,

and has obvious affinities with the Saxifragacex. It

includes six genera—Byblis, Roridula, Drosera, Droso-

phyllum, Aldrovanda, and Dionxa, of which the last

three are monotypic, i.e., include only one species. The

curious pitcher-plant, Cephalotus follicularis, is usually

raised to the dignity of a separate natural order Cephalotese,

though Bentham and Hooker (Gen. Plant.) place it among

the Ribesiacex. The Sarraceniacex are thalamiflorals,

and contain the genera Sarracenia, Darlingtonia, Heliam-

phora, while the true pitcher plants or Nepenthacese,

consisting of the single large genus Nepenthes, are placed

near the Aristolochiacex among the Apetalx. Finally the

genera Pinguicula, Utricularia, Genlisea, and Polypom-

pholix belong to the gamopetalous order Utricidarix. Thus

all the four leading divisions of the exogenous plants are

represented by apparently unrelated orders; certain

affinities, however, are alleged between Droseracex,

Sarraceniacex, and Nepenthacex.

Distribution.—While the large genus Drosera has an all

but world-wide distribution, its congeners are restricted

to well-defined and

usually compara¬

tively small areas.

Thus Drosophyllum

occurs only in

Portugal and Mo¬

rocco, Byblis in

tropical Australia,

and, although Al¬

drovanda is found

in Queensland, in

Bengal, and in

Europe, a wide dis¬

tribution explained

by its aquatic habit,

Dionxais restricted

to a few localities

in North and South

Carolina, mainly

around Wilming¬

ton. Cephalotus

occurs only near

Albany in Western pia —Leaf of Sundew (Drosera rotundifolia). x4.

Australia, Heliam- (After Darwin.)

phora on the Roraima Mountains in Venezuela, Darling¬

tonia on the Sierra Nevada of California, and these three

genera too are as yet monotypic; of Sarracenia, however,

there are six or eight known species scattered over the

eastern States of North America. The 36 species of

Nepenthes are mostly natives of the hotter parts of the

Indian Archipelago, but a few range into Ceylon, Bengal,

Cochin China, and some even occur in tropical Australia

on the one hand, and in the Seychelles and Madagascar on

the other. Pinguicula is abundant in the north temperate

zone, and ranges down the Andes as far as Patagonia; the

150 species of Utricularia are mostly aquatic, and some are

found in all save polar regions; their unimportant congeners,

Genlisea and Polypompholix, occur in tropical America and

south-western Australia respectively. It is remarkable that

all the insectivorous plants

agree in inhabiting damp

heaths, bogs, marshes, and

similar situations where water

is abundant,—a peculiarity

perhaps due to their habit of

copious secretion and conse¬

quent need of water.

Drosera. — The Common

Sundew (D. rotundifolia) has

extremely small roots, and

bears five or six radical leaves

horizontally extended in a

rosette around the flowers talk.

The upper surface of each leaf

is covered with gland-bearing

filaments or “ tentacles,” of

which there are on an average

about two hundred. Each Fig. 2.—Leaf of Sundew, enlarged,

gland IS Surrounded by a large fleeted over a hit of meat placed on

dew-like drop of a viscid but the disk. (After Darwin.)

transparent and glittering secretion, and the popular names

(Sundew, French Bossolis, German Sonnenthau) as well as

the Linnsean (from Spocros, dew) have been thus suggested.

The stalk of the tentacle has the essential structure of a leaf.

A small fibro-vascular bundle, consisting mainly of spiral

vessels, runs up through the stalk and is surrounded by a

Fig. 3.—Glands of Sundew magnified. (After Dodel-Port.) A, external aspect

with drop of secretion; it, internal structure.

layer of elongated parenchyma cells lined by a thin layer

of colourless circulating protoplasm, and filled with a homo¬

geneous fluid, tinted purple by a modification of chlorophyll

(erythrophyll, Sorby). The epidermis bears small multi

cellular prominences. The glandular head of the tentacle

contains a central mass of spirally thickened cells in im¬

mediate contact with the upper end of the fibro-vascular

bundle. Around these (but separated from them by a

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 13, Infant-Kant > (144) Page 134 - Insectivorous plants |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/194287151 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|