Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(591) Page 581

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

581

SEAL

common seal (Phoca vitulina) is a constant resident in all

suitable localities round the Scottish, Irish, and English

coasts, from which it has not been driven away by the

molestations of man. Although, naturally, the most se¬

cluded and out-of-the-way spots are selected as their

habitual dwelling-places, there are few localities where they

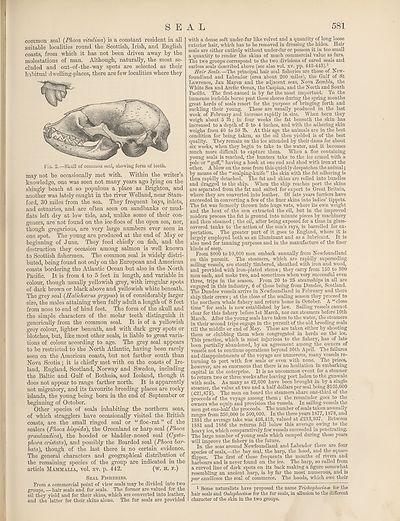

Fig. 2.—Skull of common seal, showing form of teeth.

may not be occasionally met with. Within the writer’s

knowledge, one was seen not many years ago lying on the

shingly beach at so populous a place as Brighton, and

another was lately caught in the river Welland, near Stam¬

ford, 30 miles from the sea. They frequent bays, inlets,

and estuaries, and are often seen on sandbanks or mud¬

flats left dry at low tide, and, unlike some of their con¬

geners, are not found on the ice-floes of the open sea, nor,

though gregarious, are very large numbers ever seen in

one spot. The young are produced at the end of May or

beginning of June. They feed chiefly on fish, and the

destruction they occasion among salmon is well known

to Scottish fishermen. The common seal is widely distri¬

buted, being found not only on the European and American

coasts bordering the Atlantic Ocean but also in the North

Pacific. It is from 4 to 5 feet in length, and variable in

colour, though usually yellowish grey, with irregular spots

of dark brown or black above and yellowish white beneath.

The grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) is of considerably larger

size, the males attaining when fully adult a length of 8 feet

from nose to end of hind feet. The form of the skull and

the simple characters of the molar teeth distinguish it

generically from the common seal. It is of a yellowish

grey colour, lighter beneath, and with dark grey spots or

blotches, but, like most other seals, is liable to great varia¬

tions of colour according to age. The grey seal appears

to be restricted to the North Atlantic, having been rarely

seen on the American coasts, but not farther south than

Nova Scotia; it is chiefly met with on the coasts of Ire¬

land, England, Scotland, Norway and Sweden, including

the Baltic and Gulf of Bothnia, and Iceland, though it

does not appear to range farther north. It is apparently

not migratory, and its favourite breeding places are rocky

islands, the young being born in the end of September or

beginning of October.

Other species of seals inhabiting the northern seas,

of which stragglers have occasionally visited the British

coasts, are the small ringed seal or “ floe-rat ” of the

sealers {Phoca hispida), the Greenland or harp seal {Phoca

groenlandica), the hooded or bladder-nosed seal {Cysto-

phora cristata), and possibly the Bearded seal {Phoca bar-

bata), though of the last there is no certain evidence.

The general characters and geographical distribution of

the remaining species of the group are indicated in the

article Mammalia, vol. xv. p. 442. (w. h. f.)

Seal Fisheries.

From a commercial point of view seals may be divided into two

groups, —hair seals and fur seals. The former are valued for the

oil they yield and for their skins, which are converted into leather,

and the latter for their skins alone. The fur seals are provided

with a dense soft under-fur like velvet and a quantity of long loose

exterior hair, which has to he removed in dressing the hides. Hair

seals are either entirely without under-fur or possess it in too small

a quantity to render the skins of much commercial value as furs.

