Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Anatomy-Astronomy

(84) Page 76

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

76

ANATOMY.

Compara¬

tive

Anatomy.

in the Rodentia, it is there shorter; and the arrangement

is wanting in the other tribes. The size of the transverse

processes indicates the strength of the loins,—a fact

which is evinced especially in the instance of the horse,

porpoise, &c.

Sacral ver- The number of sacral vertebrae is still more various,

tebrae. even jn the species of the same genus. Thus, while in

several of the ape genus, in the lori, in the vampyre bat,

the colugo (galeopithecus), the coati, and two of the

didelphis, there is one sacral vertebra only, most of the

apes have sacra consisting of 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 pieces ; the

majority of other animals have 3 sacral vertebrae; the

hedgehog, porcupine, guinea pig, paca, hare, tiger, several

of the murine genus, the ant-eater, rhinoceros, camel, dro¬

medary, chamois, goat, sheep, and ox, have 4; the ele¬

phant has 5; the Ai 6; the Uhau 7; and in the mole,

white bear, and quagga, they also amount to 7. The fre¬

quency of the three sacral vertebrae in the lower animals

shows that Galen, who ascribes only 3 to the human sub¬

ject, must have derived this inference from the former.

These vertebrae are in the mammalia narrower than in

man, and their direction forms with the spine, instead of

receding backwards, a straight line ; an arrangement evi¬

dently connected with the horizontal position of the for¬

mer. The shape of the sacrum in the lower mammals is

that of an elongated triangle ; and it is further remarkable,

that in those species which occasionally assume the erect

attitude on the hind leg, as apes, bears, and sloths, the

width of the sacrum is proportionally greater. The sa¬

cral spines, which are short in man and the ape, become

longer in the Zooph ag a, and form a continuous ridge in the

rhinoceros, most ruminants, and especially in the mole. In

the vampyre bat the sacrum forms a long compressed

cone, the extremity of which is united to the ischial tu¬

berosities, without sustaining a coccyx. The seal has two

sacral bones ; but the Cetacea, e. g. the dolphin and por¬

poise, are void both of sacrum and coccyx.

The coccygeal bones constitute the tail of the lower

animals, and in many instances they are extremely nume¬

rous. The smallest number is 3, which is that of the

magot (simia, sylvanus, pithecus, et inuus) or Barbary ape ;

and the greatest yet known is that of the ant-eater, in

which they amount to 40, and the long-tailed manis, in

which they amount to 45. Next to these may be placed

that of the coai'ta 32, the baboon 31, the phalanger {di¬

delphis orientalis) 30, the marmoset {didelphis marina) 29,

the pangolin 28, the silky monkey {simia rosalia) and

black rat 26, the weeping monkey and howling ape 25 ; the

panther, mouse, dormouse, and elephant, 24; the lion,

beaver, water-rat, Norway rat, and field-rat, 23 ; the flying-

cat, puma, cat, dog, marmot, and rhinoceros, 22; the

otter, 21; the Chinese monkey, raccoon, civet, hare, and

rabbit, 20; the tiger and wolf, 19; the macauco, glutton,

marten, fat dormouse, dromedary, giraffe, and quagga, 18;

the tarsier, shrew, camel, and horse, 17 ; and other genera

and species, without any determinate order, descending

so low as to 9, 8, 7, 6, and 4. The quilled duckbill {echidna,

ornithorhyncus hystrix) has only 12 caudal vertebrae, while

the common one {ornithorhyncus paradoxus) has at least

20. The gibbon and vampyre bat are the only mammifer-

ous animals, excepting the Cetacea, in which there are

no coccygeal bones. It sometimes happens that a monkey

or opossum loses a portion of its tail, when the truncated

end is converted into a knotty excrescence, sometimes

carious, always different from the taper point of the last

coccygeal vertebra; and in this case it is difficult to de¬

termine the exact species.

