Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(836) Page 826 - SHI

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

826

S H I — S H I

The timbers generally are about 1 inch by | inch, and are sawn

out of a clean piece of American elm, then planed and rounded.

After being steamed they are fitted into the boat, and as soon as

each is in position, and before it cools, it is nailed fast with copper

nails. The gunwale is next fitted, a piece of American elm about 2

inches square ; a breast-hook is fitted forward, binding the gunwale,

top strake, stern, and apron together ; and aft the gunwale and top

strake are secured to the transom by either a wooden or iron knee.

A waring or stringer, about 3 inches by f inch, of American elm’

is then fitted on both sides of the boat, about 8 to 9 inches below

the gunwale, on the top of which the thwarts or seats rest. The

thwarts are secured by knees, which are fastened with clench bolts

through the gunwale and top strake and also through the thwart

and knee. The boat generally receives three coats of paint and is

then ready for service.

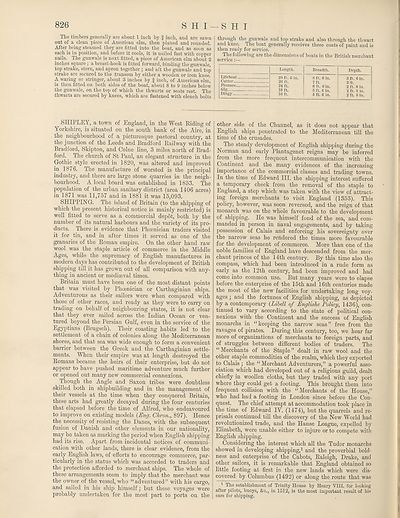

The following are the dimensions of boats in the British merchant

service:—

Lifeboat.

Cutter....

Pinnace..

Gig

Dingy....

Length.

28 ft. 6 in.

26 ft.

24 ft.

18 ft.

16 ft.

Breadth.

8 ft. 6 in.

7 ft.

6 ft. 6 in.

5 ft. 6 in.

5 ft. 6 in.

Depth.

3 ft. 6 in.

3 ft.

2 ft. 8 in.

2 ft. 3 in.

2 ft. 3 in.

SHIPLEY, a town of England, in the West Eiding of

Yorkshire, is situated on the south bank of the Aire, in

the neighbourhood of a picturesque pastoral country, at

the junction of the Leeds and Bradford Eailway with the

Bradford, Skipton, and Colne line, 3 miles north of Brad¬

ford. The church of St Paul, an elegant structure in the

Gothic style erected in 1820, was altered and improved

in 1876. The manufacture of worsted is the principal

industry, and there are large stone quarries in the neigh¬

bourhood. A local board was established in 1853. The

population of the urban sanitary district (area 1406 acres)

in 1871 was 11,757 and in 1881 it was 15,093.

SHIPPING. The island of Britain (to the shipping of

which the present historical notice is mainly restricted) is

well fitted to serve as a commercial depot, both by the

number of its natural harbours and the variety of its pro¬

ducts. There is evidence that Phoenician traders visited

it for tin, and in after times it served as one of the

granaries of the Eoman empire. On the other hand raw

wool was the staple article of commerce in the Middle

Ages, while the supremacy of English manufactures in

modern days has contributed to the development of British

shipping till it has grown out of all comparison with any¬

thing in ancient or mediaeval times.

Britain must have been one of the most distant points

that was visited by Phoenician or Carthaginian ships.

Adventurous as their sailors were when compared with

those of other races, and ready as they were to carry on

trading on behalf of neighbouring states, it is not clear

that they ever sailed across the Indian Ocean or ven¬

tured beyond the Persian Gulf, even in the service of the

Egyptians (Brugsch). Their coasting habits led to the

settlement of a chain of colonies along the Mediterranean

shores, and that sea was wide enough to form a convenient

barrier between the Greek and the Carthaginian settle¬

ments. When their empire was at length destroyed the

Eomans became the heirs of their enterprise, but do not

appear to have pushed maritime adventure much further

or opened out many new commercial connexions.

Though the Angle and Saxon tribes were doubtless

skilled both in shipbuilding and in the management of

their vessels at the time when they conquered Britain,

these arts had greatly decayed during the four centuries

that elapsed before the time of Alfred, who endeavoured

to improve on existing models (Eng. Chron., 897). Hence

the necessity of resisting the Danes, with the subsequent

fusion of Danish and other elements in our nationality,

may be taken as marking the period when English shipping

had its rise. Apart from incidental notices of communi¬

cation with other lands, there is clear evidence, from the

early English laws, of efforts to encourage commerce, par¬

ticularly in the status which was accorded to traders and

the protection afforded to merchant ships. The whole of

these arrangements seem to imply that the merchant was

the owner of the vessel, who “adventured” with his cargo,

and sailed in his ship himself; but these voyages were

probably undertaken for the most part to ports on the

other side of the Channel, as it does not ajjpear that

English ships penetrated to the Mediterranean till the

time of the crusades.

