Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(638) Page 628

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

628

SEISMOMETER

proposed by Mr. T. Gray,1 Mr. C. A. Stevenson,2 and others. Prob¬

ably the best form would be that of a light spherical segment

rolling on a level plane base and carrying a heavy bob fixed to it.

To give some stability the bob should be placed so as to bring the

centre of gravity a little under the centre of curvature. The centre

of percussion, somewhat higher than this, would of course be the

steady point, and a multiplying pointer might take the motion

either from it or from any other convenient part of the rolling

piece. All rolling seismometers—including rolling cylinders, which

have been proposed by Mr Gray as single-freedom instruments, to

register one component of horizontal motion—fail to act well,

partly because of the comparatively great frictional or quasi-fric-

tional resistance which is presented to the motion of the free

mass, and partly because, owing to imperfections in the construc¬

tion and want of perfect rigidity in the materials, the ball or cylinder

takes up a position in which there is an objectionably great stability

as regards very small displacements. These objections make the

use of rolling seismometers unadvisable, except perhaps for the

rough measurement of violent earthquakes.

The seismographs which have been described draw a horizontal

plan of the path pursued during an earthquake by a point on the

earth’s surface. They take no note of the relation of the displace¬

ment to time,—an element which is required if we are to form any

estimate of the violence of an earthquake from the record. With

this view a different method of registration is also followed. The

whole movement is resolved into rectilinear components, and these

are separately recorded (by single-freedom seismometers) on a plate

or drum which is kept in continuous movement, so that the record

of each component takes the form of an undulating line, from which

the number, succession, amplitude, velocity, and acceleration of the

component movements can be deduced and the resultant motion

determined. A single steady mass with two degrees of freedom

may still be employed to record, separately, two components of

horizontal motion; but it is generally preferable to provide two

distinct masses, each with one degree of freedom. The principal

instrument of this class is the horizontal pendulum seismograph,3

which has been used to record Japanese earthquakes since 1880.

It consists of two horizontal pendulums, set at right angles to each

other, each supplying a steady point with respect to horizontal

motions transverse to its own length. Each pendulum is pivoted

about two points, on an axis which is nearly vertical, but in¬

clined slightly forwards to give a suitable degree of stability. In

some forms of the instrument the pivoted frame of the pendulum

is light, and the inertia is practically all furnished by a second

piece or bob pivoted on the frame about a vertical axis through

the centre of percussion of the frame. This construction has the

advantage of compactness and of making the position of the steady

point at once determinate. But a simpler construction is to at¬

tach the bob rigidly to the frame. This shifts the steady point

a little way outwards from the position it would have if the bob

were pivoted. In either construction a prolongation of the pendu¬

lum beyond the bob forms a convenient multiplying index. Fig.

or be started into motion by an electric seismoscope when the

earliest indications of an earthquake are felt. The former plan is

practicable only when the instrument can receive careful attend¬

ance and where earthquakes occur often. It has the drawback that

the circle which is drawn by each pointer as the plate revolves

below it gradually broadens, partly because of warping and tempera¬

ture changes in the supports and partly because of actual tilting of

the ground. As an earthquake generally begins with comparatively

insignificant movements, there is not much to object to in having

the plate at rest to begin with, provided a sufficiently sensitive

starting seismoscope be used. A suitable arrangement for this pur¬

pose is one due to Palmieri: a short pendulum hangs over a cup of

mercury, in the centre of which a depression is formed by an iron

pin, whose top is a little lower than the surface of the mercury.

The pendulum ends in a platinum point, which stands clear in the

centre of this depression, but touches the edge whenever a horizontal

movement of the ground takes place, thereby closing the circuit of

an electro-magnet, which starts the clock. In the most recent

form of the horizontal pendulum seismograph the bobs are fixed

to the pivoted frames, and the pointers are arranged to trace their

records side by side. Records with instruments of this class, besides

giving much additional information, agree with those of the duplex

pendulum in show¬

ing that earthquake

motion is a tangle

of waves in all azi¬

muths. This will

be seen by reference

to fig. 6, which shows

a small portion of

g?steeraedthbyUapeairrofFlG- 6j7Rec0rd of earthquake by horizontal

horizontal pendu- Pendulum seismograph; one-third full size.

lums. Contemporary parts of the two records are shown together,

the straight radial lines marking seconds of time. The phases of

the two components are con- n

tinually changing, and when

the two are compounded the

result is a path having the

same characteristics as those of

the diagram in fig. 3. Fig. 7

gives the result of compoundingw

the records of fig. 6 during three

seconds, while the range of move¬

ment was a maximum.

