Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(850) Page 840

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

840

Systems

subse¬

quent to

Pitman’s.

SHORTHAND

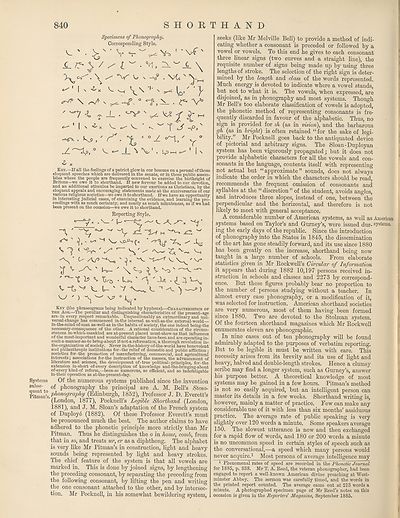

Specimens of Phonography.

Corresponding Style.

i- C- \ / i '

^ 1 I N ^ X v_<

-Vf '

^ . V], V \

V V -T? . Vti ' N|.m

^ \ ^ ° -I1, N. . r- ’V’

" ^ -i T -L ■ ^y"f ^ h-

^.. .Vs, ^ ' 0 / -^l.,' y°

.A ° V. «— 1 X ' . Lp i—i c—^ | \

^ x

Key.—If all the feelings of a patriot glow in our bosoms on a perusal of those

eloquent speeches which are delivered in the senate, or in those public assem¬

blies where the people are frequently convened to exercise the birthright of

Britons—we owe it to shorthand. If new fervour be added to our devotion,

and an additional stimulus be imparted to our exertions as Christians, by the

eloquent appeals and encouraging statements made at the anniversaries of our

various religious societies—we owe it to shorthand. If we have an opportunity

in interesting judicial cases, of examining the evidence, and learning the pro¬

ceedings with as much certainty, and nearly as much minuteness, as if we had

been present on the occasion—we owe it to shorthand.

Reporting Style.

' cjX . ^ V, vO^(* * ^ -X-

^ ^ V / ^ ^ ^

■ O ^ x V " v/°

' t 19 v . U, ' ^ '..u . I

V -fo ^ v, U N v X_ ^ ^ ^ —p)

W ' ) X w ^ ° Ar “

Key (the phraseograms being indicated by hyphens).—Characteeistics of

the Age.—The peculiar and distinguishing characteristics of the present-age

are-in every respect remarkable. Unquestionably an extraordinary and uni¬

versal-change has commenced in-the internal as-well-as-the external-world —

in-the-mind-of-man as-well-as in-the habits of society, the one indeed being-the

necessary-consequence of the other. A rational consideration of the circum¬

stances in-which-mankind are at-present placed must-show-us that influences

of the most-important and wonderful character have-been and are operating in-

such-a-manner-as-to bring-about if-not-a reformation, a thorough revolution in-

the-organization of society. Never in-the-history-of-the-world have benevolent

and philanthropic institutions for-the relief of domestic and public affliction ;

societies for-the promotion of manufacturing, commercial, and agricultural

interests; associations for-the instruction of the masses, the advancement of

literature and science, the development of-true political - principles, for-the

extension in-short of-every description of knowledge and-the-bringing-about

of-every kind-of reform,—been-so numerous, so efficient, and so indefatigable

in-their operation as at-the-present-day.

Of the numerous systems published since the invention

of phonography the principal are A. M. Bell’s Steno-

phonography (Edinburgh, 1852), Professor J. D. Everett’s

(London, 1877), Pocknell’s Legible Shorthand (London,

1881), and J. M. Sloan’s adaptation of the French system

of Duploye (1882). Of these Professor Everett’s must

be pronounced much the best. The author claims to have

adhered to the phonetic principle more strictly than Mr

Pitman. Thus he distinguishes the o in home, comb, from

that in so, and treats ur, er as a diphthong. The alphabet

is very like Mr Pitman’s in construction, light and heavy

sounds being represented by light and heavy strokes.

The chief feature of the system is that all vowels are

marked in. This is done by joined signs, by lengthening

the preceding consonant, by separating the preceding from

the following consonant, by lifting the pen and writing

the one consonant attached to the other, and by intersec¬

tion. Mr Pocknell, in his somewhat bewildering system,

seeks (like Mr Melville Bell) to provide a method of indi¬

cating whether a consonant is preceded or followed by a

vowel or vowels. To this end he gives to each consonant

three linear signs (two curves and a straight line), the

requisite number of signs being made up by using three

lengths of stroke. The selection of the right sign is deter¬

mined by the length and class of the words represented.