The steady development of English shipping during the

Norman and early Plantagenet reigns may be inferred

from the more frequent intercommunication with the

Continent and the many evidences of the increasing

importance of the commercial classes and trading towns.

In the time of Edward III. the shipping interest suffered

a temporary check from the removal of the staple to

England, a step which was taken with the view of attract¬

ing foreign merchants to visit England (1353). This

policy, however, was soon reversed, and the reign of that

monarch was on the whole favourable to the development

of shipping. He was himself fond of the sea, and com¬

manded in person in naval engagements, and by taking

possession of Calais and enforcing his sovereignty over

the narrow seas he rendered the times more favourable

for the development of commerce. More than one of the

noble families of England have descended from the mer¬

chant princes of the 14th century. By this time also the

compass, which had been introduced in a rude form as

early as the 12th century, had been improved and had

come into common use. But many years were to elapse

before the enterprise of the 15th and 16th centuries made

the most of the new facilities for undertaking long voy¬

ages ; and the fortunes of English shipping, as depicted

by a contemporary (Libell of Englishe Policy, 1436), con¬

tinued to vary according to the state of political con¬

nexions with the Continent and the success of English

monarchs in “ keeping the narrow seas ” free from the

ravages of pirates. During this century, too, we hear far

more of organizations of merchants to foreign parts, and

of struggles between different bodies of traders. The

“ Merchants of the Staple ” dealt in raw wool and the

other staple commodities of the realm, which they exported

to Calais ; the “Merchant Adventurers,” a powerful asso¬

ciation which had developed out of a religious guild, dealt

chiefly in woollen cloths, but they traded with any port

where they could get a footing. This brought them into

frequent collision with the “Merchants of the House,”

who had had a footing in London since before the Con¬

quest. The chief attempt at accommodation took place in

the time of Edward IY. (1474), but the quarrels and re¬

prisals continued till the discovery of the New World had

revolutionized trade, and the Hanse League, expelled by

Elizabeth, were unable either to injure or to compete with

English shipping.

Considering the interest which all the Tudor monarchs

showed in developing shipping,1 and the proverbial bold¬

ness and enterprise of the Cabots, Ealeigh, Drake, and

other sailors, it is remarkable that England obtained so

little footing at first in the new lands which were dis¬

covered by Columbus (1492) or along the route that was

1 The establishment of Trinity House by Henry VIII. for looking

after pilots, buoys, &c., in 1512, is the most important result of his

care for shipping.

S H I — S H I

The timbers generally are about 1 inch by | inch, and are sawn

out of a clean piece of American elm, then planed and rounded.

After being steamed they are fitted into the boat, and as soon as

each is in position, and before it cools, it is nailed fast with copper

nails. The gunwale is next fitted, a piece of American elm about 2

inches square ; a breast-hook is fitted forward, binding the gunwale,

top strake, stern, and apron together ; and aft the gunwale and top

strake are secured to the transom by either a wooden or iron knee.

A waring or stringer, about 3 inches by f inch, of American elm’

is then fitted on both sides of the boat, about 8 to 9 inches below

the gunwale, on the top of which the thwarts or seats rest. The

thwarts are secured by knees, which are fastened with clench bolts

through the gunwale and top strake and also through the thwart

and knee. The boat generally receives three coats of paint and is

then ready for service.

The following are the dimensions of boats in the British merchant

service:—

Lifeboat.

Cutter....

Pinnace..

Gig

Dingy....

Length.

28 ft. 6 in.

26 ft.

24 ft.

18 ft.

16 ft.

Breadth.

8 ft. 6 in.

7 ft.

6 ft. 6 in.

5 ft. 6 in.

5 ft. 6 in.

Depth.

3 ft. 6 in.

3 ft.

2 ft. 8 in.

2 ft. 3 in.

2 ft. 3 in.

SHIPLEY, a town of England, in the West Eiding of

Yorkshire, is situated on the south bank of the Aire, in

the neighbourhood of a picturesque pastoral country, at

the junction of the Leeds and Bradford Eailway with the

Bradford, Skipton, and Colne line, 3 miles north of Brad¬

ford. The church of St Paul, an elegant structure in the

Gothic style erected in 1820, was altered and improved

in 1876. The manufacture of worsted is the principal

industry, and there are large stone quarries in the neigh¬

bourhood. A local board was established in 1853. The

population of the urban sanitary district (area 1406 acres)

in 1871 was 11,757 and in 1881 it was 15,093.

