Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(589) Page 579

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

579

S E A —S E A

lation. Winds and differences of barometric pressure are,

as in inland seas, great factors in producing variable

currents. (See Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Mediterranean

Sea, Red Sea, &c.)

Partially Enclosed Seas may be (a) comparatively shallow

irregular channels through which strong tides sweep, or (b)

ocean basins cut off by barriers barely rising to the surface,

or remaining permanently submerged, in which case there

may be no break of continuity in the ocean surface to indi¬

cate the sea. Seas of the first description are related to

shallow enclosed seas, but are much affected by tides and

ocean currents; the principal are the Kara Sea of the Arctic

Ocean, Baffin Bay and North Sea of the Atlantic, Behring

Sea and Japan Sea of the Pacific. They are subject to

considerable temperature changes owing to their proximity

to land. Seas coming under the second category combine

the peculiarities of the open ocean and of deep inland seas.

The Caribbean Sea of the Atlantic, the China Sea, Java

Sea, and numerous small seas of the eastern archipelago

of the Pacific are the best examples. Their chief peculi¬

arity is that the temperature of the water instead of falling

uniformly to the bottom becomes stationary at some inter¬

mediate position corresponding to the top of the barrier.

They are usually very deep. (See North Sea, Norwegian

Sea, and Pacific Ocean.)

Other Seas.—Coral Sea, Arabian Sea, Sea of Bengal, are

names, now dropping out of use, to designate parts of the

ocean. “Sargasso Sea” is an expression devoid of geo¬

graphical meaning (see Atlantic Ocean, vol. iii. p. 20).

Firths and Estuaries.—A river entering the sea by a

short estuary flows over the surface, freshening it to a con¬

siderable extent, and, if the force of its current is not too

great, the rising tide slowly forces a wedge of sea water up

between river and river bed, withdrawing it rapidly when

ebb sets in. In a firth that is large compared with the

river falling into it, judging from results recently obtained

in the Firth of Forth,1 a state of equilibrium is arrived

at, the water increasing in salinity more and more gradu¬

ally as it proceeds seawards, the disturbing influence of the

tide becoming less and less, and the vertical distribution of

salinity more and more uniform until the river water meets

the sea, diffused through a nearly homogeneous mass with

a density little inferior to that of the ocean. Between the

extreme cases there are numerous gradations of estuary

depending on the ratio of river to sea inlet.

Deposits.—All seas within about 300 miles of continental

land, whatever may be their depth, are paved with terrige¬

nous debris, and all at a greater distance from shore are

carpeted with true pelagic deposits (see Pacific Ocean).

Marine Fauna and Flora.—The mixing of river with

sea water produces a marked difference in the fauna and

flora of seas. Where low salinity prevails diatoms abound,

probably on account of the greater amount of silica dis¬

solved in river water, and they form food for minute pelagic

animals and larvae, which are in turn preyed upon by larger

creatures. In some seas, such as the North Sea, there are

many celebrated fishing beds on the shallow banks of which

innumerable invertebrate animals live and form an inex¬

haustible food-supply for edible fishes. Naturalists have

remarked that in temperate seas enormous shoals of rela¬

tively few species are met with, while in tropical seas species

are very numerous and individuals comparatively few.

Organisms, such as the corals, which secrete carbonate of

lime appear to flourish more luxuriantly in warmer and

salter seas than in those which are colder and fresher.

The geological and dynamic aspects of seas are treated of

in Geology (vol. x. p. 284 sq.) and Geography (Physical) ;

and in Atlantic Ocean, Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Indian

Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, North Sea, Norwegian

Sea, Pacific Ocean, Polar Regions, and Red Sea the

general geographical and physical characters of oceans and

seas are described. In Meteorology some account is

given of the influence of the sea on climate, and chemical

problems connected with the ocean are discussed in Sea.

Water.

SEA-CAT. See Sea-Wolf, infra.

SEA-DEVIL. See Fishing-Frog, vol. ix. p. 269.

