Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(788) Page 778

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

778

SHARK

same family as the spiked dog-fish, but grows to a much

larger size, specimens 15 feet long being frequently met

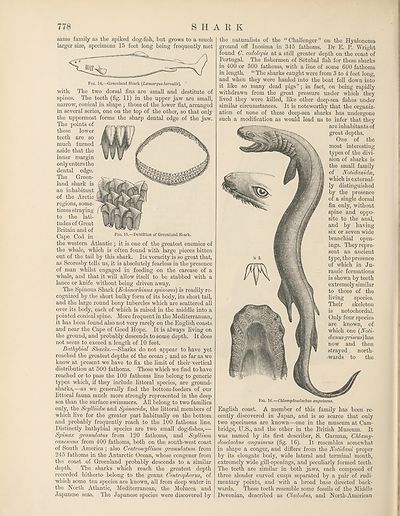

Fig. 15.—Dentition of Greenland Shark.

Fig. 14.—Greenland Shark {Lxmargus borealis).

with. The two dorsal fins are small and destitute of

spines. The teeth (fig. 11) in the upper jaw are small,

narrow, conical in shape ; those of the lower flat, arranged

in several series, one on the top of the other, so that only

the uppermost forms the sharp dental edge of the jaw.

The points of

these lower

teeth are so

much turned

aside that the

inner margin

only enters the

dental edge.

The Green¬

land shark is

an inhabitant

of the Arctic

regions, some¬

times straying

to the lati¬

tudes of Great

Britain and of

Cape Cod in

the western Atlantic ; it is one of the greatest enemies of

the whale, which is often found with large pieces bitten

out of the tail by this shark. Its voracity is so great that,

as Scoresby tells us, it is absolutely fearless in the presence

of man whilst engaged in feeding on the carcase of a

whale, and that it will allow itself to be stabbed with a

lance or knife without being driven away.

The Spinous Shark (Echinorhinus spinosus) is readily re¬

cognized by the short bulky form of its body, its short tail,

and the large round bony tubercles which are scattered all

over its body, each of which is raised in the middle into a

pointed conical spine. More frequent in the Mediterranean,

it has been found also not very rarely on the English coasts

and near the Cape of Good Hope. It is always living on

the ground, and probably descends to some depth. It does

not seem to exceed a length of 10 feet.

Bathybial Sharks.—Sharks do not appear to have yet

reached the greatest depths of the ocean ; and so far as we

know at present we have to fix the limit of their vertical

distribution at 500 fathoms. Those which we find to have

reached or to pass the 100 fathoms line belong to generic

types which, if they include littoral species, are ground-

sharks,—as we generally find the bottom-feeders of our

littoral fauna much more strongly represented in the deep

sea than the surface swimmers. All belong to two families

only, the Scylliidee, and Spinacidae, the littoral members of

which live for the greater part habitually on the bottom

and probably frequently reach to the 100 fathoms line.

Distinctly bathybial species are two small dog-fishes,—

Spinax granulatus from 120 fathoms, and Scyllium

canescens from 400 fathoms, both on the south-west coast

of South America ; also Centroscyllium granulatum from

245 fathoms in the Antarctic Ocean, whose congener from

the coast of Greenland probably descends to a similar

depth. The sharks which reach the greatest depth

recorded hitherto belong to the genus Centrophorus, of

which some ten species are known, all from deep water in

the North Atlantic, Mediterranean, the Molucca and

Japanese seas. The Japanese species were discovered by

the naturalists of the “Challenger” on the Hyalonema

ground off Inosima in 345 fathoms. Dr E. P. Wright

found G. coelolepis at a still greater depth on the coast of

Portugal. The fishermen of Setubal fish for these sharks

in 400 or 500 fathoms, with a line of some 600 fathoms

in length. “ The sharks caught were from 3 to 4 feet long,

and when they were hauled into the boat fell down into

it like so many dead pigs”; in fact, on being rapidly

withdrawn from the great pressure under which they

lived they were killed, like other deep-sea fishes under

similar circumstances. It is noteworthy that the organiz¬

ation of none of these deep-sea sharks has undergone

such a modification as would lead us to infer that they

arc inhabitants of

great depths.

One of the

most interesting

types of the divi¬

sion of sharks is

the small family

of Notidanidx,

which is external¬

ly distinguished

by the presence

of a single dorsal

fin only, without

spine and oppo¬

site to the anal,

and by having

six or seven wide

branchial open¬

ings. They repre¬

sent an ancient

type, the presence

of which in Ju¬

rassic formations

is shown by teeth

extremely similar

to those of the

living species.

Their skeleton

is notochordal.

Only four species

are known, of

which one (JYoti-

danus griseus) has

now and then

strayed north¬

wards to the

Fig. XG.—Chlamydoselachus anguineus.

English coast. A member of this family has been re¬

cently discovered in Japan, and is so scarce that only

two specimens are known—one in the museum at Cam¬

bridge, U.S., and the other in the British Museum. It

was named by its first describer, S. Garman, Chlamy¬

doselachus anguineus (fig. 16). It resembles somewhat

in shape a conger, and differs from the Notidani proper

by its elongate body, wide lateral and terminal mouth,

extremely wide gill-openings, and peculiarly formed teeth.