SHIPPING. The island of Britain (to the shipping of

which the present historical notice is mainly restricted) is

well fitted to serve as a commercial depot, both by the

number of its natural harbours and the variety of its pro¬

ducts. There is evidence that Phoenician traders visited

it for tin, and in after times it served as one of the

granaries of the Eoman empire. On the other hand raw

wool was the staple article of commerce in the Middle

Ages, while the supremacy of English manufactures in

modern days has contributed to the development of British

shipping till it has grown out of all comparison with any¬

thing in ancient or mediaeval times.

Britain must have been one of the most distant points

that was visited by Phoenician or Carthaginian ships.

Adventurous as their sailors were when compared with

those of other races, and ready as they were to carry on

trading on behalf of neighbouring states, it is not clear

that they ever sailed across the Indian Ocean or ven¬

tured beyond the Persian Gulf, even in the service of the

Egyptians (Brugsch). Their coasting habits led to the

settlement of a chain of colonies along the Mediterranean

shores, and that sea was wide enough to form a convenient

barrier between the Greek and the Carthaginian settle¬

ments. When their empire was at length destroyed the

Eomans became the heirs of their enterprise, but do not

appear to have pushed maritime adventure much further

or opened out many new commercial connexions.

Though the Angle and Saxon tribes were doubtless

skilled both in shipbuilding and in the management of

their vessels at the time when they conquered Britain,

these arts had greatly decayed during the four centuries

that elapsed before the time of Alfred, who endeavoured

to improve on existing models (Eng. Chron., 897). Hence

the necessity of resisting the Danes, with the subsequent

fusion of Danish and other elements in our nationality,

may be taken as marking the period when English shipping

had its rise. Apart from incidental notices of communi¬

cation with other lands, there is clear evidence, from the

early English laws, of efforts to encourage commerce, par¬

ticularly in the status which was accorded to traders and

the protection afforded to merchant ships. The whole of

these arrangements seem to imply that the merchant was

the owner of the vessel, who “adventured” with his cargo,

and sailed in his ship himself; but these voyages were

probably undertaken for the most part to ports on the

other side of the Channel, as it does not ajjpear that

English ships penetrated to the Mediterranean till the

time of the crusades.

The steady development of English shipping during the

Norman and early Plantagenet reigns may be inferred

from the more frequent intercommunication with the

Continent and the many evidences of the increasing

importance of the commercial classes and trading towns.

In the time of Edward III. the shipping interest suffered

a temporary check from the removal of the staple to

England, a step which was taken with the view of attract¬

ing foreign merchants to visit England (1353). This

policy, however, was soon reversed, and the reign of that

monarch was on the whole favourable to the development

of shipping. He was himself fond of the sea, and com¬

manded in person in naval engagements, and by taking

possession of Calais and enforcing his sovereignty over

the narrow seas he rendered the times more favourable

for the development of commerce. More than one of the

noble families of England have descended from the mer¬

chant princes of the 14th century. By this time also the

compass, which had been introduced in a rude form as

early as the 12th century, had been improved and had

come into common use. But many years were to elapse

before the enterprise of the 15th and 16th centuries made

the most of the new facilities for undertaking long voy¬

ages ; and the fortunes of English shipping, as depicted

by a contemporary (Libell of Englishe Policy, 1436), con¬

tinued to vary according to the state of political con¬

nexions with the Continent and the success of English

monarchs in “ keeping the narrow seas ” free from the

ravages of pirates. During this century, too, we hear far

more of organizations of merchants to foreign parts, and

of struggles between different bodies of traders. The

“ Merchants of the Staple ” dealt in raw wool and the

other staple commodities of the realm, which they exported

to Calais ; the “Merchant Adventurers,” a powerful asso¬

ciation which had developed out of a religious guild, dealt

chiefly in woollen cloths, but they traded with any port

where they could get a footing. This brought them into

frequent collision with the “Merchants of the House,”

who had had a footing in London since before the Con¬

quest. The chief attempt at accommodation took place in

the time of Edward IY. (1474), but the quarrels and re¬

prisals continued till the discovery of the New World had

revolutionized trade, and the Hanse League, expelled by

Elizabeth, were unable either to injure or to compete with

English shipping.

Considering the interest which all the Tudor monarchs

showed in developing shipping,1 and the proverbial bold¬

ness and enterprise of the Cabots, Ealeigh, Drake, and

other sailors, it is remarkable that England obtained so

little footing at first in the new lands which were dis¬

covered by Columbus (1492) or along the route that was

1 The establishment of Trinity House by Henry VIII. for looking

after pilots, buoys, &c., in 1512, is the most important result of his

care for shipping.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (836) Page 826 - SHI |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193638147 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|