The two groups correspond to the two divisions of eared seals and

earless seals described above (see also vol. xv. pp. 442-443).1

Hair Seals.—The principal hair seal fisheries are those of New¬

foundland and Labrador (area about 200 miles), the Gulf of St

Lawrence, Jan Mayen and the adjacent seas, Nova Zembla, the

White Sea and Arctic Ocean, the Caspian, and the North and South

Pacific. The first-named is by far the most important. To the

immense icefields borne past these shores during the spring months

great herds of seals resort for the purpose of bringing forth and

suckling their young. These are usually produced in the last

week of February and increase rapidly in size. When born they

weigh about 5 lb; in four weeks the fat beneath the skin has

increased to a depth of 3 to 4 inches, and with the adhering skin

weighs from 40 to 50 lb. At this age the animals are in the best

condition for being taken, as the oil then yielded is of the best

quality. They remain on the ice attended by their dams for about

six weeks, when they begin to take to the water, and it becomes

much more difficult to capture them. When a floe containing

young seals is reached, the hunters take to the ice armed with a

pole or “gaff,” having a hook at one end and shod with iron at the

other. A blow on the nose from this quickly despatches the animal;

by means of the “ scalping-knife ” the skin with the fat adhering is

then rapidly detached. The fat and skins are rolled into bundles

and dragged to the ship. When the ship reaches port the skins

are separated from the fat and salted for export to Great Britain,

where they are converted into leather. Of late years furriers have

succeeded in converting a few of the finer skins into ladies’ tippets.

The fat was formerly thrown into huge vats, where its own weight

and the heat of the sun extracted the oil, but in the improved

modern process the fat is ground into minute pieces by machinery

and then steamed ; the oil, after being exposed for a time in glass-

covered tanks to the action of the sun’s rays, is barrelled for ex¬

portation. The greater part of it goes to England,_ where it is

largely employed both as an illuminant and as a lubricant. It is

also used for tanning purposes and in the manufacture of the finer

kinds of soap.

From 8000 to 10,000 men embark annually from Newfoundland

on this pursuit. The steamers, which are rapidly superseding

sailing vessels, are stoutly timbered, sheathed with iron and wood,

and provided with iron-plated stems ; they carry from 150 to 300

men each, and make two, and sometimes when very successful even

three, trips in the season. From 20 to 25 steamships in all are

engaged in this industry, 6 of these being from Dundee, Scotland.

The Dundee vessels arrive in Newfoundland in February and there

ship their crews ; at the close of the sealing season they proceed to

the northern whale fishery and return home in October. A “ close

time ” for seals is now established by law. Sailing vessels cannot

clear for this fishery before 1st March, nor can steamers before 10th

March. After the young seals have taken to the water, the steamers

in their second trips engage in the pursuit of the old breeding seals

till the middle or end of May. These are taken either by shooting

them or clubbing them when congregated in herds on the ice.

This practice, which is most injurious to the fishery, has of late

been partially abandoned, by an agreement among the owners of

vessels not to continue operations beyond 30th April. The failures

and disappointments of the voyage are numerous, many vessels re¬

turning to port with few seals or even with none. The prizes,

however, are so enormous that there is no hesitation in embarking

capital in the enterprise. It is no uncommon event for a steamer

to return two or three weeks after leaving port laden to the gunwale

with seals. As many as 42,000 have been brought in by a single

steamer, the value at two and a half dollars per seal being $105,000

(£21,875). The men on board the steamers share one-third of the

proceeds of the voyage among them; the remainder goes to the

owners who equip and provision the vessels. In sailing vessels the

men get one-half the proceeds. The number of seals taken annually

rano-es from 350,000 to 500,000. In the three years 1877,1878, and

1881 the average take was 436,413, valued at £213,937. Between

1881 and 1886 the returns fell below this average^ owing to the

heavy ice, which comparatively few vessels succeeded in penetrating.

The large number of young seals which escaped during these years

will improve the fishery in the future.

