Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(830) Page 820

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

Fasten¬

ing.

Decks.

Caulk¬

ing.

820

SHIPBUILDING

Of the internal planking the lowest strake, or combination of

strakes, in the hold, is called the limber-strake. A limber is a

passage for water, of which there is one throughout the length of

the ship, on each side of the keelson, in order that any leakage

may find its way to the pumps.

The whole of the plank in the hold is called the ceiling. Those

strakes which come over the heads and heels of the timbers are

worked thicker than the general thickness of the ceiling, and are

distinguished as the thick strakes over the several heads. The

strakes under the ends of the beams of the different decks in a

man-of-war, and down to the ports of the deck below, if there were

any ports, were called the clamps of the particular decks to the

beams of which they are the support—as the gun-deck clamps, the

middle-deck clamps, &c. The strakes which work up to the sills

of the ports of the several decks were called the spirketting of

those decks—-as gun-deck spirketting, upper-deck spirketting, &c.

The. fastening of the plank is either “ single,” by which is meant

one fastening only in each strake as it passes each timber or

frame ; or it may be_ “double,” that is, with two fastenings into

each frame which it crosses ; or, again, the fastenings may be

“double and single,” meaning that the fastenings are double and

single alternately in the frames as they cross them. The fastenings

of planks consist generally either of nails or treenails, excepting

at the butts, which are secured by bolts. Several other bolts

ought to be driven in each shift of plank as additional security.

Bolts which are required to pass through the timbers as securities

to the shelf, waterway, knees, &c., should be taken advantage of

to supply the place of the regular fastening of the plank, not only

for the sake of economy, but also for the sake of avoiding unneces-

sarily wounding the timbers.

ihe decks of a wooden ship must not be considered merely as

platforms, but must be regarded as performing an important part

towards the general strength of the whole fabric. They are

generally laid in a longitudinal direction only, and are then use-

ful as a tie to resist extension, or as a strut to resist compression.

The outer strakes of decks at the sides of the ship are generally of

hard wood, and of greater thickness than the deck itself ; they are

called the waterway planks, and are sometimes dowelled to the

upper, surface of each beam. Their rigidity and strength is of

great impoitance, and great attention should be paid to them, and

caie taken that their scarphs are well secured by through-bolts,

and that there is a proper shift between their scarphs and the

scarphs of the shelf.

When the decks are considered as a tie, the importance of keep¬

ing as many strakes as possible entire for the whole length of the

ship must be evident; and a continuous strake of iron or steel

plates beneath the decks is of great value in this respect. The

straighter the deck, or the less the sheer or upward curvature at

the ends that may be given to it, the less liable will it be to any

alteration of length, and the stronger will it be. The ends of the

different planks forming one strake were made to butt on one beam,

and, as the fastenings are driven close to the ends, they did not

possess much strength to resist being torn out. The shifts of the

butts, therefore, of the different strakes required great attention

because the transference of the longitudinal strength of the deck

from one plank to another was thus made by means of the fasten-

mgs to the beams, the strakes not being united to each other

sideways. The introduction of iron decks or partial decks under

the wood has modified this.

These fastenings have, also to withstand the strain during the

process of caulking, which has a tendency to force the planks

sideways from the seam ; and, as the edges of planks of hard wood

will be less crushed or compressed than those of soft wood when

acted on by the caulking-iron, the strain to open the seam between

them to receive the caulking will be greater than with planks of

softer wood, and will require more secure fastenings to resist it

It may also be remarked that the quantity of fastenings should

inciease with the thickness of the plank which is to be secured

se^ oa^um caulking will have the greater mechani¬

cal effect the thicker the edge.