In the Cetacea, in which the absence of pelvis affords

no mark to distinguish the lower vertebrae into lumbar,

sacral, and coccygeal, those below the dorsal may be re¬

el. Lc

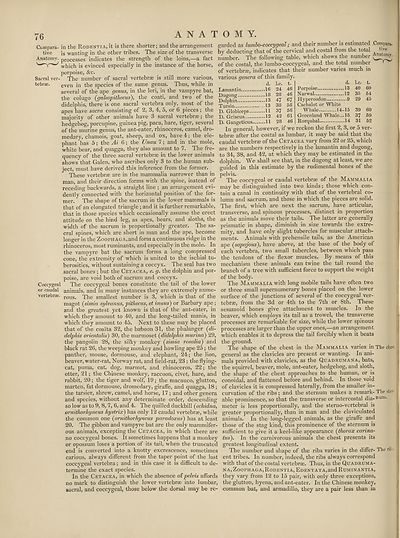

Lamantin 16 24

Dugong 18 28

Dolphin 13 47

Tursio .13 38

D. Globiceps 11 37

D. Griseus 12 42

D. Gangeticus 11 28

Coccygeal

or caudal

vertebrae.

garded as lumbo-coccygeal; and their number is estimated Compara.

by deducting that of the cervical and costal from the total hve

number. The following table, which shows the number

of the costal, the lumbo-coccygeal, and the total number

of vertebrae, indicates that their number varies much in

various genera of this family.

t. d. l.c. t.

46 Porpoise 13 40 60

46 Narwal 12 35 54

67 Hyperoodon 9 29 45

58 Cachalot or White

56 Whale 14-15 39 60

61 Greenland Whale... 15 37 59

46 Rorquhal 14 31 52

In general, however, if we reckon the first 2, 3, or 5 ver¬

tebrae after the costal as lumbar, it may be said that the

caudal vertebrae of the Cetacea vary from 22 or 25, which

are the numbers respectively in the lamantin and dugong,

to 34, 38, and 42, at which they may be estimated in the

dolphin. We shall see that, in the dugong at least, we are

guided in this estimate by the rudimental bones of the

pelvis.

The coccygeal or caudal vertebrae of the Mammalia

may be distinguished into two kinds; those which con¬

tain a canal in continuity with that of the vertebral co¬

lumn and sacrum, and those in which the pieces are solid.

The first, which are next the sacrum, have articular,

transverse, and spinous processes, distinct in proportion

as the animals move their tails. The latter are generally

prismatic in shape, diminish in size towards the extre¬

mity, and have only slight tubercles for muscular attach¬

ments. Animals with prehensile tails, as the American

ape {sapajous), have above, at the base of the body of

each vertebra, two small tubercles, between which pass

the tendons of the flexor muscles. By means of this

mechanism these animals can twine the tail round the

branch of a tree with sufficient force to support the weight

of the body.

The Mammalia with long mobile tails have often two

or three small supernumerary bones placed on the lower

surface of the junctions of several of the coccygeal ver-

tebrae, from the 3d or 4th to the 7th or 8th. These

sesamoid bones give attachment to muscles. In the

beaver, which employs its tail as a trowel, the transverse

processes are remarkable for size, while the lower spinous

processes are larger than the upper ones,—an arrangement

which enables it to depress the tail forcibly when it beats

the ground.

The shape of the chest in the Mammalia varies in The chest

general as the clavicles are present or wanting. In ani¬

mals provided with clavicles, as the Quadrumana, bats,

the squirrel, beaver, mole, ant-eater, hedgehog, and sloth,

the shape of the chest approaches to the human, or is

conoidal, and flattened before and behind. In those void

of clavicles it is compressed laterally, from the smaller in¬

curvation of the ribs ; and the sternum makes a remark- The ster-

able prominence, so that the transverse or intercostal dia-nuni-

meter is less proportionally, and the sterno-vertebral is

greater proportionally, than in man and the claviculated

animals. In the long-legged animals, as the giraffe and

those of the stag kind, this prominence of the sternum is

sufficient to give it a keel-like appearance {thorax carina-

tus). In the carnivorous animals the chest presents its

greatest longitudinal extent.