In the seas around Newfoundland and Labrador there are four

species of seals,—the bay seal, the harp, the hood, and the square

flipper. The first of these frequents the mouths of rivers and

harbours and is never found on the ice. The harp, so called from

a curved line of dark spots on its back making a figure somewhat

resembling an ancient harp, is by far the most numerous, and is

par excellence the seal of commerce. The hoods, which owe their

1 Some naturalists have proposed the name Trichophocinee for the

hair seals and Oulophocinse for the fur seals, in allusion to the different

character of the skin in the two groups.

SEAL

common seal (Phoca vitulina) is a constant resident in all

suitable localities round the Scottish, Irish, and English

coasts, from which it has not been driven away by the

molestations of man. Although, naturally, the most se¬

cluded and out-of-the-way spots are selected as their

habitual dwelling-places, there are few localities where they

Fig. 2.—Skull of common seal, showing form of teeth.

may not be occasionally met with. Within the writer’s

knowledge, one was seen not many years ago lying on the

shingly beach at so populous a place as Brighton, and

another was lately caught in the river Welland, near Stam¬

ford, 30 miles from the sea. They frequent bays, inlets,

and estuaries, and are often seen on sandbanks or mud¬

flats left dry at low tide, and, unlike some of their con¬

geners, are not found on the ice-floes of the open sea, nor,

though gregarious, are very large numbers ever seen in

one spot. The young are produced at the end of May or

beginning of June. They feed chiefly on fish, and the

destruction they occasion among salmon is well known

to Scottish fishermen. The common seal is widely distri¬

buted, being found not only on the European and American

coasts bordering the Atlantic Ocean but also in the North

Pacific. It is from 4 to 5 feet in length, and variable in

colour, though usually yellowish grey, with irregular spots

of dark brown or black above and yellowish white beneath.

The grey seal (Halichoerus grypus) is of considerably larger

size, the males attaining when fully adult a length of 8 feet

from nose to end of hind feet. The form of the skull and

the simple characters of the molar teeth distinguish it

generically from the common seal. It is of a yellowish

grey colour, lighter beneath, and with dark grey spots or

blotches, but, like most other seals, is liable to great varia¬

tions of colour according to age. The grey seal appears

to be restricted to the North Atlantic, having been rarely

seen on the American coasts, but not farther south than

Nova Scotia; it is chiefly met with on the coasts of Ire¬

land, England, Scotland, Norway and Sweden, including

the Baltic and Gulf of Bothnia, and Iceland, though it

does not appear to range farther north. It is apparently

not migratory, and its favourite breeding places are rocky

islands, the young being born in the end of September or

beginning of October.

Other species of seals inhabiting the northern seas,

of which stragglers have occasionally visited the British

coasts, are the small ringed seal or “ floe-rat ” of the

sealers {Phoca hispida), the Greenland or harp seal {Phoca

groenlandica), the hooded or bladder-nosed seal {Cysto-

phora cristata), and possibly the Bearded seal {Phoca bar-

bata), though of the last there is no certain evidence.

The general characters and geographical distribution of

the remaining species of the group are indicated in the

article Mammalia, vol. xv. p. 442. (w. h. f.)

Seal Fisheries.

From a commercial point of view seals may be divided into two

groups, —hair seals and fur seals. The former are valued for the

oil they yield and for their skins, which are converted into leather,

and the latter for their skins alone. The fur seals are provided

with a dense soft under-fur like velvet and a quantity of long loose

exterior hair, which has to he removed in dressing the hides. Hair

seals are either entirely without under-fur or possess it in too small

a quantity to render the skins of much commercial value as furs.