When the planks are fastened, the seams or the intervals

between the edges of the strakes are filled with oakum, and this is

beaten m or caulked with such care and force that the oakum

while undisturbed, is almost as hard as the plank itself. If the

openings of the seam were of equal widths throughout their depth

between the planks, it would be impossible to make the caulking

sufficiently compact to resist the water. At the bottom edges of

the seams the planks should be in contact throughout their length,

and ii om this contact they should gradually open upwards so

that, at the outer edge of a plank 10 inches thick, the space should

be about xt °f an inch, that is, about xV of an inch open for every

inch of thickness. It will hence be seen that, if the edges of the

planks are so prepared that when laid they fit closely for their

whole thickness, the force required to compress the outer edge by

driving the caulking-iron into the seams, to open them sufficiently

must be very great, and the fastenings of the planks must be such

as to be able to resist it. Bad caulking is very injurious in every

way, as leading to leakage and to the rotting of the planks them¬

selves at their edges.

Ships are generally built on blocks which are laid at a declivity Launch-

of about -g- inch to a foot. This is for the facility of launching ing.

them The inclined plane or sliding plank on which they are

launched has rather more inclination, or about | inch to the foot

for large ships, and a slight increase for smaller vessels. This

inclination will, however, in some measure, depend upon the depth

of water into which the ship is to be launched.

While a ship is in progress of being built her weight is partly

supported by her keel on the blocks and partly by shores In

order to launch her the weight must be taken off these supports

and transferred to a movable base ; and a platform must be erected

for the movable base to slide on. This platform must not only be

laid at the necessary inclination, but must be of sufficient height

to enable the ship to be water-borne and to preserve her from

striking the ground when she arrives at the end of the ways,

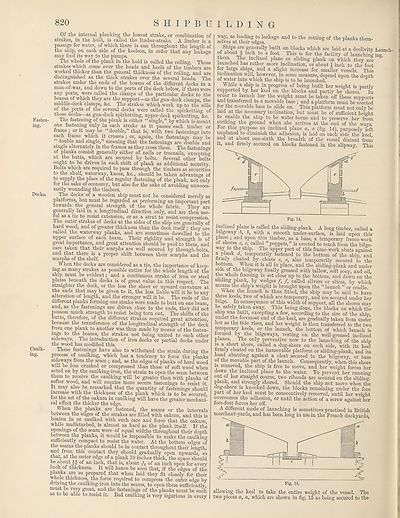

lor this purpose an inclined plane a, a (fig. 14), purposely left

unplaned to diminish the adhesion, is laid on each side the keel

and at about one-sixth the breadth of the vessel distant from

it, and firmly secured on blocks fastened in the slipway. This

Fig. 14.

inclined plane is called the sliding-plank. A long timber, called a

bilgeway o, b, with, a smooth under-surface, is laid upon this

plane ; and upon this timber, as a base, a temporary frame-work

of shores c, c, called “ poppets, ” is erected to reach from the bilge¬

way to the ship. The upper part of this frame-work abuts against

a plank d, temporarily fastened to the bottom of the ship, and

firmly cleated by cleats e, e, also temporarily secured to the

bottom When it is all in place, and the sliding-plank and under

side of the bilgeway finally greased with tallow, soft soap, and oil

the whole framing is set close up to the bottom, and down on the

sliding plank, by wedges /, /, called slivers or slices, by which

means the ship s weight is brought upon the “ launch ” or cradle

\\ hen the launch is thus fitted, the ship may be said to have

tliree keels, two of which are temporary, and are secured under her

bilge In consequence of this width of support, all the shores may

be safely taken away. This being done, the blocks on which the

ship was built, excepting a few, according to the size of the ship

under the foremost end of the keel, are gradually taken from under

her as the tide rises, and her weight is then transferred to the two

temporary keels, or the launch, the bottom of which launch is

formed by the bilgeways, resting on the well-greased inclined

planes. Ihe only preventive now to the launching of the ship

is a short shore, called a dog-shore on each side, with its heel

hrmly cleated on the immovable platform or sliding-plank, and its

head abutting against a cleat secured to the bilgeway, or base

of the movable part, of the launch. Consequently, when this shore

is removed, the ship is free to move, and her weight forces her

down the inclined plane to the water. To prevent her ruuniim

out of her straight course, two ribands are secured on the sliding^

plank, and. strongly shored. Should the ship not move when the

dog-shore is knocked down, the blocks remaining under the fore

part of her keel must be consecutively removed, until her weight

oveicomes the adhesion, or until the action of a screw against her

fore-foot forces her off.

