Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Athens-BOI

(196) Page 184

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

184

Mugheir), the earliest capital of the country ; and Babylon,

with its suburb, Borsippa (Sirs Nirnrud), as well as the

two Sipparas (the Sepharvaim of Scripture, now Mosaib),

occupied both the Arabian and Chaldean side of the river.

(See Babylon.) The Araxes, or “ Biver of Babylon,” was

conducted through a deep valley into the heart of Arabia,

irrigating the land through which it passed; and to the

south of it lay the great inland fresh-water sea of Nedjef,

surrounded by red sandstone cliffs of considerable height,

40 miles in length and 35 in breadth in the widest part.

Above and below this sea, from Borsippa to Kufa, extend

the famous Chaldean marshes, where Alexander was nearly

lost (Arrian, Exp. Al., vii. 22.; Strab., xvi. 1, § 12,) ; but

these depend upon the state of the Hindiyah canal, dis¬

appearing altogether when it is closed. Between the sea

of Nedjef and Ur, but on the left side of the Euphrates,

was Erech (now Warha), which with Nipur or Calneh (now

Niffer), Surippac (Senkereh?), and Babylon (now Hillah),

formed the tetrapolis of Sumir or Shinar. This north¬

western part of Chaldea was also called Gan-duniyas or

Gun-duni after the accession of the Cassite dynasty. South¬

eastern Chaldea, on the other hand, was termed Accad,

though the name came also to be applied to the whole of

Babylonia. The Caldai, or Chaldeans, are first met with

in the 9th century p.c. as a small tribe on the Persian Gulf,

whence they slowly moved northwards, until under

Merodach-Baladan they made themselves masters of

Babylon, and henceforth formed so important an element

in the population of the country, as in later days to give

their name to the whole of it. In the inscriptions, how¬

ever, Chaldea represents the marshes of the sea-coast, and

Teredon was one of their ports. The whole territory was

thickly studded with towns; but among all this “ vast

number of great cities,” to use the words of Herodotus,

Cuthah, or Tiggaba (now Ibrahim), Chilmad (Kalwadah),

Is {Hit), and Dur-aba {Akkerlcuf) alone need be mentioned,

The cultivation of the country was regulated by canals,

the three chief of which carried off the waters of the

Euphrates towards the Tigris above Babylon,—the “ Royal

River,” or Ar-Malcha, entering the Tigris a little below

Baghdad, the Nahr-Malcha running across to the site of

Seleucia, and the Nahr-Kutha passing through Ibrahim.

The Pallacopas, on the other side of the Euphrates, supplied

an immense lake in the neighbourhood of Borsippa. So

great was the fertility of the soil that, according to

Herodotus (i. 193), grain commonly returned two hundred¬

fold to the sower, and occasionally three hundredfold.

Pliny, too (//. N., xviii. 17), says that wheat was cut twice,

and afterwards was good keep for sheep; and Berosus

remarked that wheat, barley, sesame, ochrys, palms, apples,

and many kinds of shelled fruit grew wild, as wheat still

does in the neighbourhood of Anah. A Persian poem

celebrated the 360 uses of the palm (Strab., xvi. 1, 14), and

Ammianus Marcellinus (xxiv. 3) states that from the point

reached by Julian’s army to the shores of the Persian Gulf

was one continuous forest of verdure.

Such a country was well fitted to be one of the primeval

seats of civilisation. Where brick lay ready to hand, and

climate and soil needed only settled life and moderate labour

to produce all that man required, it was natural that the

great civilising power of Western Asia should take its rise.