To register the vertical com¬

ponent of earthquake motions

we require to suspend a mass

with vertical freedom. Most ^

ways of doing this give too Fig./.-Result of compounding the

much stability, as, for instance, recor o g. 6.

when a weight is hung from a spiral spring or carried by a hori¬

zontal bar that is fixed to a wall or table

by a flexible spring joint. This last is the

vertical motion seis¬

mometer which was

used by the British

Association Commit¬

tee at Comrie inl842.

Another form, me¬

chanically equivalent

to this, is a weighted

horizontal bar, pivot¬

ed on a fixed hori¬

zontal fulcrum, and

held up by a spiral

spring, stretched

from a point near

the fulcrum to a

fixed support above.

This mode of suspen¬

sion is still too stable,

though less so than

I'wAv

3

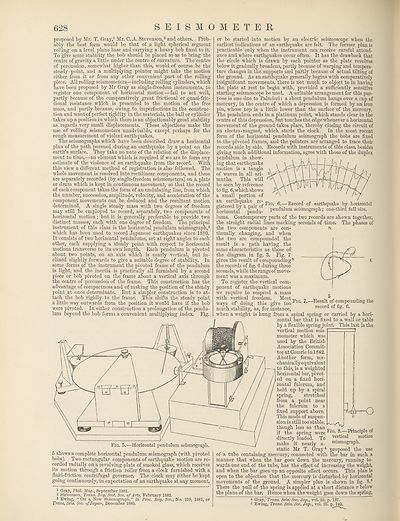

Fig. 5.—Horizontal pendulum seismograph.

5 shows a complete horizontal pendulum seismograph (with pivoted

bobs). Two rectangular components of earthquake motion are re¬

corded radially on a revolving plate of smoked glass, which receives

its motion through a friction roller from a clock furnished with a

fluid-friction centrifugal governor. The clock may either be kept

going continuously, in expectation of an earthquake at any moment,

1 Gray, Phil. Mag., September 1881.

2 Stevenson, Trans. Roy. Scot. Soc. of Arts, February 1882.

3 Ewing, “On a New Seismograph,” in Proc. Roy. Soc., No. 210, 1881, or

Trans. Seis. Soc. of Japan, December 1880.

Fig. 8.—Principle of

directly Ibaded. To verticnl ,motion

make it nearly a- seismograph,

static Mr T. Gray4 proposed the use

of a tube containing mercury, connected with the bar in such a

manner that when the bar goes down the mercury, running to¬

wards one end of the tube, has the effect of increasing the weight,

and when the bar goes up an opposite effect occurs. This plan is

open to the objection that the mercury is disturbed by horizontal

movements of the ground. A simpler plan is shown in fig. 8.5

There the pull of the spring is applied at a short distance v below

the plane of the bar. Hence when the weight goes down the spring,

4 Gray, Trans. Seis. Soc. Jap., vol. iii. p. 137.

5 Ewing, Trans. Seis. Soc. Jap., vol. iii. p. 140.

SEISMOMETER

proposed by Mr. T. Gray,1 Mr. C. A. Stevenson,2 and others. Prob¬

ably the best form would be that of a light spherical segment

rolling on a level plane base and carrying a heavy bob fixed to it.

To give some stability the bob should be placed so as to bring the

centre of gravity a little under the centre of curvature. The centre

of percussion, somewhat higher than this, would of course be the

steady point, and a multiplying pointer might take the motion

either from it or from any other convenient part of the rolling

piece. All rolling seismometers—including rolling cylinders, which

have been proposed by Mr Gray as single-freedom instruments, to

register one component of horizontal motion—fail to act well,

partly because of the comparatively great frictional or quasi-fric-

tional resistance which is presented to the motion of the free

mass, and partly because, owing to imperfections in the construc¬

tion and want of perfect rigidity in the materials, the ball or cylinder

takes up a position in which there is an objectionably great stability

as regards very small displacements. These objections make the

use of rolling seismometers unadvisable, except perhaps for the

rough measurement of violent earthquakes.

The seismographs which have been described draw a horizontal

plan of the path pursued during an earthquake by a point on the

earth’s surface. They take no note of the relation of the displace¬

ment to time,—an element which is required if we are to form any

estimate of the violence of an earthquake from the record. With

this view a different method of registration is also followed. The

whole movement is resolved into rectilinear components, and these

are separately recorded (by single-freedom seismometers) on a plate

or drum which is kept in continuous movement, so that the record

of each component takes the form of an undulating line, from which

the number, succession, amplitude, velocity, and acceleration of the

component movements can be deduced and the resultant motion

determined. A single steady mass with two degrees of freedom

may still be employed to record, separately, two components of

horizontal motion; but it is generally preferable to provide two

distinct masses, each with one degree of freedom. The principal

instrument of this class is the horizontal pendulum seismograph,3

which has been used to record Japanese earthquakes since 1880.