A different mode of launching is sometimes practised in British

merchant-yards, and has been long in use in the French dockyards,

Fig. 15.

allowing the keel to take the entire weight of the vessel. The

two pieces a, a, which arc shown in fig. 15 as being secured to the

ing.

Decks.

Caulk¬

ing.

820

SHIPBUILDING

Of the internal planking the lowest strake, or combination of

strakes, in the hold, is called the limber-strake. A limber is a

passage for water, of which there is one throughout the length of

the ship, on each side of the keelson, in order that any leakage

may find its way to the pumps.

The whole of the plank in the hold is called the ceiling. Those

strakes which come over the heads and heels of the timbers are

worked thicker than the general thickness of the ceiling, and are

distinguished as the thick strakes over the several heads. The

strakes under the ends of the beams of the different decks in a

man-of-war, and down to the ports of the deck below, if there were

any ports, were called the clamps of the particular decks to the

beams of which they are the support—as the gun-deck clamps, the

middle-deck clamps, &c. The strakes which work up to the sills

of the ports of the several decks were called the spirketting of

those decks—-as gun-deck spirketting, upper-deck spirketting, &c.

The. fastening of the plank is either “ single,” by which is meant

one fastening only in each strake as it passes each timber or

frame ; or it may be_ “double,” that is, with two fastenings into

each frame which it crosses ; or, again, the fastenings may be

“double and single,” meaning that the fastenings are double and

single alternately in the frames as they cross them. The fastenings

of planks consist generally either of nails or treenails, excepting

at the butts, which are secured by bolts. Several other bolts

ought to be driven in each shift of plank as additional security.

Bolts which are required to pass through the timbers as securities

to the shelf, waterway, knees, &c., should be taken advantage of

to supply the place of the regular fastening of the plank, not only

for the sake of economy, but also for the sake of avoiding unneces-

sarily wounding the timbers.

ihe decks of a wooden ship must not be considered merely as

platforms, but must be regarded as performing an important part

towards the general strength of the whole fabric. They are

generally laid in a longitudinal direction only, and are then use-

ful as a tie to resist extension, or as a strut to resist compression.

The outer strakes of decks at the sides of the ship are generally of

hard wood, and of greater thickness than the deck itself ; they are

called the waterway planks, and are sometimes dowelled to the

upper, surface of each beam. Their rigidity and strength is of

great impoitance, and great attention should be paid to them, and

caie taken that their scarphs are well secured by through-bolts,

and that there is a proper shift between their scarphs and the

scarphs of the shelf.

When the decks are considered as a tie, the importance of keep¬

ing as many strakes as possible entire for the whole length of the

ship must be evident; and a continuous strake of iron or steel

plates beneath the decks is of great value in this respect. The

straighter the deck, or the less the sheer or upward curvature at

the ends that may be given to it, the less liable will it be to any

alteration of length, and the stronger will it be. The ends of the

different planks forming one strake were made to butt on one beam,

and, as the fastenings are driven close to the ends, they did not

possess much strength to resist being torn out. The shifts of the

butts, therefore, of the different strakes required great attention

because the transference of the longitudinal strength of the deck

from one plank to another was thus made by means of the fasten-

mgs to the beams, the strakes not being united to each other

sideways. The introduction of iron decks or partial decks under

the wood has modified this.

These fastenings have, also to withstand the strain during the

process of caulking, which has a tendency to force the planks

sideways from the seam ; and, as the edges of planks of hard wood

will be less crushed or compressed than those of soft wood when

acted on by the caulking-iron, the strain to open the seam between

them to receive the caulking will be greater than with planks of

softer wood, and will require more secure fastenings to resist it

It may also be remarked that the quantity of fastenings should

inciease with the thickness of the plank which is to be secured

se^ oa^um caulking will have the greater mechani¬

cal effect the thicker the edge.

