Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Athens-BOI

(647) Page 635

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

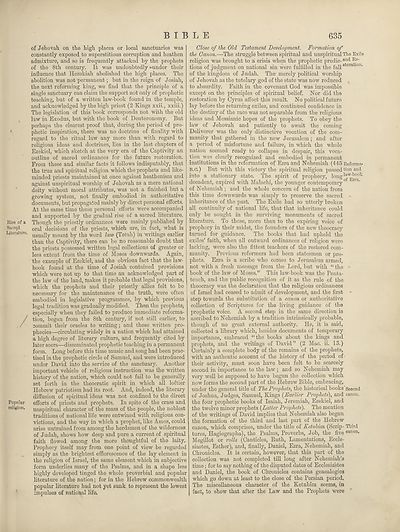

BIBLE

Rise of a

Sacred

Literature.

Popular

religion.

635

of Jehovah, on the high places or local sanctuaries was

constantly exposed to superstitious corruption and heathen

admixture, and so is frequently attacked by the prophets

of the 8th century. It was undoubtedly •under their

influence that Hezekiah abolished the high places. The

abolition was not permanent; but in the reign of Josiah,

the next reforming king, we find that the principle of a

single sanctuary can claim the support not only of prophetic

teaching, but of a written law-book found in the temple,

and acknowledged by the high priest (2 Kings xxii., xxiii.)

The legislation of this book corresponds not with the old

law in Exodus, but with the book of Deuteronomy. But

perhaps the clearest proof that, during the period of pro¬

phetic inspiration, there was no doctrine of finality with

regard to the ritual law any more than with regard to

religious ideas and doctrines, lies in the last chapters of

Ezekiel, which sketch at the very era of the Captivity an

outline of sacred ordinances for the future restoration.

From these and similar facts it follows indisputably, that

the true and spiritual religion which the prophets and like-

minded priests maintained at once against heathenism and

against unspiritual worship of Jehovah as a mere national

deity without moral attributes, was not a finished but a

growing system, not finally embodied in authoritative

documents, but propagated mainly by direct personal efforts.

A.t the same time these personal efforts were accompanied

and supported by the gradual rise of a sacred literature.

Though the priestly ordinances were mainly published by

oral decisions of the priests, which are, in fact, wbat is

usually meant by the word law (Torah) in writings earlier

than the Captivity, there can be no reasonable doubt that

the priests possessed written legal collections of greater or

less extent from the time of Moses downwards. Again,

the example of Ezekiel, and the obvious fact that the law¬

book found at the time of Josiah contained provisions

which were not up to that time an acknowledged part of

the law of the land, makes it probable that legal provisions,

which the prophets and their priestly allies felt to be

necessary for the maintenance of the truth, were often

embodied in legislative programmes, by which previous

legal tradition was gradually modified. Then the prophetsj

especially when they failed to produce immediate reforma¬

tion, began from the 8th century, if not still earlier, to-

commit their oracles to writing; and these written pro¬

phecies—circulating widely in a nation which had attained

a high degree of literary culture, and frequently cited by

later seers—disseminated prophetic teaching in a permanent

form. Long before this time music and song had been prac¬

tised in the prophetic circle of Samuel, and were introduced

under David into the service of the sanctuary. Another

important vehicle of religious instruction was the written

history of the nation, which could not fail to be generally

set forth in the theocratic spirit in which all loftier

Hebrew patriotism had its root. And, indeed, the literary

diffusion of spiritual ideas was not confined to the direct

efforts of priests and prophets. In spite of the crass and

unspiritual character of the mass of the people, the noblest

traditions of national life were entwined with religious con¬

victions, and the way in which a prophet, like Amos, could

arise untrained from among the herdsmen of the wilderness

of Judah, shows how deep and pure a current of spiritual

faith flowed among the more thoughtful of the laity.

Prophecy itself may from one point of view be regarded

simply as the brightest efflorescence of the lay element in

the religion of Israel, the same element which in subjective

form underlies many of the Psalms, and in a shape less

highly developed tinged the whole proverbial and popular

literature of the nation; for in the Hebrew commonwealth

popular literature had not yet sunk to represent the lowest

impulses of national life.

Close of the Old Testament Development. Formation of

the Canon.—The struggle between spiritual and unspiritual The Exile

religion was brought to a crisis when the prophetic predic-an(i ®e‘

tions of judgment on national sin were fulfilled in the fairstora lon'

