Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Athens-BOI

(69) Page 57 - ATT

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

A T T-

But the new favourite found, as Bolingbroke had found

before him, that it was quite as hard to keep the shadow

of power under a vagrant and mendicant prince as to

keep the reality of power at Westminster. Though James

had neither territories nor revenues, neither army nor navy,

there was more faction and more intrigue among his

courtiers than among those of his successful rival. Atter-

bury soon perceived that his counsels were disregarded, if

not distrusted. His proud spirit was deeply wounded.

He quitted Paris, fixed his residence at Montpellier, gave

up politics, and devoted himself entirely to letters. In the

sixth year of his exile he had so severe an illness that his

daughter, herself in very delicate health, determined to run

all risks that she might see him once more. Having

obtained a licence from the English Government, she went

by sea to Bordeaux, but landed there in such a state that

she could travel only by boat or in a litter. Her father,

in spite of his infirmities, set out from Montpellier to meet

her; and she, with the impatience which is often the sign

of approaching death, hastened towards him. Those who

were about her in vain implored her to travel slowly.

She said that every hour was precious, that she only wished

to see her papa and to die. She met him at Toulouse,

embraced him, received from his hand the sacred bread

and wine, and thanked God that they had passed one day

in each other’s society before they parted for ever. She

died that night.

It was some time before even the strong mind of Atter-

bury recovered from this cruel blow. As soon as he was

himself again he became eager for action and conflict; for

grief, which disposes gentle natures to retirement, to inac¬

tion, and to meditation, only makes restless spirits more

restless. The Pretender, dull and bigoted as he was, had

found out that he had not acted wisely in parting with

one who, though a heretic, was, in abilities and accom¬

plishments, the foremost man of the Jacobite party. The

bishop was courted back, and was without much difficulty

induced to return to Paris, and to become once more the

phantom minister of a phantom monarchy. But his long

and troubled life was drawing to a close. To the last,

however, his intellect retained all its keenness and vigour.

He learned, in the ninth year of his banishment, that he

had been accused by Oldmixon, as dishonest and malignant

a scribbler as any that has been saved from oblivion by

the Dunciad, of having, in concert with other Christ

Churchmen, garbled Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion.

The charge, as respected Atterbury, had not the slightest

foundation; for he was not one of the editors of the

History, and never saw it till it was printed. He

published a short vindication of himself, which is a model

in its kind, luminous, temperate, and dignified. A copy

of this little work he sent to the Pretender, with a letter

singularly eloquent and graceful. It was impossible, the

old man said, that he should write anything on such a

subject without being reminded of the resemblance between

his own fate and that of Clarendon. They were the only

two English subjects that had ever been banished from

their country and debarred from all communication with

their friends by Act of Parliament. But here the resem¬

blance ended. One of the exiles had been so happy to

bear a chief part in the restoration of the royal house. All

that the other could now do was to die asserting the rights

of that house to the last. A few weeks after this letter

was written Atterbury died. He had just completed his

seventieth year.

His body was brought to England, and laid, with great

privacy, under the nave of Westminster Abbey. Only

three mourners followed the coffin. No inscription marks

the grave. That the epitaph with which Pope honoured

the memory of his friend does not appear on the walls of

-ATT 57

the great national cemetery is no subject of regret, for

nothing worse was ever written by Colley Cibber.

Those who wish for more complete information ahout Atterbury

may easily collect it from his sermons and his controversial writings,

from the report of the parliamentary proceedings against him,

which will be found in the State Trials ; from the five volumes of

his correspondence, edited by Mr Nichols, and from the first volume

of the Stuart papers, edited by Mr Glover. A very indulgent but

a very interesting account of the bishop’s political career will be

found in Lord Stanhope’s valuable History of England. (M.)