When the planks are fastened, the seams or the intervals

between the edges of the strakes are filled with oakum, and this is

beaten m or caulked with such care and force that the oakum

while undisturbed, is almost as hard as the plank itself. If the

openings of the seam were of equal widths throughout their depth

between the planks, it would be impossible to make the caulking

sufficiently compact to resist the water. At the bottom edges of

the seams the planks should be in contact throughout their length,

and ii om this contact they should gradually open upwards so

that, at the outer edge of a plank 10 inches thick, the space should

be about xt °f an inch, that is, about xV of an inch open for every

inch of thickness. It will hence be seen that, if the edges of the

planks are so prepared that when laid they fit closely for their

whole thickness, the force required to compress the outer edge by

driving the caulking-iron into the seams, to open them sufficiently

must be very great, and the fastenings of the planks must be such

as to be able to resist it. Bad caulking is very injurious in every

way, as leading to leakage and to the rotting of the planks them¬

selves at their edges.

Ships are generally built on blocks which are laid at a declivity Launch-

of about -g- inch to a foot. This is for the facility of launching ing.

them The inclined plane or sliding plank on which they are

launched has rather more inclination, or about | inch to the foot

for large ships, and a slight increase for smaller vessels. This

inclination will, however, in some measure, depend upon the depth

of water into which the ship is to be launched.

While a ship is in progress of being built her weight is partly

supported by her keel on the blocks and partly by shores In

order to launch her the weight must be taken off these supports

and transferred to a movable base ; and a platform must be erected

for the movable base to slide on. This platform must not only be

laid at the necessary inclination, but must be of sufficient height

to enable the ship to be water-borne and to preserve her from

striking the ground when she arrives at the end of the ways,

lor this purpose an inclined plane a, a (fig. 14), purposely left

unplaned to diminish the adhesion, is laid on each side the keel

and at about one-sixth the breadth of the vessel distant from

it, and firmly secured on blocks fastened in the slipway. This

Fig. 14.

inclined plane is called the sliding-plank. A long timber, called a

bilgeway o, b, with, a smooth under-surface, is laid upon this

plane ; and upon this timber, as a base, a temporary frame-work

of shores c, c, called “ poppets, ” is erected to reach from the bilge¬

way to the ship. The upper part of this frame-work abuts against

a plank d, temporarily fastened to the bottom of the ship, and

firmly cleated by cleats e, e, also temporarily secured to the

bottom When it is all in place, and the sliding-plank and under

side of the bilgeway finally greased with tallow, soft soap, and oil

the whole framing is set close up to the bottom, and down on the

sliding plank, by wedges /, /, called slivers or slices, by which

means the ship s weight is brought upon the “ launch ” or cradle

\\ hen the launch is thus fitted, the ship may be said to have

tliree keels, two of which are temporary, and are secured under her

bilge In consequence of this width of support, all the shores may

be safely taken away. This being done, the blocks on which the

ship was built, excepting a few, according to the size of the ship

under the foremost end of the keel, are gradually taken from under

her as the tide rises, and her weight is then transferred to the two

temporary keels, or the launch, the bottom of which launch is

formed by the bilgeways, resting on the well-greased inclined

planes. Ihe only preventive now to the launching of the ship

is a short shore, called a dog-shore on each side, with its heel

hrmly cleated on the immovable platform or sliding-plank, and its

head abutting against a cleat secured to the bilgeway, or base

of the movable part, of the launch. Consequently, when this shore

is removed, the ship is free to move, and her weight forces her

down the inclined plane to the water. To prevent her ruuniim

out of her straight course, two ribands are secured on the sliding^

plank, and. strongly shored. Should the ship not move when the

dog-shore is knocked down, the blocks remaining under the fore

part of her keel must be consecutively removed, until her weight

oveicomes the adhesion, or until the action of a screw against her

fore-foot forces her off.

A different mode of launching is sometimes practised in British

merchant-yards, and has been long in use in the French dockyards,

Fig. 15.

allowing the keel to take the entire weight of the vessel. The

two pieces a, a, which arc shown in fig. 15 as being secured to the

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (830) Page 820 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193638069 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|