Much energy is devoted to indicate where a vowel stands,

but not to what it is. The vowels, when expressed, are

disjoined, as in phonography and most systems. Though

Mr Bell’s too elaborate classification of vowels is adopted,

the phonetic method of representing consonants is fre¬

quently discarded in favour of the alphabetic. Thus, no

sign is provided for zh (as in vision), and the barbarous

p'A (as in bright) is often retained “for the sake of legi¬

bility.” .Mr Pocknell goes back to the antiquated device

of pictorial and arbitrary signs. The Sloan-Duployan

system has been vigorously propagated; but it does not

provide alphabetic characters for all the vowels and con¬

sonants in the language, contents itself with representing

not actual but “approximate” sounds, does not always

indicate the order in which the characters should be read,

recommends the frequent omission of consonants and

syllables at the “ discretion ” of the student, avoids angles,

and introduces three slopes, instead of one, between the

perpendicular and the horizontal, and therefore is not

likely to meet with general acceptance.

A considerable number of American systems, as well as American

systems based on Taylor’s and Gurney’s, were issued dur- systems,

ing the early days of the republic. Since the introduction

of phonography into the States in 1845, the dissemination

of the art has gone steadily forward, and its use since 1880

has been greatly on the increase, shorthand being now

taught in a large number of schools. From elaborate

statistics given in Mr Kockwell’s Circular of Information

it appears that during 1882 10,197 persons received in¬

struction in schools and classes and 2273 by correspond¬

ence. But these figures probably bear no proportion to

the number of persons studying without a teacher. In

almost every case phonography, or a modification of it,

was selected for instruction. American shorthand societies

are very numerous, most of them having been formed

since 1880. Two are devoted to the Stolzean system.

Of the fourteen shorthand magazines which Mr Bockwell

enumerates eleven are phonographic.

In nine cases out of ten phonography will be found

admirably adapted to the purposes of verbatim reporting.

But to be legible it must be written with care. This

necessity arises from its brevity and its use of light and

heavy, halved and double-length strokes. Hence a clumsy

scribe may find a longer system, such as Gurney’s, answer

his purpose better. A theoretical knowledge of most

systems may be gained in a few hours. Pitman’s method

is not so easily acquired, but an intelligent person can

master its details in a few weeks. Shorthand writing is,

however, mainly a matter of practice. Few can make any

considerable use of it with less than six months’ assiduous

practice. The average rate of public speaking is very

slightly over 120 words a minute. Some speakers average

150. The slowest utterance is now and then exchanged

for a rapid flow of words, and 180 or 200 words a minute

is no uncommon speed in certain styles of speech such as

the conversational,—a speed which many persons would

never acquire.1 Most persons of average intelligence may

1 Phenomenal rates of speed are recorded in the Phonetic Journal

for 1885, p. 338. Mr T. A. Reed, the veteran phonographer, had been

engaged to report a well-known American divine preaching at West¬

minster Abbey. The sermon was carefully timed, and the words in

the printed report counted. The average came out at 213 words a

minute. A photographed specimen page of Mr Reed’s notes on this

occasion is given in the Reporters’ Magazine, September 1885.

Systems

subse¬

quent to

Pitman’s.

SHORTHAND

Specimens of Phonography.

Corresponding Style.

i- C- \ / i '

^ 1 I N ^ X v_<

-Vf '

^ . V], V \

V V -T? . Vti ' N|.m

^ \ ^ ° -I1, N. . r- ’V’

" ^ -i T -L ■ ^y"f ^ h-

^.. .Vs, ^ ' 0 / -^l.,' y°

.A ° V. «— 1 X ' . Lp i—i c—^ | \

^ x

Key.—If all the feelings of a patriot glow in our bosoms on a perusal of those

eloquent speeches which are delivered in the senate, or in those public assem¬

blies where the people are frequently convened to exercise the birthright of

Britons—we owe it to shorthand. If new fervour be added to our devotion,

and an additional stimulus be imparted to our exertions as Christians, by the

eloquent appeals and encouraging statements made at the anniversaries of our

various religious societies—we owe it to shorthand. If we have an opportunity

in interesting judicial cases, of examining the evidence, and learning the pro¬

ceedings with as much certainty, and nearly as much minuteness, as if we had

been present on the occasion—we owe it to shorthand.

Reporting Style.

' cjX . ^ V, vO^(* * ^ -X-

^ ^ V / ^ ^ ^

■ O ^ x V " v/°

' t 19 v . U, ' ^ '..u . I

V -fo ^ v, U N v X_ ^ ^ ^ —p)

W ' ) X w ^ ° Ar “

Key (the phraseograms being indicated by hyphens).—Characteeistics of

the Age.—The peculiar and distinguishing characteristics of the present-age

are-in every respect remarkable. Unquestionably an extraordinary and uni¬

versal-change has commenced in-the internal as-well-as-the external-world —

in-the-mind-of-man as-well-as in-the habits of society, the one indeed being-the

necessary-consequence of the other. A rational consideration of the circum¬

stances in-which-mankind are at-present placed must-show-us that influences

of the most-important and wonderful character have-been and are operating in-

such-a-manner-as-to bring-about if-not-a reformation, a thorough revolution in-

the-organization of society. Never in-the-history-of-the-world have benevolent

and philanthropic institutions for-the relief of domestic and public affliction ;

societies for-the promotion of manufacturing, commercial, and agricultural

interests; associations for-the instruction of the masses, the advancement of

literature and science, the development of-true political - principles, for-the

extension in-short of-every description of knowledge and-the-bringing-about

of-every kind-of reform,—been-so numerous, so efficient, and so indefatigable

in-their operation as at-the-present-day.