SEA-HORSE. Sea-horses {Hippocampina) are small

marine fishes which, together with pipe-fishes {Syn-

gnathina), form the order of Lophobranchiate fishes, as

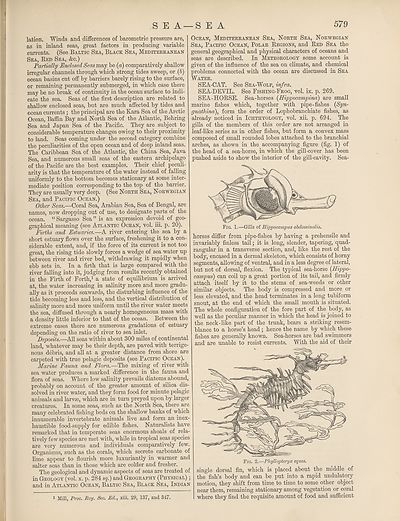

already noticed in Ichthyology, vol. xii. p. 694. The

gills of the members of this order are not arranged in

leaf-like series as in other fishes, but form a convex mass

composed of small rounded lobes attached to the branchial

arches, as shown in the accompanying figure (fig. 1) of

the head of a sea-horse, in which the gill-cover has been

pushed aside to show the interior of the gill-cavity. Sea-

Fig. 1.—Gills of Hippocampus abdominal is.

horses differ from pipe-fishes by having a prehensile and

invariably finless tail; it is long, slender, tapering, quad¬

rangular in a transverse section, and, like the rest of the

body, encased in a dermal skeleton, which consists of horny

segments, allowing of ventral, and in a less degree of lateral,

but not of dorsal, flexion. The typical sea-horse (Hippo¬

campus) can coil up a great portion of its tail, and firmly

attach itself by it to the stems of sea-weeds or other

similar objects. The body is compressed and more or

less elevated, and the head terminates in a long tubiform

snout, at the end of which the small mouth is situated.

The whole configuration of the fore part of the body, as

well as the peculiar manner in which the head is joined to

the neck-like part of the trunk, bears a striking resem¬

blance to a horse’s head; hence the name by which these

fishes are generally known. Sea-horses are bad swimmers

and are unable to resist currents. With the aid of their

single dorsal fin, which is placed about the middle of

the fish’s body and can be put into a rapid undulatory

motion, they shift from time to time to some other object

near them, remaining stationary among vegetation or coral

where they find the requisite amount of food and sufficient

1 Mill, Proc. Roy. Soc. Ed., xiii. 29, 137, and 347.

S E A —S E A

lation. Winds and differences of barometric pressure are,

as in inland seas, great factors in producing variable

currents. (See Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Mediterranean

Sea, Red Sea, &c.)

Partially Enclosed Seas may be (a) comparatively shallow

irregular channels through which strong tides sweep, or (b)

ocean basins cut off by barriers barely rising to the surface,

or remaining permanently submerged, in which case there

may be no break of continuity in the ocean surface to indi¬

cate the sea. Seas of the first description are related to

shallow enclosed seas, but are much affected by tides and

ocean currents; the principal are the Kara Sea of the Arctic

Ocean, Baffin Bay and North Sea of the Atlantic, Behring

Sea and Japan Sea of the Pacific. They are subject to

considerable temperature changes owing to their proximity

to land. Seas coming under the second category combine

the peculiarities of the open ocean and of deep inland seas.

The Caribbean Sea of the Atlantic, the China Sea, Java

Sea, and numerous small seas of the eastern archipelago

of the Pacific are the best examples. Their chief peculi¬

arity is that the temperature of the water instead of falling

uniformly to the bottom becomes stationary at some inter¬

mediate position corresponding to the top of the barrier.

They are usually very deep. (See North Sea, Norwegian

Sea, and Pacific Ocean.)

Other Seas.—Coral Sea, Arabian Sea, Sea of Bengal, are

names, now dropping out of use, to designate parts of the

ocean. “Sargasso Sea” is an expression devoid of geo¬

graphical meaning (see Atlantic Ocean, vol. iii. p. 20).