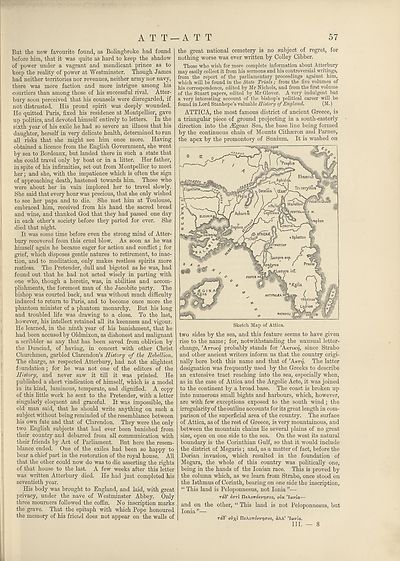

ATTICA, the most famous district of ancient Greece, is

a triangular piece of ground projecting in a south-easterly

direction into the Aegean Sea, the base line being formed

by the continuous chain of Mounts Cithseron and Parnes,

the apex by the promontory of Sunium. It is washed on

two sides by the sea, and this feature seems to have given

rise to the name; for, notwithstanding the unusual letter-

change, ’ArTLKrj probably stands for ’Aktikt/, since Strabo

and other ancient writers inform us that the country origi¬

nally bore both this name and that of ’Aktyj. The latter

designation was frequently used by the Greeks to describe

an extensive tract reaching into the sea, especially when,

as in the case of Attica and the Argolic Acte, it was joined

to the continent by a broad base. The coast is broken up

into numerous small bights and harbours, which, however,

are with few exceptions exposed to the south wind; the

irregularity of the outline accounts for its great length in com¬

parison of the superficial area of the country. The surface

of Attica, as of the rest of Greece, is very mountainous, and

between the mountain chains lie several plains of no great

size, open on one side to the sea. On the west its natural

boundary is the Corinthian Gulf, so that it would include

the district of Megaris; and, as a matter of fact, before the

Dorian invasion, which resulted in the foundation of

Megara, the whole of this country was politically one,

being in the hands of the Ionian race. This is proved by

the column which, as we learn from Strabo, once stood on

the Isthmus of Corinth, bearing on one side the inscription,

“ This land is Peloponnesus, not Ionia ”—

raS’ earl ne\oir6vvT](ros, ovk ’lairia—

and on the other, “ This land is not Peloponnesus, but

Ionia ”—

t«5’ oypid neXonSri/yaos, a\\' Tawfiz.

III. —

8

But the new favourite found, as Bolingbroke had found

before him, that it was quite as hard to keep the shadow

of power under a vagrant and mendicant prince as to

keep the reality of power at Westminster. Though James

had neither territories nor revenues, neither army nor navy,

there was more faction and more intrigue among his

courtiers than among those of his successful rival. Atter-

bury soon perceived that his counsels were disregarded, if

not distrusted. His proud spirit was deeply wounded.

He quitted Paris, fixed his residence at Montpellier, gave

up politics, and devoted himself entirely to letters. In the

sixth year of his exile he had so severe an illness that his

daughter, herself in very delicate health, determined to run

all risks that she might see him once more. Having

obtained a licence from the English Government, she went

by sea to Bordeaux, but landed there in such a state that

she could travel only by boat or in a litter. Her father,

in spite of his infirmities, set out from Montpellier to meet

her; and she, with the impatience which is often the sign

of approaching death, hastened towards him. Those who

were about her in vain implored her to travel slowly.

She said that every hour was precious, that she only wished

to see her papa and to die. She met him at Toulouse,

embraced him, received from his hand the sacred bread

and wine, and thanked God that they had passed one day

in each other’s society before they parted for ever. She

died that night.

It was some time before even the strong mind of Atter-

bury recovered from this cruel blow. As soon as he was

himself again he became eager for action and conflict; for

grief, which disposes gentle natures to retirement, to inac¬

tion, and to meditation, only makes restless spirits more

restless. The Pretender, dull and bigoted as he was, had

found out that he had not acted wisely in parting with

one who, though a heretic, was, in abilities and accom¬

plishments, the foremost man of the Jacobite party. The

bishop was courted back, and was without much difficulty

induced to return to Paris, and to become once more the

phantom minister of a phantom monarchy. But his long

and troubled life was drawing to a close. To the last,

however, his intellect retained all its keenness and vigour.

