Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Anatomy-Astronomy

(199) Page 191

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

ANIMAL KINGDOM.

191

Animal Let us here note, that M. Desmoulins, in the 2d edi-

Kingdom. tion of Dr Magendie’s Physiology (1825), has exhibited a

system in which the principles of Cuvier and De Blain-

ville are joined in one.

A learned and ingenious Scotsman, Mr William Sharpe

Macleay, is the author of several profound and original

views in natural history. The unbroken and continuous

succession, or linear series, in which systematic writers

had previously regarded the objects of their contempla¬

tion, was first deviated from by Lamarck, who, in his sup¬

plement to the first volume of his Animaux sans Verte-

breS) presented the Invertebrata in a double subramose

series, consisting of articulated and inarticulated animals.

The following are the principal bases of Mr Macleay’s

system.1

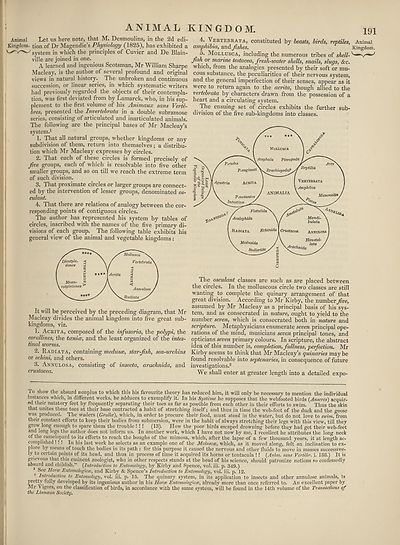

1. That all natural groups, whether kingdoms or any

subdivision of them, return into themselves; a distribu¬

tion which Mr Macleay expresses by circles.

2. That each of these circles is formed precisely of

Jive groups, each of which is resolvable into five other

smaller groups, and so on till we reach the extreme term

of such division.

3. That proximate circles or larger groups are connect¬

ed by the intervention of lesser groups, denominated os¬

culant.

4. That there are relations of analogy between the cor¬

responding points of contiguous circles.

The author has represented his system by tables of

circles, inscribed with the names of the five primary di¬

visions of each group. The following table exhibits his

general view of the animal and vegetable kingdoms:

It will be perceived by the preceding diagram, that Mr

Macleay divides the animal kingdom into five great sub¬

kingdoms, viz.

1. Aciuta, composed of the infusoria, the polypi, the

corallines, the tcenice, and the least organized of the intes¬

tinal worms.

2. Radiata, containing medusae, star-fish, sea-urchins

or echini, and others.

3. Annulosa, consisting of insecta, arachnida, and

Crustacea.

4. Yertebrata, constituted by beasts, birds, reptiles, Animal

amphibia, and fishes. Kingdom.

5. Mollusca, including the numerous tribes of shell-

fish or marine testacea, fresh-water shells, snails, slugs, &c.

which, from the analogies presented by their soft or mu¬

cous substance, the peculiarities of their nervous system,

and the general imperfection of their senses, appear as it

were to return again to the acrita, though allied to the

vertebrata by characters drawn from the possession of a

heart and a circulating system.

The ensuing set of circles exhibits the further sub¬

division of the five sub-kingdoms into classes.

The osculant classes are such as are placed between

the circles. In the molluscous circle two classes are still

wanting to complete the quinary arrangement of that

great division. According to Mr Kirby, the number five,

assumed by Mr Macleay as a principal basis of his sys¬

tem, and as consecrated in nature, ought to yield to the

number seven, which is consecrated both in nature and

scripture. Metaphysicians enumerate seven principal ope¬

rations of the mind, musicians seven principal tones, and

opticians seven primary colours. In scripture, the abstract

idea of this number is, completion, fullness, perfection. Mr

Kirby seems to think that Mr Macleay’s quinaries may be

found resolvable into septenaries, in consequence of future

investigations.2

We shall enter at greater length into a detailed expo-

T° sll0w the absurd nonplus to which this his favourite theory has reduced him, it will only be necessary to mention the individual

instances which, in different works, he adduces to exemplify it. In his Systeme he supposes that the webfooted birds (Anseres) acquir¬

ed their natatory feet by frequently separating their toes as far as possible from each other in their efforts to swim. Thus the skin

that unites these toes at their base contracted a habit of stretching itself; and thus in time the web-foot of the duck and the goose

was produced. The waders (Grallce), which, in order to procure their food, must stand in the water, but do not love to swim, {rom

their constant efforts to keep their bodies from submersion, were in the habit of always stretching their legs with this view, till they

grew long enough to spare them the trouble ! ! ! (13). How the poor birds escaped drowning before they had got their web-feet

and long legs the author does not inform us. In another work, which I have not now by me, I recollect he attributes the long neck

of the camelopard to its efforts to reach the boughs of the mimosa, which, after the lapse of a few thousand years, it at length ac¬

complished ! ! ! In his last work he selects as an example one of the Moluscx, which, as it moved along, felt an inclination to ex-

plore by means, of touch the bodies in its path : for this purpose it caused the nervous and other fluids to move in masses successive-

ly to certain points of its head, and thus in process of time it acquired its horns or tentacula !! (Anim. sans Vertebr. i. 188.) It is

grievous that this eminent zoologist, who in other respects stands at the head of his science, should patronize notions so confessedly

absurd and childish.” {Introduction to Entomology, by Kirby and Spence, vol. iii. p. 349.)

^ See Horae Entomologicoc, and Kirby & Spence’s Introduction to Entomology, vol. iii. p. 12.