of the kingdom of Judah. The' merely political worship

of Jehovah as the tutelary god of the state was now reduced

to absurdity. Faith in the covenant God was impossible

except on the principles of spiritual belief. Nor did the

restoration by Cyrus affect this result. No political future

lay before the returning exiles, and continued confidence in

the destiny of the race was not separable from the religious

ideas and Messianic hopes of the prophets. To obey the

law of Jehovah and patiently to await the coming

Deliverer was the only distinctive vocation of the com¬

munity that gathered in the new Jerusalem; and after

a period of misfortune and failure, in which the whole

nation seemed ready to collapse in despair, this voca¬

tion was dearly recognized and embodied in permanent

institutions in the reformation of'Ezra and Nehemiah (445 Roforma-

B.c.) But with this victory the spiritual religion passed tion and

into a stationary state. The spirit of prophecy, long^',^”k

decadent, expired with Malachi, the younger contemporary0 zra‘

of Nehemiah ; and the whole concern of the nation from

this time downwards was simply to preserve the sacred -

inheritance of the past. The Exile had so utterly broken

all continuity of national life, that that inheritance could

only be sought in the surviving monuments of sacred

literature. To these, more than to the expiring voice of

prophecy in their midst, the founders of the new theocracy

turned for guidance. The books that had upheld the

exiles’ faith, when all outward ordinances of religion were

lacking, were also the fittest teachers of the restored com¬

munity. Previous reformers had been statesmen or pro¬

phets. Ezra is a scribe who comes to Jerusalem armed,

not with a fresh message from the Lord, but with “the '

book of the law of Moses.” This law-book was the Penta¬

teuch, and the public recognition of it as the rule of the

theocracy was the declaration that the religious ordinances

of Israel had ceased to admit of development, and the first

step towards the substitution of a canon or authoritative

collection of Scriptures for the living guidance of the

prophetic voice. A second step in the same direction is

ascribed to Nehemiah by a tradition intrinsically probable,

though of no great external authority. He, it is said,

collected a library which, besides documents of temporary

importance, embraced “the books about the kings and

prophets, and the writings of David" (2 Mac. ii. 13.)

Certainly a complete body of the remains of the prophets,

with an authentic account of the history of the period of

their activity, must soon have been felt to be scarcely

second in importance to the law; and so Nehemiah may

very well be supposed to have begun the collection which

now forms the second part of the Hebrew Bible, embracing,

under the general title of The Prophets, the historical books Second

of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings (Earlier Prophets), and canon,

the four prophetic books of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and

the twelve minor prophets (Latter Prophets). The mention

of the writings of David implies that Nehemiah also began

the formation of the third and last part of the Hebrew

canon, which comprises, under the title of Ketubim (Scrip- Third

tures, Hagiographa), the Psalms, Proverbs, Job, the five cari(m-

Megillot or rolls (Canticles, Ruth, Lamentations, Eccle¬

siastes, Esther), and, finally, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, and

Chronicles. It is certain, however, that this part of the

collection was not completed till long after Nehemiah’s

time; for to say nothing of the disputed dates of Ecclesiastes

and Daniel, the book of Chronicles contains genealogies

which go down at least to the close of the Persian period.

The miscellaneous character of the Ketubim seems, in

fact, to show that after the Law and the Prophets were

Rise of a

Sacred

Literature.

Popular

religion.

635

of Jehovah, on the high places or local sanctuaries was

constantly exposed to superstitious corruption and heathen

admixture, and so is frequently attacked by the prophets

of the 8th century. It was undoubtedly •under their

influence that Hezekiah abolished the high places. The

abolition was not permanent; but in the reign of Josiah,

the next reforming king, we find that the principle of a

single sanctuary can claim the support not only of prophetic

teaching, but of a written law-book found in the temple,

and acknowledged by the high priest (2 Kings xxii., xxiii.)

The legislation of this book corresponds not with the old

law in Exodus, but with the book of Deuteronomy. But

perhaps the clearest proof that, during the period of pro¬

phetic inspiration, there was no doctrine of finality with

regard to the ritual law any more than with regard to

religious ideas and doctrines, lies in the last chapters of

Ezekiel, which sketch at the very era of the Captivity an

outline of sacred ordinances for the future restoration.

From these and similar facts it follows indisputably, that

the true and spiritual religion which the prophets and like-

minded priests maintained at once against heathenism and

against unspiritual worship of Jehovah as a mere national

deity without moral attributes, was not a finished but a

growing system, not finally embodied in authoritative

documents, but propagated mainly by direct personal efforts.

A.t the same time these personal efforts were accompanied

and supported by the gradual rise of a sacred literature.