The number and shape of the ribs varies in the differ- The ril

ent tribes. In number, indeed, the ribs always correspond

with that of the costal vertebrae. Thus, in the Quadruma¬

na, Zoophaga, Rodentia, Edentata,and Ruminantia,

they vary from 12 to 15 pair, with only three exceptions,

the glutton, hyena, and ant-eater. In the Chinese monkey,

common bat, and armadillo, they are a pair less than in

ANATOMY.

Compara¬

tive

Anatomy.

in the Rodentia, it is there shorter; and the arrangement

is wanting in the other tribes. The size of the transverse

processes indicates the strength of the loins,—a fact

which is evinced especially in the instance of the horse,

porpoise, &c.

Sacral ver- The number of sacral vertebrae is still more various,

tebrae. even jn the species of the same genus. Thus, while in

several of the ape genus, in the lori, in the vampyre bat,

the colugo (galeopithecus), the coati, and two of the

didelphis, there is one sacral vertebra only, most of the

apes have sacra consisting of 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 pieces ; the

majority of other animals have 3 sacral vertebrae; the

hedgehog, porcupine, guinea pig, paca, hare, tiger, several

of the murine genus, the ant-eater, rhinoceros, camel, dro¬

medary, chamois, goat, sheep, and ox, have 4; the ele¬

phant has 5; the Ai 6; the Uhau 7; and in the mole,

white bear, and quagga, they also amount to 7. The fre¬

quency of the three sacral vertebrae in the lower animals

shows that Galen, who ascribes only 3 to the human sub¬

ject, must have derived this inference from the former.

These vertebrae are in the mammalia narrower than in

man, and their direction forms with the spine, instead of

receding backwards, a straight line ; an arrangement evi¬

dently connected with the horizontal position of the for¬

mer. The shape of the sacrum in the lower mammals is

that of an elongated triangle ; and it is further remarkable,

that in those species which occasionally assume the erect

attitude on the hind leg, as apes, bears, and sloths, the

width of the sacrum is proportionally greater. The sa¬

cral spines, which are short in man and the ape, become

longer in the Zooph ag a, and form a continuous ridge in the

rhinoceros, most ruminants, and especially in the mole. In

the vampyre bat the sacrum forms a long compressed

cone, the extremity of which is united to the ischial tu¬

berosities, without sustaining a coccyx. The seal has two

sacral bones ; but the Cetacea, e. g. the dolphin and por¬

poise, are void both of sacrum and coccyx.

The coccygeal bones constitute the tail of the lower

animals, and in many instances they are extremely nume¬

rous. The smallest number is 3, which is that of the

magot (simia, sylvanus, pithecus, et inuus) or Barbary ape ;

and the greatest yet known is that of the ant-eater, in

which they amount to 40, and the long-tailed manis, in

which they amount to 45. Next to these may be placed

that of the coai'ta 32, the baboon 31, the phalanger {di¬

delphis orientalis) 30, the marmoset {didelphis marina) 29,

the pangolin 28, the silky monkey {simia rosalia) and

black rat 26, the weeping monkey and howling ape 25 ; the

panther, mouse, dormouse, and elephant, 24; the lion,

beaver, water-rat, Norway rat, and field-rat, 23 ; the flying-

cat, puma, cat, dog, marmot, and rhinoceros, 22; the

otter, 21; the Chinese monkey, raccoon, civet, hare, and

rabbit, 20; the tiger and wolf, 19; the macauco, glutton,

marten, fat dormouse, dromedary, giraffe, and quagga, 18;

the tarsier, shrew, camel, and horse, 17 ; and other genera

and species, without any determinate order, descending

so low as to 9, 8, 7, 6, and 4. The quilled duckbill {echidna,

ornithorhyncus hystrix) has only 12 caudal vertebrae, while

the common one {ornithorhyncus paradoxus) has at least

20. The gibbon and vampyre bat are the only mammifer-

ous animals, excepting the Cetacea, in which there are

no coccygeal bones. It sometimes happens that a monkey

or opossum loses a portion of its tail, when the truncated

end is converted into a knotty excrescence, sometimes

carious, always different from the taper point of the last

coccygeal vertebra; and in this case it is difficult to de¬

termine the exact species.