Introduction to Entomology, vol. iii. p. 15. The quinary system, in its application to insects and other annulose animals, is

pretty fully developed by its ingenious author in his Horae Entomologicce, already more than once referred to. An excellent paper by

Mr Vigors, on the classification of birds, in accordance with the same system, will be found in the 14th volume of the Transactions of

the Linncean Society.

191

Animal Let us here note, that M. Desmoulins, in the 2d edi-

Kingdom. tion of Dr Magendie’s Physiology (1825), has exhibited a

system in which the principles of Cuvier and De Blain-

ville are joined in one.

A learned and ingenious Scotsman, Mr William Sharpe

Macleay, is the author of several profound and original

views in natural history. The unbroken and continuous

succession, or linear series, in which systematic writers

had previously regarded the objects of their contempla¬

tion, was first deviated from by Lamarck, who, in his sup¬

plement to the first volume of his Animaux sans Verte-

breS) presented the Invertebrata in a double subramose

series, consisting of articulated and inarticulated animals.

The following are the principal bases of Mr Macleay’s

system.1

1. That all natural groups, whether kingdoms or any

subdivision of them, return into themselves; a distribu¬

tion which Mr Macleay expresses by circles.

2. That each of these circles is formed precisely of

Jive groups, each of which is resolvable into five other

smaller groups, and so on till we reach the extreme term

of such division.

3. That proximate circles or larger groups are connect¬

ed by the intervention of lesser groups, denominated os¬

culant.

4. That there are relations of analogy between the cor¬

responding points of contiguous circles.

The author has represented his system by tables of

circles, inscribed with the names of the five primary di¬

visions of each group. The following table exhibits his

general view of the animal and vegetable kingdoms:

It will be perceived by the preceding diagram, that Mr

Macleay divides the animal kingdom into five great sub¬

kingdoms, viz.

1. Aciuta, composed of the infusoria, the polypi, the

corallines, the tcenice, and the least organized of the intes¬

tinal worms.

2. Radiata, containing medusae, star-fish, sea-urchins

or echini, and others.

3. Annulosa, consisting of insecta, arachnida, and

Crustacea.

4. Yertebrata, constituted by beasts, birds, reptiles, Animal

amphibia, and fishes. Kingdom.

5. Mollusca, including the numerous tribes of shell-

fish or marine testacea, fresh-water shells, snails, slugs, &c.

which, from the analogies presented by their soft or mu¬

cous substance, the peculiarities of their nervous system,

and the general imperfection of their senses, appear as it

were to return again to the acrita, though allied to the

vertebrata by characters drawn from the possession of a

heart and a circulating system.

The ensuing set of circles exhibits the further sub¬

division of the five sub-kingdoms into classes.

The osculant classes are such as are placed between

the circles. In the molluscous circle two classes are still

wanting to complete the quinary arrangement of that

great division. According to Mr Kirby, the number five,

assumed by Mr Macleay as a principal basis of his sys¬

tem, and as consecrated in nature, ought to yield to the

number seven, which is consecrated both in nature and

scripture. Metaphysicians enumerate seven principal ope¬

rations of the mind, musicians seven principal tones, and

opticians seven primary colours. In scripture, the abstract

idea of this number is, completion, fullness, perfection. Mr

Kirby seems to think that Mr Macleay’s quinaries may be

found resolvable into septenaries, in consequence of future

investigations.2

We shall enter at greater length into a detailed expo-

T° sll0w the absurd nonplus to which this his favourite theory has reduced him, it will only be necessary to mention the individual

instances which, in different works, he adduces to exemplify it. In his Systeme he supposes that the webfooted birds (Anseres) acquir¬

ed their natatory feet by frequently separating their toes as far as possible from each other in their efforts to swim. Thus the skin

that unites these toes at their base contracted a habit of stretching itself; and thus in time the web-foot of the duck and the goose

was produced. The waders (Grallce), which, in order to procure their food, must stand in the water, but do not love to swim, {rom

their constant efforts to keep their bodies from submersion, were in the habit of always stretching their legs with this view, till they

grew long enough to spare them the trouble ! ! ! (13). How the poor birds escaped drowning before they had got their web-feet

and long legs the author does not inform us. In another work, which I have not now by me, I recollect he attributes the long neck

of the camelopard to its efforts to reach the boughs of the mimosa, which, after the lapse of a few thousand years, it at length ac¬

complished ! ! ! In his last work he selects as an example one of the Moluscx, which, as it moved along, felt an inclination to ex-

plore by means, of touch the bodies in its path : for this purpose it caused the nervous and other fluids to move in masses successive-

ly to certain points of its head, and thus in process of time it acquired its horns or tentacula !! (Anim. sans Vertebr. i. 188.) It is

grievous that this eminent zoologist, who in other respects stands at the head of his science, should patronize notions so confessedly

absurd and childish.” {Introduction to Entomology, by Kirby and Spence, vol. iii. p. 349.)

^ See Horae Entomologicoc, and Kirby & Spence’s Introduction to Entomology, vol. iii. p. 12.

Introduction to Entomology, vol. iii. p. 15. The quinary system, in its application to insects and other annulose animals, is

pretty fully developed by its ingenious author in his Horae Entomologicce, already more than once referred to. An excellent paper by

Mr Vigors, on the classification of birds, in accordance with the same system, will be found in the 14th volume of the Transactions of

the Linncean Society.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Anatomy-Astronomy > (199) Page 191 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193759935 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.16 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|