The history of the origin and development of this civilisa¬

tion, interesting and important as it is, has but recently been

made known to us by the decipherment of the native monu¬

ments. The scanty notices and conflicting statements of

classical writers have been replaced by the evidence of con¬

temporaneous documents; and though the materials are still

but a tithe of what we may hope hereafter to obtain, we can

sketch the outlines of the history, the art, and the science of

the powerful nations of the Tigris and Euphrates. Before

[GEOGKArilY.

doing so, however, it would be well to say a few words

in regard to our classical sources of information, the

only ones hitherto available. The principal of these is

Berosus, the Manetho of Babylonia, who flourished at the

time of Alexander’s conquests (though see Havet, Memoire

sur la Date des Ecrits qui portent les noms de Berose et dc

Manethon). He was priest of Bel, and translated the

records and astronomy of his nation into Greek. His

works have unfortunately perished, but the second and

third hand quotations from them, which we have in Euse¬

bius and other writers, have been strikingly verified by

inscriptions so far as regards their main facts. The story

of the flood taken from Berosus, for instance, is almost

identical with the one preserved on the cuneiform tablets.

Numerical figures, however, as might be expected, are

untrustworthy. According to Berosus, ten kings reigned

before the Deluge for 120 saroi, or 432,000 years, begin¬

ning with Alorus of Babylon and ending with Otiartes

(Opartes) of Larankha, and his son Sisuthrus, the hero

of the flood. Then came eight dynasties, which are given

as follows : —

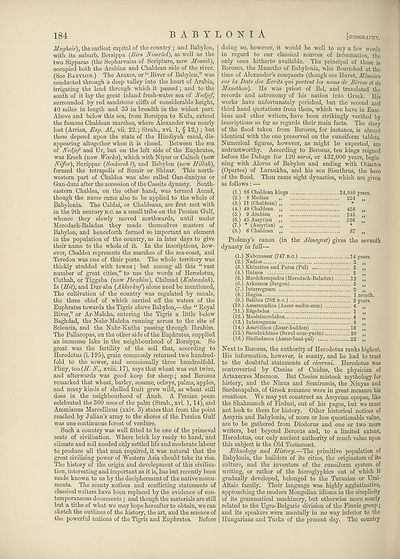

(1.) 86 Chaldean kings 84,080 years.

(2.) 8 Median ,, 224

(3.) 11 (Chaldean) ,, *

(4.) 49 Chaldean ,, 458 ,,

(5.) 9 Arabian 245 ,,

(6.) 45 Assyrian ,, 526 ,,

(7.) * (Assyrian) *

(8.) 6 Chaldean ,, 87 ,,

Ptolemy’s canon (in the Almagest) gives the seventh

dynasty in full—

(1.) Nabonassar (747 b.c.) 14 years.

(2.) Radios 2 ,,

(3.) Khinziros and Poros (Pul) 5 ,,

(4.) Ilulseos (. 5 ,,

(5.) Mardokempados (Merodach-Baladan) 12 ,,

(6.) Arkeanos (Sargon). 5 ,,

(7.) Interregnum 2 ,,

8. ) Hagisa 1 month.

9. ) Belibos (702 b.c.) 3 years.

(10.) Assaranadios (Assur-nadin-sum) 6 ,,

(11.) Regebelos 1 ,,

(l2.) Mesesimordakos 4 ,,

(13.) Interregnum 8 ,,

(14.) Asaridinos (Essar-haddon) 13 ,,

(15.) Saosdukhinos (Savul-sum-yucin) 20 ,,

(16.) Sineladanos (Assur-bani-pal) 22 ,,

Next to Berosus, the authority of Herodotus ranks highest.

His information, however, is scanty, and he had to trust

to the doubtful statements of ciceroni. Herodotus was

controverted by Ctesias of Cnidus, the physician of

Artaxerxes Mnemon. But Ctesias mistook mythology for

history, and the Ninus and Semiramis, the Ninyas and

Sardanapalus, of Greek romance were in great measure his

creations. We may yet construct an Assyrian epopee, like

the Shahnameh of Eirdusi, out of his pages, but we must

not look to them for history. Other historical notices of

Assyria and Babylonia, of more or less questionable value,

are to be gathered from Diodorus and one or two more

writers, but beyond Berosus and, to a limited extent,

Herodotus, our only ancient authority of much value upon

this subject is the Old Testament.

