Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(600) Page 590

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

590

SEAMANSHIP

at high speed in thick weather being thereby much in¬

creased. Through the want of masts and sails there is a

probability of total loss by drifting helplessly on a lee

shore during a gale, or by foundering “ in the trough of

the sea.” In spite of her monstrous size (22,000 tons),

the “Great Eastern,” in 1863 or 1864, with her six com¬

paratively small masts and weak sails was, after the loss

of her rudder, very roughly used by the waves striking

her full on the side. She was in the position which is

expressed by the common sea-phrase “wallowing in the

trough of the sea,” from which her crew had no power to

extricate her. A smaller vessel deeply laden in such a

position would most probably have foundered, leaving no

one to tell the tale. Too much stress is laid upon the re¬

tardation caused by masts and rigging when steaming

head to wind; it is the pitching and plunging motion of

the ship into a succession of waves that principally retards

her speed. If the waves are approaching at the rate of 10

miles an hour and the ship is steaming against them at a

similar rate, they will strike the bows with a force equal

to 20 miles an hour. When a ship is steaming through

comparatively smooth water (sheltered by land) against a

gale of wind, her speed is but little reduced by the force

of the wind alone, when other circumstances admit of her

working full power. Storm-sails only require short masts,

but these and the canvas they support should be strong,

which is not the case in the merchant service generally.

Duties of Every seaman is expected to be thoroughly acquainted

a sea- with the rigging of the vessel in which he serves, and

man. when in charge he should frequently examine every part,

to see that it is efficiently performing the duty assigned to

it, being neither too taut nor too slack, nor suffering from

chafing, wet, or other injury. He should be capable of

repairing or replacing any part with his own hand if

necessary and of teaching others how to do so. He need

not necessarily be a navigator, though a good navigator

must be a seaman; nor is it necessary that a seaman

should be a shipbuilder, a mast-maker, a rope-maker, or a

sail-maker, but he should possess a general knowledge of

each art, especially the last; every able seaman should be

able to sew a seam and assist the ship’s sail-maker in

repairing sails. It is greatly to be regretted that various

circumstances have brought about such a change in the

system of rigging ships, in both the British navy and the

mercantile marine, that those who sail in them seldom see

it done. Young officers were in former times frequently

entrusted with the charge of day watches, during which

they would give the necessary orders for making, shorten¬

ing, or trimming sails, perhaps even tacking and wearing.

That practice gave confidence and quickened the desire to

learn more; it was more frequently done in small than in

large ships. The general adoption of the steam-engine in

ships has not only diminished the value of sail-power but

of seamanship also, and has produced such a change in

the rig that instead of masts and yards we find only two

or three poles. In the British navy so many new sciences

have been introduced that seamanship takes but a low

place among them at the examination of a midshipman,

who has had but little boat duty and probably found the

discussion of seamanship in his mess-place contrary to

rule. The rapidity with which all sail and mast drill is

executed, combined with the perfection of the “ station

bill,” renders it worse than useless as a means of teaching,

as it gives a false confidence which fails in the hour of

necessity, when the accustomed routine is thrown out by a

sail actually splitting to pieces or a spar snapping. The

fact that the same men perpetually do the same thing must

tend greatly to render each evolution quick so long as

every one is in his accustomed place, but sickness or the

absence of a party from duty will disorganize the ship for

some time, as the general usefulness of the men has been

cramped. Sail drill in harbour is open to grave objec¬

tions : unless in a tide-way, the ship must be invariably

head to wind; for reefing and furling the yards are laid

square, consequently flat aback ; both earings are hauled

out at once, and as it is only for exercise they are only

half secured. Even when reefing top-sails at sea either for

exercise or of necessity in company with other ships, the

yards are laid square to enable the men to get readily on

the weather-side; therefore, if on a wind, the sail must re¬

main aback or the ship must be kept away till the wind is

on the beam in order to shake the sail.

The foundation of all teaching of seamanship must be a Knots,

knowledge of the knots, bends, and splices, and their use hitches,

in the various parts of the rigging and equipment of a!?ends>

ship.1 Some knots, bends, and hitches are intended to afford C’

security as long as desired, and then to be easily disengaged.

Other knots, splices, and seizings are of a more permanent

character, generally continuing as long as the rope will last.