It consists of two horizontal pendulums, set at right angles to each

other, each supplying a steady point with respect to horizontal

motions transverse to its own length. Each pendulum is pivoted

about two points, on an axis which is nearly vertical, but in¬

clined slightly forwards to give a suitable degree of stability. In

some forms of the instrument the pivoted frame of the pendulum

is light, and the inertia is practically all furnished by a second

piece or bob pivoted on the frame about a vertical axis through

the centre of percussion of the frame. This construction has the

advantage of compactness and of making the position of the steady

point at once determinate. But a simpler construction is to at¬

tach the bob rigidly to the frame. This shifts the steady point

a little way outwards from the position it would have if the bob

were pivoted. In either construction a prolongation of the pendu¬

lum beyond the bob forms a convenient multiplying index. Fig.

or be started into motion by an electric seismoscope when the

earliest indications of an earthquake are felt. The former plan is

practicable only when the instrument can receive careful attend¬

ance and where earthquakes occur often. It has the drawback that

the circle which is drawn by each pointer as the plate revolves

below it gradually broadens, partly because of warping and tempera¬

ture changes in the supports and partly because of actual tilting of

the ground. As an earthquake generally begins with comparatively

insignificant movements, there is not much to object to in having

the plate at rest to begin with, provided a sufficiently sensitive

starting seismoscope be used. A suitable arrangement for this pur¬

pose is one due to Palmieri: a short pendulum hangs over a cup of

mercury, in the centre of which a depression is formed by an iron

pin, whose top is a little lower than the surface of the mercury.

The pendulum ends in a platinum point, which stands clear in the

centre of this depression, but touches the edge whenever a horizontal

movement of the ground takes place, thereby closing the circuit of

an electro-magnet, which starts the clock. In the most recent

form of the horizontal pendulum seismograph the bobs are fixed

to the pivoted frames, and the pointers are arranged to trace their

records side by side. Records with instruments of this class, besides

giving much additional information, agree with those of the duplex

pendulum in show¬

ing that earthquake

motion is a tangle

of waves in all azi¬

muths. This will

be seen by reference

to fig. 6, which shows

a small portion of

g?steeraedthbyUapeairrofFlG- 6j7Rec0rd of earthquake by horizontal

horizontal pendu- Pendulum seismograph; one-third full size.

lums. Contemporary parts of the two records are shown together,

the straight radial lines marking seconds of time. The phases of

the two components are con- n

tinually changing, and when

the two are compounded the

result is a path having the

same characteristics as those of

the diagram in fig. 3. Fig. 7

gives the result of compoundingw

the records of fig. 6 during three

seconds, while the range of move¬

ment was a maximum.

To register the vertical com¬

ponent of earthquake motions

we require to suspend a mass

with vertical freedom. Most ^

ways of doing this give too Fig./.-Result of compounding the

much stability, as, for instance, recor o g. 6.

when a weight is hung from a spiral spring or carried by a hori¬

zontal bar that is fixed to a wall or table

by a flexible spring joint. This last is the

vertical motion seis¬

mometer which was

used by the British

Association Commit¬

tee at Comrie inl842.

Another form, me¬

chanically equivalent

to this, is a weighted

horizontal bar, pivot¬

ed on a fixed hori¬

zontal fulcrum, and

held up by a spiral

spring, stretched

from a point near

the fulcrum to a

fixed support above.

This mode of suspen¬

sion is still too stable,

though less so than

I'wAv

3

Fig. 5.—Horizontal pendulum seismograph.

5 shows a complete horizontal pendulum seismograph (with pivoted

bobs). Two rectangular components of earthquake motion are re¬

corded radially on a revolving plate of smoked glass, which receives

its motion through a friction roller from a clock furnished with a

fluid-friction centrifugal governor. The clock may either be kept

going continuously, in expectation of an earthquake at any moment,

1 Gray, Phil. Mag., September 1881.

2 Stevenson, Trans. Roy. Scot. Soc. of Arts, February 1882.

3 Ewing, “On a New Seismograph,” in Proc. Roy. Soc., No. 210, 1881, or

Trans. Seis. Soc. of Japan, December 1880.

Fig. 8.—Principle of

directly Ibaded. To verticnl ,motion

make it nearly a- seismograph,

static Mr T. Gray4 proposed the use

of a tube containing mercury, connected with the bar in such a

manner that when the bar goes down the mercury, running to¬

wards one end of the tube, has the effect of increasing the weight,

and when the bar goes up an opposite effect occurs. This plan is

open to the objection that the mercury is disturbed by horizontal

movements of the ground. A simpler plan is shown in fig. 8.5

There the pull of the spring is applied at a short distance v below

the plane of the bar. Hence when the weight goes down the spring,

4 Gray, Trans. Seis. Soc. Jap., vol. iii. p. 137.

5 Ewing, Trans. Seis. Soc. Jap., vol. iii. p. 140.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (638) Page 628 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193635573 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|