Ethnology and History.—The primitive population of

Babylonia, the builders of its cities, the originators of its

culture, and the inventors of the cuneiform system of

writing, or rather of the hieroglyphics out of which it

gradually developed, belonged to the Turanian or Ural-

Altaic family. Their language was highly agglutinative,

approaching the modern Mongolian idioms in the simplicity

of its grammatical machinery, but otherwise more nearly

related to the Ugro-Bulgaric division of the Finnic group;

and its speakers were mentally in no way inferior to the

Hungarians and Turks of the present day. The country

BABYLONIA

Mugheir), the earliest capital of the country ; and Babylon,

with its suburb, Borsippa (Sirs Nirnrud), as well as the

two Sipparas (the Sepharvaim of Scripture, now Mosaib),

occupied both the Arabian and Chaldean side of the river.

(See Babylon.) The Araxes, or “ Biver of Babylon,” was

conducted through a deep valley into the heart of Arabia,

irrigating the land through which it passed; and to the

south of it lay the great inland fresh-water sea of Nedjef,

surrounded by red sandstone cliffs of considerable height,

40 miles in length and 35 in breadth in the widest part.

Above and below this sea, from Borsippa to Kufa, extend

the famous Chaldean marshes, where Alexander was nearly

lost (Arrian, Exp. Al., vii. 22.; Strab., xvi. 1, § 12,) ; but

these depend upon the state of the Hindiyah canal, dis¬

appearing altogether when it is closed. Between the sea

of Nedjef and Ur, but on the left side of the Euphrates,

was Erech (now Warha), which with Nipur or Calneh (now

Niffer), Surippac (Senkereh?), and Babylon (now Hillah),

formed the tetrapolis of Sumir or Shinar. This north¬

western part of Chaldea was also called Gan-duniyas or

Gun-duni after the accession of the Cassite dynasty. South¬

eastern Chaldea, on the other hand, was termed Accad,

though the name came also to be applied to the whole of

Babylonia. The Caldai, or Chaldeans, are first met with

in the 9th century p.c. as a small tribe on the Persian Gulf,

whence they slowly moved northwards, until under

Merodach-Baladan they made themselves masters of

Babylon, and henceforth formed so important an element

in the population of the country, as in later days to give

their name to the whole of it. In the inscriptions, how¬

ever, Chaldea represents the marshes of the sea-coast, and

Teredon was one of their ports. The whole territory was

thickly studded with towns; but among all this “ vast

number of great cities,” to use the words of Herodotus,

Cuthah, or Tiggaba (now Ibrahim), Chilmad (Kalwadah),

Is {Hit), and Dur-aba {Akkerlcuf) alone need be mentioned,

The cultivation of the country was regulated by canals,

the three chief of which carried off the waters of the

Euphrates towards the Tigris above Babylon,—the “ Royal

River,” or Ar-Malcha, entering the Tigris a little below

Baghdad, the Nahr-Malcha running across to the site of

Seleucia, and the Nahr-Kutha passing through Ibrahim.

The Pallacopas, on the other side of the Euphrates, supplied

an immense lake in the neighbourhood of Borsippa. So

great was the fertility of the soil that, according to

Herodotus (i. 193), grain commonly returned two hundred¬

fold to the sower, and occasionally three hundredfold.

Pliny, too (//. N., xviii. 17), says that wheat was cut twice,

and afterwards was good keep for sheep; and Berosus

remarked that wheat, barley, sesame, ochrys, palms, apples,

and many kinds of shelled fruit grew wild, as wheat still

does in the neighbourhood of Anah. A Persian poem

celebrated the 360 uses of the palm (Strab., xvi. 1, 14), and

Ammianus Marcellinus (xxiv. 3) states that from the point

reached by Julian’s army to the shores of the Persian Gulf

was one continuous forest of verdure.

Such a country was well fitted to be one of the primeval

seats of civilisation. Where brick lay ready to hand, and

climate and soil needed only settled life and moderate labour

to produce all that man required, it was natural that the

great civilising power of Western Asia should take its rise.