The teeth are similar in both jaws, each composed of

three slender curved cusps separated by a pair of rudi¬

mentary points, and with a broad base directed back¬

wards. These teeth resemble some fossils of the Middle

Devonian, described as Cladodus, and North-American

SHARK

same family as the spiked dog-fish, but grows to a much

larger size, specimens 15 feet long being frequently met

Fig. 15.—Dentition of Greenland Shark.

Fig. 14.—Greenland Shark {Lxmargus borealis).

with. The two dorsal fins are small and destitute of

spines. The teeth (fig. 11) in the upper jaw are small,

narrow, conical in shape ; those of the lower flat, arranged

in several series, one on the top of the other, so that only

the uppermost forms the sharp dental edge of the jaw.

The points of

these lower

teeth are so

much turned

aside that the

inner margin

only enters the

dental edge.

The Green¬

land shark is

an inhabitant

of the Arctic

regions, some¬

times straying

to the lati¬

tudes of Great

Britain and of

Cape Cod in

the western Atlantic ; it is one of the greatest enemies of

the whale, which is often found with large pieces bitten

out of the tail by this shark. Its voracity is so great that,

as Scoresby tells us, it is absolutely fearless in the presence

of man whilst engaged in feeding on the carcase of a

whale, and that it will allow itself to be stabbed with a

lance or knife without being driven away.

The Spinous Shark (Echinorhinus spinosus) is readily re¬

cognized by the short bulky form of its body, its short tail,

and the large round bony tubercles which are scattered all

over its body, each of which is raised in the middle into a

pointed conical spine. More frequent in the Mediterranean,

it has been found also not very rarely on the English coasts

and near the Cape of Good Hope. It is always living on

the ground, and probably descends to some depth. It does

not seem to exceed a length of 10 feet.

Bathybial Sharks.—Sharks do not appear to have yet

reached the greatest depths of the ocean ; and so far as we

know at present we have to fix the limit of their vertical

distribution at 500 fathoms. Those which we find to have

reached or to pass the 100 fathoms line belong to generic

types which, if they include littoral species, are ground-

sharks,—as we generally find the bottom-feeders of our

littoral fauna much more strongly represented in the deep

sea than the surface swimmers. All belong to two families

only, the Scylliidee, and Spinacidae, the littoral members of

which live for the greater part habitually on the bottom

and probably frequently reach to the 100 fathoms line.

Distinctly bathybial species are two small dog-fishes,—

Spinax granulatus from 120 fathoms, and Scyllium

canescens from 400 fathoms, both on the south-west coast

of South America ; also Centroscyllium granulatum from

245 fathoms in the Antarctic Ocean, whose congener from

the coast of Greenland probably descends to a similar

depth. The sharks which reach the greatest depth

recorded hitherto belong to the genus Centrophorus, of

which some ten species are known, all from deep water in

the North Atlantic, Mediterranean, the Molucca and

Japanese seas. The Japanese species were discovered by

the naturalists of the “Challenger” on the Hyalonema

ground off Inosima in 345 fathoms. Dr E. P. Wright

found G. coelolepis at a still greater depth on the coast of

Portugal. The fishermen of Setubal fish for these sharks

in 400 or 500 fathoms, with a line of some 600 fathoms

in length. “ The sharks caught were from 3 to 4 feet long,

and when they were hauled into the boat fell down into

it like so many dead pigs”; in fact, on being rapidly

withdrawn from the great pressure under which they

lived they were killed, like other deep-sea fishes under

similar circumstances. It is noteworthy that the organiz¬

ation of none of these deep-sea sharks has undergone

such a modification as would lead us to infer that they

arc inhabitants of

great depths.

One of the

most interesting

types of the divi¬

sion of sharks is

the small family

of Notidanidx,

which is external¬

ly distinguished

by the presence

of a single dorsal

fin only, without

spine and oppo¬

site to the anal,

and by having

six or seven wide

branchial open¬

ings. They repre¬

sent an ancient

type, the presence

of which in Ju¬

rassic formations

is shown by teeth

extremely similar

to those of the

living species.

Their skeleton

is notochordal.

Only four species

are known, of

which one (JYoti-

danus griseus) has

now and then

strayed north¬

wards to the

Fig. XG.—Chlamydoselachus anguineus.

English coast. A member of this family has been re¬

cently discovered in Japan, and is so scarce that only

two specimens are known—one in the museum at Cam¬

bridge, U.S., and the other in the British Museum. It

was named by its first describer, S. Garman, Chlamy¬

doselachus anguineus (fig. 16). It resembles somewhat

in shape a conger, and differs from the Notidani proper

by its elongate body, wide lateral and terminal mouth,

extremely wide gill-openings, and peculiarly formed teeth.

The teeth are similar in both jaws, each composed of

three slender curved cusps separated by a pair of rudi¬

mentary points, and with a broad base directed back¬

wards. These teeth resemble some fossils of the Middle

Devonian, described as Cladodus, and North-American

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (788) Page 778 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193637523 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|