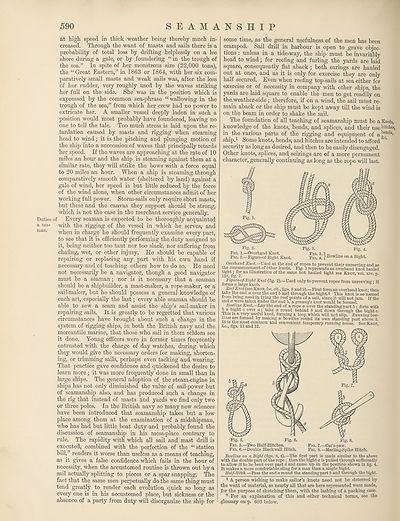

Fig. 2. Fig. 3. Fig. 4.

Fig. 1.—Overhand Knot. Fig. 3 ) t, ..

Fig. 2.—Figure-of-Eight Knot. Fig. 4. ) Bowlllle on a Bight.

Overhand Knot. Used at the end of ropes to prevent their unreeving and as

the commencement of other knots. Fig. 1 represents an overhand knot hauled

128 fi 7 an lllustration of tlle same not hauled tight see Knot, vol. xiv. p.

Figure-of-Eight Knot (flg. 2).—Used only to prevent ropes from unreevins : it

forms a large knob.

Reef Knot (see Ks or, loc. cit., figs. 8 and 9).—First form an overhand knot; then

take the end a over the end 6 and through the bight.a This knot is so named

from being used in tying the reef points of a sail, since it will not jam. If the

end a were taken under the end b, a granny’s knot would be formed.

Bowline Knot.—Lay the end of a rope a over the standing part 6 ; form with

6 a bight c over a; take a round behind 6 and down through the bight c.

This is a very useful knot, forming a loop which will not slip. Running bow¬

lines are formed by making a bowline round its own standing part above b.

It is the most common and convenient temporary running noose. See Knot,

/. /» fi era 11 a n H 1 9

Fig. 5.—Two Half-Hitches. Fig. 7.—Cat’s-paw.

Fig. 6.—Double Blackwall Hitch. Fig. 8.—Marling-Spike Hitch.

Bowline on a Bight (figs. 3, 4).—The first part is made similar to the above

with the double part of the rope ; then the bight a is pulled through sufficiently

to allow it to be bent over past d and come up in the position shown in fig. 4.

It makes a more comfortable sling for a man than a single bight.

Half-Hitch.—Pass the end a round the standing part b and through the bight.

1 A person wishing to make sailor’s knots need not be deterred by

the want of material, as nearly all that are here represented were made,

for the purpose of sketching them, with the lashing of a packing case.

2 For an explanation of this and other technical terms, see the

glossary on p. 603 below.

SEAMANSHIP

at high speed in thick weather being thereby much in¬

creased. Through the want of masts and sails there is a

probability of total loss by drifting helplessly on a lee

shore during a gale, or by foundering “ in the trough of

the sea.” In spite of her monstrous size (22,000 tons),

the “Great Eastern,” in 1863 or 1864, with her six com¬

paratively small masts and weak sails was, after the loss

of her rudder, very roughly used by the waves striking

her full on the side. She was in the position which is

expressed by the common sea-phrase “wallowing in the

trough of the sea,” from which her crew had no power to

extricate her. A smaller vessel deeply laden in such a

position would most probably have foundered, leaving no

one to tell the tale. Too much stress is laid upon the re¬

tardation caused by masts and rigging when steaming

head to wind; it is the pitching and plunging motion of

the ship into a succession of waves that principally retards

her speed. If the waves are approaching at the rate of 10

miles an hour and the ship is steaming against them at a

similar rate, they will strike the bows with a force equal

to 20 miles an hour. When a ship is steaming through

comparatively smooth water (sheltered by land) against a

gale of wind, her speed is but little reduced by the force

of the wind alone, when other circumstances admit of her

working full power. Storm-sails only require short masts,

but these and the canvas they support should be strong,

which is not the case in the merchant service generally.

Duties of Every seaman is expected to be thoroughly acquainted

a sea- with the rigging of the vessel in which he serves, and

man. when in charge he should frequently examine every part,

to see that it is efficiently performing the duty assigned to

it, being neither too taut nor too slack, nor suffering from

chafing, wet, or other injury. He should be capable of

repairing or replacing any part with his own hand if

necessary and of teaching others how to do so. He need

not necessarily be a navigator, though a good navigator

must be a seaman; nor is it necessary that a seaman

should be a shipbuilder, a mast-maker, a rope-maker, or a

sail-maker, but he should possess a general knowledge of

each art, especially the last; every able seaman should be

able to sew a seam and assist the ship’s sail-maker in

repairing sails. It is greatly to be regretted that various

circumstances have brought about such a change in the

system of rigging ships, in both the British navy and the

mercantile marine, that those who sail in them seldom see

it done. Young officers were in former times frequently

entrusted with the charge of day watches, during which

they would give the necessary orders for making, shorten¬

ing, or trimming sails, perhaps even tacking and wearing.