The two groups correspond to the two divisions of eared seals and

earless seals described above (see also vol. xv. pp. 442-443).1

Hair Seals.—The principal hair seal fisheries are those of New¬

foundland and Labrador (area about 200 miles), the Gulf of St

Lawrence, Jan Mayen and the adjacent seas, Nova Zembla, the

White Sea and Arctic Ocean, the Caspian, and the North and South

Pacific. The first-named is by far the most important. To the

immense icefields borne past these shores during the spring months

great herds of seals resort for the purpose of bringing forth and

suckling their young. These are usually produced in the last

week of February and increase rapidly in size. When born they

weigh about 5 lb; in four weeks the fat beneath the skin has

increased to a depth of 3 to 4 inches, and with the adhering skin

weighs from 40 to 50 lb. At this age the animals are in the best

condition for being taken, as the oil then yielded is of the best

quality. They remain on the ice attended by their dams for about

six weeks, when they begin to take to the water, and it becomes

much more difficult to capture them. When a floe containing

young seals is reached, the hunters take to the ice armed with a

pole or “gaff,” having a hook at one end and shod with iron at the

other. A blow on the nose from this quickly despatches the animal;

by means of the “ scalping-knife ” the skin with the fat adhering is

then rapidly detached. The fat and skins are rolled into bundles

and dragged to the ship. When the ship reaches port the skins

are separated from the fat and salted for export to Great Britain,

where they are converted into leather. Of late years furriers have

succeeded in converting a few of the finer skins into ladies’ tippets.

The fat was formerly thrown into huge vats, where its own weight

and the heat of the sun extracted the oil, but in the improved

modern process the fat is ground into minute pieces by machinery

and then steamed ; the oil, after being exposed for a time in glass-

covered tanks to the action of the sun’s rays, is barrelled for ex¬

portation. The greater part of it goes to England,_ where it is

largely employed both as an illuminant and as a lubricant. It is

also used for tanning purposes and in the manufacture of the finer

kinds of soap.

From 8000 to 10,000 men embark annually from Newfoundland

on this pursuit. The steamers, which are rapidly superseding

sailing vessels, are stoutly timbered, sheathed with iron and wood,

and provided with iron-plated stems ; they carry from 150 to 300

men each, and make two, and sometimes when very successful even

three, trips in the season. From 20 to 25 steamships in all are

engaged in this industry, 6 of these being from Dundee, Scotland.

The Dundee vessels arrive in Newfoundland in February and there

ship their crews ; at the close of the sealing season they proceed to

the northern whale fishery and return home in October. A “ close

time ” for seals is now established by law. Sailing vessels cannot

clear for this fishery before 1st March, nor can steamers before 10th

March. After the young seals have taken to the water, the steamers

in their second trips engage in the pursuit of the old breeding seals

till the middle or end of May. These are taken either by shooting

them or clubbing them when congregated in herds on the ice.

This practice, which is most injurious to the fishery, has of late

been partially abandoned, by an agreement among the owners of

vessels not to continue operations beyond 30th April. The failures

and disappointments of the voyage are numerous, many vessels re¬

turning to port with few seals or even with none. The prizes,

however, are so enormous that there is no hesitation in embarking

capital in the enterprise. It is no uncommon event for a steamer

to return two or three weeks after leaving port laden to the gunwale

with seals. As many as 42,000 have been brought in by a single

steamer, the value at two and a half dollars per seal being $105,000

(£21,875). The men on board the steamers share one-third of the

proceeds of the voyage among them; the remainder goes to the

owners who equip and provision the vessels. In sailing vessels the

men get one-half the proceeds. The number of seals taken annually

rano-es from 350,000 to 500,000. In the three years 1877,1878, and

1881 the average take was 436,413, valued at £213,937. Between

1881 and 1886 the returns fell below this average^ owing to the

heavy ice, which comparatively few vessels succeeded in penetrating.

The large number of young seals which escaped during these years

will improve the fishery in the future.

In the seas around Newfoundland and Labrador there are four

species of seals,—the bay seal, the harp, the hood, and the square

flipper. The first of these frequents the mouths of rivers and

harbours and is never found on the ice. The harp, so called from

a curved line of dark spots on its back making a figure somewhat

resembling an ancient harp, is by far the most numerous, and is

par excellence the seal of commerce. The hoods, which owe their

1 Some naturalists have proposed the name Trichophocinee for the

hair seals and Oulophocinse for the fur seals, in allusion to the different

character of the skin in the two groups.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (591) Page 581 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634962 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|