In the Cetacea, in which the absence of pelvis affords

no mark to distinguish the lower vertebrae into lumbar,

sacral, and coccygeal, those below the dorsal may be re¬

el. Lc

Lamantin 16 24

Dugong 18 28

Dolphin 13 47

Tursio .13 38

D. Globiceps 11 37

D. Griseus 12 42

D. Gangeticus 11 28

Coccygeal

or caudal

vertebrae.

garded as lumbo-coccygeal; and their number is estimated Compara.

by deducting that of the cervical and costal from the total hve

number. The following table, which shows the number

of the costal, the lumbo-coccygeal, and the total number

of vertebrae, indicates that their number varies much in

various genera of this family.

t. d. l.c. t.

46 Porpoise 13 40 60

46 Narwal 12 35 54

67 Hyperoodon 9 29 45

58 Cachalot or White

56 Whale 14-15 39 60

61 Greenland Whale... 15 37 59

46 Rorquhal 14 31 52

In general, however, if we reckon the first 2, 3, or 5 ver¬

tebrae after the costal as lumbar, it may be said that the

caudal vertebrae of the Cetacea vary from 22 or 25, which

are the numbers respectively in the lamantin and dugong,

to 34, 38, and 42, at which they may be estimated in the

dolphin. We shall see that, in the dugong at least, we are

guided in this estimate by the rudimental bones of the

pelvis.

The coccygeal or caudal vertebrae of the Mammalia

may be distinguished into two kinds; those which con¬

tain a canal in continuity with that of the vertebral co¬

lumn and sacrum, and those in which the pieces are solid.

The first, which are next the sacrum, have articular,

transverse, and spinous processes, distinct in proportion

as the animals move their tails. The latter are generally

prismatic in shape, diminish in size towards the extre¬

mity, and have only slight tubercles for muscular attach¬

ments. Animals with prehensile tails, as the American

ape {sapajous), have above, at the base of the body of

each vertebra, two small tubercles, between which pass

the tendons of the flexor muscles. By means of this

mechanism these animals can twine the tail round the

branch of a tree with sufficient force to support the weight

of the body.

The Mammalia with long mobile tails have often two

or three small supernumerary bones placed on the lower

surface of the junctions of several of the coccygeal ver-

tebrae, from the 3d or 4th to the 7th or 8th. These

sesamoid bones give attachment to muscles. In the

beaver, which employs its tail as a trowel, the transverse

processes are remarkable for size, while the lower spinous

processes are larger than the upper ones,—an arrangement

which enables it to depress the tail forcibly when it beats

the ground.

The shape of the chest in the Mammalia varies in The chest

general as the clavicles are present or wanting. In ani¬

mals provided with clavicles, as the Quadrumana, bats,

the squirrel, beaver, mole, ant-eater, hedgehog, and sloth,

the shape of the chest approaches to the human, or is

conoidal, and flattened before and behind. In those void

of clavicles it is compressed laterally, from the smaller in¬

curvation of the ribs ; and the sternum makes a remark- The ster-

able prominence, so that the transverse or intercostal dia-nuni-

meter is less proportionally, and the sterno-vertebral is

greater proportionally, than in man and the claviculated

animals. In the long-legged animals, as the giraffe and

those of the stag kind, this prominence of the sternum is

sufficient to give it a keel-like appearance {thorax carina-

tus). In the carnivorous animals the chest presents its

greatest longitudinal extent.

The number and shape of the ribs varies in the differ- The ril

ent tribes. In number, indeed, the ribs always correspond

with that of the costal vertebrae. Thus, in the Quadruma¬

na, Zoophaga, Rodentia, Edentata,and Ruminantia,

they vary from 12 to 15 pair, with only three exceptions,

the glutton, hyena, and ant-eater. In the Chinese monkey,

common bat, and armadillo, they are a pair less than in

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Anatomy-Astronomy > (84) Page 76 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193758440 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.16 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|