The history of the origin and development of this civilisa¬

tion, interesting and important as it is, has but recently been

made known to us by the decipherment of the native monu¬

ments. The scanty notices and conflicting statements of

classical writers have been replaced by the evidence of con¬

temporaneous documents; and though the materials are still

but a tithe of what we may hope hereafter to obtain, we can

sketch the outlines of the history, the art, and the science of

the powerful nations of the Tigris and Euphrates. Before

[GEOGKArilY.

doing so, however, it would be well to say a few words

in regard to our classical sources of information, the

only ones hitherto available. The principal of these is

Berosus, the Manetho of Babylonia, who flourished at the

time of Alexander’s conquests (though see Havet, Memoire

sur la Date des Ecrits qui portent les noms de Berose et dc

Manethon). He was priest of Bel, and translated the

records and astronomy of his nation into Greek. His

works have unfortunately perished, but the second and

third hand quotations from them, which we have in Euse¬

bius and other writers, have been strikingly verified by

inscriptions so far as regards their main facts. The story

of the flood taken from Berosus, for instance, is almost

identical with the one preserved on the cuneiform tablets.

Numerical figures, however, as might be expected, are

untrustworthy. According to Berosus, ten kings reigned

before the Deluge for 120 saroi, or 432,000 years, begin¬

ning with Alorus of Babylon and ending with Otiartes

(Opartes) of Larankha, and his son Sisuthrus, the hero

of the flood. Then came eight dynasties, which are given

as follows : —

(1.) 86 Chaldean kings 84,080 years.

(2.) 8 Median ,, 224

(3.) 11 (Chaldean) ,, *

(4.) 49 Chaldean ,, 458 ,,

(5.) 9 Arabian 245 ,,

(6.) 45 Assyrian ,, 526 ,,

(7.) * (Assyrian) *

(8.) 6 Chaldean ,, 87 ,,

Ptolemy’s canon (in the Almagest) gives the seventh

dynasty in full—

(1.) Nabonassar (747 b.c.) 14 years.

(2.) Radios 2 ,,

(3.) Khinziros and Poros (Pul) 5 ,,

(4.) Ilulseos (. 5 ,,

(5.) Mardokempados (Merodach-Baladan) 12 ,,

(6.) Arkeanos (Sargon). 5 ,,

(7.) Interregnum 2 ,,

8. ) Hagisa 1 month.

9. ) Belibos (702 b.c.) 3 years.

(10.) Assaranadios (Assur-nadin-sum) 6 ,,

(11.) Regebelos 1 ,,

(l2.) Mesesimordakos 4 ,,

(13.) Interregnum 8 ,,

(14.) Asaridinos (Essar-haddon) 13 ,,

(15.) Saosdukhinos (Savul-sum-yucin) 20 ,,

(16.) Sineladanos (Assur-bani-pal) 22 ,,

Next to Berosus, the authority of Herodotus ranks highest.

His information, however, is scanty, and he had to trust

to the doubtful statements of ciceroni. Herodotus was

controverted by Ctesias of Cnidus, the physician of

Artaxerxes Mnemon. But Ctesias mistook mythology for

history, and the Ninus and Semiramis, the Ninyas and

Sardanapalus, of Greek romance were in great measure his

creations. We may yet construct an Assyrian epopee, like

the Shahnameh of Eirdusi, out of his pages, but we must

not look to them for history. Other historical notices of

Assyria and Babylonia, of more or less questionable value,

are to be gathered from Diodorus and one or two more

writers, but beyond Berosus and, to a limited extent,

Herodotus, our only ancient authority of much value upon

this subject is the Old Testament.

Ethnology and History.—The primitive population of

Babylonia, the builders of its cities, the originators of its

culture, and the inventors of the cuneiform system of

writing, or rather of the hieroglyphics out of which it

gradually developed, belonged to the Turanian or Ural-

Altaic family. Their language was highly agglutinative,

approaching the modern Mongolian idioms in the simplicity

of its grammatical machinery, but otherwise more nearly

related to the Ugro-Bulgaric division of the Finnic group;

and its speakers were mentally in no way inferior to the

Hungarians and Turks of the present day. The country

BABYLONIA

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Athens-BOI > (196) Page 184 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193652849 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|