He learned, in the ninth year of his banishment, that he

had been accused by Oldmixon, as dishonest and malignant

a scribbler as any that has been saved from oblivion by

the Dunciad, of having, in concert with other Christ

Churchmen, garbled Clarendon’s History of the Rebellion.

The charge, as respected Atterbury, had not the slightest

foundation; for he was not one of the editors of the

History, and never saw it till it was printed. He

published a short vindication of himself, which is a model

in its kind, luminous, temperate, and dignified. A copy

of this little work he sent to the Pretender, with a letter

singularly eloquent and graceful. It was impossible, the

old man said, that he should write anything on such a

subject without being reminded of the resemblance between

his own fate and that of Clarendon. They were the only

two English subjects that had ever been banished from

their country and debarred from all communication with

their friends by Act of Parliament. But here the resem¬

blance ended. One of the exiles had been so happy to

bear a chief part in the restoration of the royal house. All

that the other could now do was to die asserting the rights

of that house to the last. A few weeks after this letter

was written Atterbury died. He had just completed his

seventieth year.

His body was brought to England, and laid, with great

privacy, under the nave of Westminster Abbey. Only

three mourners followed the coffin. No inscription marks

the grave. That the epitaph with which Pope honoured

the memory of his friend does not appear on the walls of

-ATT 57

the great national cemetery is no subject of regret, for

nothing worse was ever written by Colley Cibber.

Those who wish for more complete information ahout Atterbury

may easily collect it from his sermons and his controversial writings,

from the report of the parliamentary proceedings against him,

which will be found in the State Trials ; from the five volumes of

his correspondence, edited by Mr Nichols, and from the first volume

of the Stuart papers, edited by Mr Glover. A very indulgent but

a very interesting account of the bishop’s political career will be

found in Lord Stanhope’s valuable History of England. (M.)

ATTICA, the most famous district of ancient Greece, is

a triangular piece of ground projecting in a south-easterly

direction into the Aegean Sea, the base line being formed

by the continuous chain of Mounts Cithseron and Parnes,

the apex by the promontory of Sunium. It is washed on

two sides by the sea, and this feature seems to have given

rise to the name; for, notwithstanding the unusual letter-

change, ’ArTLKrj probably stands for ’Aktikt/, since Strabo

and other ancient writers inform us that the country origi¬

nally bore both this name and that of ’Aktyj. The latter

designation was frequently used by the Greeks to describe

an extensive tract reaching into the sea, especially when,

as in the case of Attica and the Argolic Acte, it was joined

to the continent by a broad base. The coast is broken up

into numerous small bights and harbours, which, however,

are with few exceptions exposed to the south wind; the

irregularity of the outline accounts for its great length in com¬

parison of the superficial area of the country. The surface

of Attica, as of the rest of Greece, is very mountainous, and

between the mountain chains lie several plains of no great

size, open on one side to the sea. On the west its natural

boundary is the Corinthian Gulf, so that it would include

the district of Megaris; and, as a matter of fact, before the

Dorian invasion, which resulted in the foundation of

Megara, the whole of this country was politically one,

being in the hands of the Ionian race. This is proved by

the column which, as we learn from Strabo, once stood on

the Isthmus of Corinth, bearing on one side the inscription,

“ This land is Peloponnesus, not Ionia ”—

raS’ earl ne\oir6vvT](ros, ovk ’lairia—

and on the other, “ This land is not Peloponnesus, but

Ionia ”—

t«5’ oypid neXonSri/yaos, a\\' Tawfiz.

III. —

8

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 3, Athens-BOI > (69) Page 57 - ATT |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193651198 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|