Though the priestly ordinances were mainly published by

oral decisions of the priests, which are, in fact, wbat is

usually meant by the word law (Torah) in writings earlier

than the Captivity, there can be no reasonable doubt that

the priests possessed written legal collections of greater or

less extent from the time of Moses downwards. Again,

the example of Ezekiel, and the obvious fact that the law¬

book found at the time of Josiah contained provisions

which were not up to that time an acknowledged part of

the law of the land, makes it probable that legal provisions,

which the prophets and their priestly allies felt to be

necessary for the maintenance of the truth, were often

embodied in legislative programmes, by which previous

legal tradition was gradually modified. Then the prophetsj

especially when they failed to produce immediate reforma¬

tion, began from the 8th century, if not still earlier, to-

commit their oracles to writing; and these written pro¬

phecies—circulating widely in a nation which had attained

a high degree of literary culture, and frequently cited by

later seers—disseminated prophetic teaching in a permanent

form. Long before this time music and song had been prac¬

tised in the prophetic circle of Samuel, and were introduced

under David into the service of the sanctuary. Another

important vehicle of religious instruction was the written

history of the nation, which could not fail to be generally

set forth in the theocratic spirit in which all loftier

Hebrew patriotism had its root. And, indeed, the literary

diffusion of spiritual ideas was not confined to the direct

efforts of priests and prophets. In spite of the crass and

unspiritual character of the mass of the people, the noblest

traditions of national life were entwined with religious con¬

victions, and the way in which a prophet, like Amos, could

arise untrained from among the herdsmen of the wilderness

of Judah, shows how deep and pure a current of spiritual

faith flowed among the more thoughtful of the laity.

Prophecy itself may from one point of view be regarded

simply as the brightest efflorescence of the lay element in

the religion of Israel, the same element which in subjective

form underlies many of the Psalms, and in a shape less

highly developed tinged the whole proverbial and popular

literature of the nation; for in the Hebrew commonwealth

popular literature had not yet sunk to represent the lowest

impulses of national life.

Close of the Old Testament Development. Formation of

the Canon.—The struggle between spiritual and unspiritual The Exile

religion was brought to a crisis when the prophetic predic-an(i ®e‘

tions of judgment on national sin were fulfilled in the fairstora lon'

of the kingdom of Judah. The' merely political worship

of Jehovah as the tutelary god of the state was now reduced

to absurdity. Faith in the covenant God was impossible

except on the principles of spiritual belief. Nor did the

restoration by Cyrus affect this result. No political future

lay before the returning exiles, and continued confidence in

the destiny of the race was not separable from the religious

ideas and Messianic hopes of the prophets. To obey the

law of Jehovah and patiently to await the coming

Deliverer was the only distinctive vocation of the com¬

munity that gathered in the new Jerusalem; and after

a period of misfortune and failure, in which the whole

nation seemed ready to collapse in despair, this voca¬

tion was dearly recognized and embodied in permanent

institutions in the reformation of'Ezra and Nehemiah (445 Roforma-

B.c.) But with this victory the spiritual religion passed tion and

into a stationary state. The spirit of prophecy, long^',^”k

decadent, expired with Malachi, the younger contemporary0 zra‘

of Nehemiah ; and the whole concern of the nation from

this time downwards was simply to preserve the sacred -

inheritance of the past. The Exile had so utterly broken

all continuity of national life, that that inheritance could

only be sought in the surviving monuments of sacred

literature. To these, more than to the expiring voice of

prophecy in their midst, the founders of the new theocracy

turned for guidance. The books that had upheld the

exiles’ faith, when all outward ordinances of religion were

lacking, were also the fittest teachers of the restored com¬

munity. Previous reformers had been statesmen or pro¬

phets. Ezra is a scribe who comes to Jerusalem armed,

not with a fresh message from the Lord, but with “the '

book of the law of Moses.” This law-book was the Penta¬

teuch, and the public recognition of it as the rule of the

theocracy was the declaration that the religious ordinances

of Israel had ceased to admit of development, and the first

step towards the substitution of a canon or authoritative

collection of Scriptures for the living guidance of the

prophetic voice. A second step in the same direction is

ascribed to Nehemiah by a tradition intrinsically probable,

though of no great external authority. He, it is said,

collected a library which, besides documents of temporary

importance, embraced “the books about the kings and

prophets, and the writings of David" (2 Mac. ii. 13.)

Certainly a complete body of the remains of the prophets,

with an authentic account of the history of the period of

their activity, must soon have been felt to be scarcely

second in importance to the law; and so Nehemiah may

very well be supposed to have begun the collection which

now forms the second part of the Hebrew Bible, embracing,

under the general title of The Prophets, the historical books Second

of Joshua, Judges, Samuel, Kings (Earlier Prophets), and canon,

the four prophetic books of Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and

the twelve minor prophets (Latter Prophets). The mention

of the writings of David implies that Nehemiah also began

the formation of the third and last part of the Hebrew

canon, which comprises, under the title of Ketubim (Scrip- Third

tures, Hagiographa), the Psalms, Proverbs, Job, the five cari(m-

Megillot or rolls (Canticles, Ruth, Lamentations, Eccle¬

siastes, Esther), and, finally, Daniel, Ezra, Nehemiah, and

Chronicles. It is certain, however, that this part of the

collection was not completed till long after Nehemiah’s

time; for to say nothing of the disputed dates of Ecclesiastes

and Daniel, the book of Chronicles contains genealogies

which go down at least to the close of the Persian period.

The miscellaneous character of the Ketubim seems, in

fact, to show that after the Law and the Prophets were

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Athens-BOI > (647) Page 635 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193658712 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|