Firths and Estuaries.—A river entering the sea by a

short estuary flows over the surface, freshening it to a con¬

siderable extent, and, if the force of its current is not too

great, the rising tide slowly forces a wedge of sea water up

between river and river bed, withdrawing it rapidly when

ebb sets in. In a firth that is large compared with the

river falling into it, judging from results recently obtained

in the Firth of Forth,1 a state of equilibrium is arrived

at, the water increasing in salinity more and more gradu¬

ally as it proceeds seawards, the disturbing influence of the

tide becoming less and less, and the vertical distribution of

salinity more and more uniform until the river water meets

the sea, diffused through a nearly homogeneous mass with

a density little inferior to that of the ocean. Between the

extreme cases there are numerous gradations of estuary

depending on the ratio of river to sea inlet.

Deposits.—All seas within about 300 miles of continental

land, whatever may be their depth, are paved with terrige¬

nous debris, and all at a greater distance from shore are

carpeted with true pelagic deposits (see Pacific Ocean).

Marine Fauna and Flora.—The mixing of river with

sea water produces a marked difference in the fauna and

flora of seas. Where low salinity prevails diatoms abound,

probably on account of the greater amount of silica dis¬

solved in river water, and they form food for minute pelagic

animals and larvae, which are in turn preyed upon by larger

creatures. In some seas, such as the North Sea, there are

many celebrated fishing beds on the shallow banks of which

innumerable invertebrate animals live and form an inex¬

haustible food-supply for edible fishes. Naturalists have

remarked that in temperate seas enormous shoals of rela¬

tively few species are met with, while in tropical seas species

are very numerous and individuals comparatively few.

Organisms, such as the corals, which secrete carbonate of

lime appear to flourish more luxuriantly in warmer and

salter seas than in those which are colder and fresher.

The geological and dynamic aspects of seas are treated of

in Geology (vol. x. p. 284 sq.) and Geography (Physical) ;

and in Atlantic Ocean, Baltic Sea, Black Sea, Indian

Ocean, Mediterranean Sea, North Sea, Norwegian

Sea, Pacific Ocean, Polar Regions, and Red Sea the

general geographical and physical characters of oceans and

seas are described. In Meteorology some account is

given of the influence of the sea on climate, and chemical

problems connected with the ocean are discussed in Sea.

Water.

SEA-CAT. See Sea-Wolf, infra.

SEA-DEVIL. See Fishing-Frog, vol. ix. p. 269.

SEA-HORSE. Sea-horses {Hippocampina) are small

marine fishes which, together with pipe-fishes {Syn-

gnathina), form the order of Lophobranchiate fishes, as

already noticed in Ichthyology, vol. xii. p. 694. The

gills of the members of this order are not arranged in

leaf-like series as in other fishes, but form a convex mass

composed of small rounded lobes attached to the branchial

arches, as shown in the accompanying figure (fig. 1) of

the head of a sea-horse, in which the gill-cover has been

pushed aside to show the interior of the gill-cavity. Sea-

Fig. 1.—Gills of Hippocampus abdominal is.

horses differ from pipe-fishes by having a prehensile and

invariably finless tail; it is long, slender, tapering, quad¬

rangular in a transverse section, and, like the rest of the

body, encased in a dermal skeleton, which consists of horny

segments, allowing of ventral, and in a less degree of lateral,

but not of dorsal, flexion. The typical sea-horse (Hippo¬

campus) can coil up a great portion of its tail, and firmly

attach itself by it to the stems of sea-weeds or other

similar objects. The body is compressed and more or

less elevated, and the head terminates in a long tubiform

snout, at the end of which the small mouth is situated.

The whole configuration of the fore part of the body, as

well as the peculiar manner in which the head is joined to

the neck-like part of the trunk, bears a striking resem¬

blance to a horse’s head; hence the name by which these

fishes are generally known. Sea-horses are bad swimmers

and are unable to resist currents. With the aid of their

single dorsal fin, which is placed about the middle of

the fish’s body and can be put into a rapid undulatory

motion, they shift from time to time to some other object

near them, remaining stationary among vegetation or coral

where they find the requisite amount of food and sufficient

1 Mill, Proc. Roy. Soc. Ed., xiii. 29, 137, and 347.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (589) Page 579 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634936 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|