Of the numerous systems published since the invention

of phonography the principal are A. M. Bell’s Steno-

phonography (Edinburgh, 1852), Professor J. D. Everett’s

(London, 1877), Pocknell’s Legible Shorthand (London,

1881), and J. M. Sloan’s adaptation of the French system

of Duploye (1882). Of these Professor Everett’s must

be pronounced much the best. The author claims to have

adhered to the phonetic principle more strictly than Mr

Pitman. Thus he distinguishes the o in home, comb, from

that in so, and treats ur, er as a diphthong. The alphabet

is very like Mr Pitman’s in construction, light and heavy

sounds being represented by light and heavy strokes.

The chief feature of the system is that all vowels are

marked in. This is done by joined signs, by lengthening

the preceding consonant, by separating the preceding from

the following consonant, by lifting the pen and writing

the one consonant attached to the other, and by intersec¬

tion. Mr Pocknell, in his somewhat bewildering system,

seeks (like Mr Melville Bell) to provide a method of indi¬

cating whether a consonant is preceded or followed by a

vowel or vowels. To this end he gives to each consonant

three linear signs (two curves and a straight line), the

requisite number of signs being made up by using three

lengths of stroke. The selection of the right sign is deter¬

mined by the length and class of the words represented.

Much energy is devoted to indicate where a vowel stands,

but not to what it is. The vowels, when expressed, are

disjoined, as in phonography and most systems. Though

Mr Bell’s too elaborate classification of vowels is adopted,

the phonetic method of representing consonants is fre¬

quently discarded in favour of the alphabetic. Thus, no

sign is provided for zh (as in vision), and the barbarous

p'A (as in bright) is often retained “for the sake of legi¬

bility.” .Mr Pocknell goes back to the antiquated device

of pictorial and arbitrary signs. The Sloan-Duployan

system has been vigorously propagated; but it does not

provide alphabetic characters for all the vowels and con¬

sonants in the language, contents itself with representing

not actual but “approximate” sounds, does not always

indicate the order in which the characters should be read,

recommends the frequent omission of consonants and

syllables at the “ discretion ” of the student, avoids angles,

and introduces three slopes, instead of one, between the

perpendicular and the horizontal, and therefore is not

likely to meet with general acceptance.

A considerable number of American systems, as well as American

systems based on Taylor’s and Gurney’s, were issued dur- systems,

ing the early days of the republic. Since the introduction

of phonography into the States in 1845, the dissemination

of the art has gone steadily forward, and its use since 1880

has been greatly on the increase, shorthand being now

taught in a large number of schools. From elaborate

statistics given in Mr Kockwell’s Circular of Information

it appears that during 1882 10,197 persons received in¬

struction in schools and classes and 2273 by correspond¬

ence. But these figures probably bear no proportion to

the number of persons studying without a teacher. In

almost every case phonography, or a modification of it,

was selected for instruction. American shorthand societies

are very numerous, most of them having been formed

since 1880. Two are devoted to the Stolzean system.

Of the fourteen shorthand magazines which Mr Bockwell

enumerates eleven are phonographic.

In nine cases out of ten phonography will be found

admirably adapted to the purposes of verbatim reporting.

But to be legible it must be written with care. This

necessity arises from its brevity and its use of light and

heavy, halved and double-length strokes. Hence a clumsy

scribe may find a longer system, such as Gurney’s, answer

his purpose better. A theoretical knowledge of most

systems may be gained in a few hours. Pitman’s method

is not so easily acquired, but an intelligent person can

master its details in a few weeks. Shorthand writing is,

however, mainly a matter of practice. Few can make any

considerable use of it with less than six months’ assiduous

practice. The average rate of public speaking is very

slightly over 120 words a minute. Some speakers average

150. The slowest utterance is now and then exchanged

for a rapid flow of words, and 180 or 200 words a minute

is no uncommon speed in certain styles of speech such as

the conversational,—a speed which many persons would

never acquire.1 Most persons of average intelligence may

1 Phenomenal rates of speed are recorded in the Phonetic Journal

for 1885, p. 338. Mr T. A. Reed, the veteran phonographer, had been

engaged to report a well-known American divine preaching at West¬

minster Abbey. The sermon was carefully timed, and the words in

the printed report counted. The average came out at 213 words a

minute. A photographed specimen page of Mr Reed’s notes on this

occasion is given in the Reporters’ Magazine, September 1885.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (850) Page 840 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193638329 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|