That practice gave confidence and quickened the desire to

learn more; it was more frequently done in small than in

large ships. The general adoption of the steam-engine in

ships has not only diminished the value of sail-power but

of seamanship also, and has produced such a change in

the rig that instead of masts and yards we find only two

or three poles. In the British navy so many new sciences

have been introduced that seamanship takes but a low

place among them at the examination of a midshipman,

who has had but little boat duty and probably found the

discussion of seamanship in his mess-place contrary to

rule. The rapidity with which all sail and mast drill is

executed, combined with the perfection of the “ station

bill,” renders it worse than useless as a means of teaching,

as it gives a false confidence which fails in the hour of

necessity, when the accustomed routine is thrown out by a

sail actually splitting to pieces or a spar snapping. The

fact that the same men perpetually do the same thing must

tend greatly to render each evolution quick so long as

every one is in his accustomed place, but sickness or the

absence of a party from duty will disorganize the ship for

some time, as the general usefulness of the men has been

cramped. Sail drill in harbour is open to grave objec¬

tions : unless in a tide-way, the ship must be invariably

head to wind; for reefing and furling the yards are laid

square, consequently flat aback ; both earings are hauled

out at once, and as it is only for exercise they are only

half secured. Even when reefing top-sails at sea either for

exercise or of necessity in company with other ships, the

yards are laid square to enable the men to get readily on

the weather-side; therefore, if on a wind, the sail must re¬

main aback or the ship must be kept away till the wind is

on the beam in order to shake the sail.

The foundation of all teaching of seamanship must be a Knots,

knowledge of the knots, bends, and splices, and their use hitches,

in the various parts of the rigging and equipment of a!?ends>

ship.1 Some knots, bends, and hitches are intended to afford C’

security as long as desired, and then to be easily disengaged.

Other knots, splices, and seizings are of a more permanent

character, generally continuing as long as the rope will last.

Fig. 2. Fig. 3. Fig. 4.

Fig. 1.—Overhand Knot. Fig. 3 ) t, ..

Fig. 2.—Figure-of-Eight Knot. Fig. 4. ) Bowlllle on a Bight.

Overhand Knot. Used at the end of ropes to prevent their unreeving and as

the commencement of other knots. Fig. 1 represents an overhand knot hauled

128 fi 7 an lllustration of tlle same not hauled tight see Knot, vol. xiv. p.

Figure-of-Eight Knot (flg. 2).—Used only to prevent ropes from unreevins : it

forms a large knob.

Reef Knot (see Ks or, loc. cit., figs. 8 and 9).—First form an overhand knot; then

take the end a over the end 6 and through the bight.a This knot is so named

from being used in tying the reef points of a sail, since it will not jam. If the

end a were taken under the end b, a granny’s knot would be formed.

Bowline Knot.—Lay the end of a rope a over the standing part 6 ; form with

6 a bight c over a; take a round behind 6 and down through the bight c.

This is a very useful knot, forming a loop which will not slip. Running bow¬

lines are formed by making a bowline round its own standing part above b.

It is the most common and convenient temporary running noose. See Knot,

/. /» fi era 11 a n H 1 9

Fig. 5.—Two Half-Hitches. Fig. 7.—Cat’s-paw.

Fig. 6.—Double Blackwall Hitch. Fig. 8.—Marling-Spike Hitch.

Bowline on a Bight (figs. 3, 4).—The first part is made similar to the above

with the double part of the rope ; then the bight a is pulled through sufficiently

to allow it to be bent over past d and come up in the position shown in fig. 4.

It makes a more comfortable sling for a man than a single bight.

Half-Hitch.—Pass the end a round the standing part b and through the bight.

1 A person wishing to make sailor’s knots need not be deterred by

the want of material, as nearly all that are here represented were made,

for the purpose of sketching them, with the lashing of a packing case.

2 For an explanation of this and other technical terms, see the

glossary on p. 603 below.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (600) Page 590 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193635079 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|