Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(575) Page 565

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

565

GERMAN.]

SCULPTURE

our-

.eentli

lentury.

tliat mannerism which grew so strong in Germany during

the 15th century. Of special beauty are the statuettes

which adorn the “beautiful fountain,” executed by Hein¬

rich der Balier (1385-1396), and richly decorated with gold

and colour by the painter Rudolf.1 A number of colossal

figures were executed for Cologne cathedral between 1349

and 1361, but they are of no great merit. Augsburg pro¬

duced several sculptors of ability about this time; the

museum possesses some very noble wooden statues of this

school, large in scale and dignified in treatment. On the

exterior of the choir of the church of Marienburg castle

is a very remarkable colossal figure of the Virgin of about

1340-50. Like the Hildesheim choir screen, it is made

of hard stucco and is decorated with glass mosaics. The

equestrian bronze group of St George and the Dragon

in the market-place at Prague is excellent in workmanship

and full of vigour, though

much wanting dignity of

style. Another fine work in

bronze of about the same date

is the effigy of Archbishop

Conrad (d. 1261) in Cologne

cathedral, executed many

years after his death. The

portrait appears truthful and

the whole figure is noble in

style. The military effigies

of this time in Germany as

elsewhere were almost un¬

avoidably stiff and lifeless

from the necessity of repre¬

senting them in plate ar¬

mour ; the ecclesiastical

chasuble, in which priestly

effigies nearly always ap¬

pear, is also a thoroughly

unsculpturesque form of

drapery, both from its awk¬

ward shape and its absence

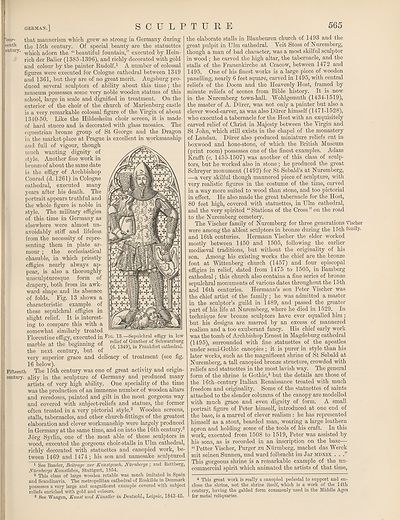

of folds. Pig. 13 shows a

characteristic example of

these sepulchral effigies in

slight relief. It is interest¬

ing to compare this with a

somewhat similarly treated

Florentine effigy, executed in Fm. 13.—Sepulchral effigy in low

, , , .i “V • relief of Gunther of Schwarzburg

marble at the begin 0 (cl. 1349), in Frankfort cathedral,

the next century, but ot

very superior grace and delicacy of treatment (see fig.

16 below).

Fifteenth The 15th century was one of great activity and origin-

century. ality in the sculpture of Germany and produced many

artists of very high ability. One speciality of the time

was the production of an immense number of wooden altars

and reredoses, painted and gilt in the most gorgeous way

and covered with subject-reliefs and statues, the former

often treated in a very pictorial style.2 Wooden screens,

stalls, tabernacles, and other church-fittings of the greatest

elaboration and clever workmanship were largely produced

in Germany at the same time, and on into the 16th century.3

Jorg Syrlin, one of the most able of these sculptors in

wood, executed the gorgeous choir-stalls in Ulm cathedral,

richly decorated with statuettes and canopied work, be¬

tween 1469 and 1474; his son and namesake sculptured

1 See Baader, Beitrage zur Kunstgesch. Numbergs ; and Rettberg,

Niirnbergs Kunstleben, Stuttgart, 1854.

2 This class of large wooden retable was much imitated in Spain

and Scandinavia. The metropolitan cathedral of Roskilde in Denmark

possesses a very large and magnificent example covered with subject

reliefs enriched with gold and colours.

3 See Waagen, Kunst und Kunstler in Deutschl., Leipsic, 1843-45.

the elaborate stalls in Blaubeuren church of 1493 and the

great pulpit in Ulm cathedral. Veit Stoss of Nuremberg,

though a man of bad character, was a most skilful sculptor

in wood ; he carved the high altar, the tabernacle, and the

stalls of the Frauenkirche at Cracow, between 1472 and

1495. One of his finest works is a large piece of wooden

panelling, nearly 6 feet square, carved in 1495, with central

reliefs of the Doom and the Heavenly Host, framed by

minute reliefs of scenes from Bible history. It is now

in the Nuremberg town-hall. Wohlgemuth (1434-1519),

the master of A. Diirer, was not only a painter but also a

clever wood-carver, as was also Diirer himself (1471-1528),

wTho executed a tabernacle for the Host with an exquisitely

carved relief of Christ in Majesty between the Virgin and

St John, which still exists in the chapel of the monastery

of Landau. Diirer also produced miniature reliefs cut in

boxwood and hone-stone, of which the British Museum

(print room) possesses one of the finest examples. Adam

Krafft (c. 1455-1507) was another of this class of sculp¬

tors, but he worked also in stone; he produced the great

Schreyer monument (1492) for St Sebald’s at Nuremberg,

—a very skilful though mannered piece of sculpture, with

very realistic figures in the costume of the time, carved

in a way more suited to wood than stone, and too pictorial

in effect. He also made the great tabernacle for the Host,

80 feet high, covered with statuettes, in Ulm cathedral,

and the very spirited “ Stations of the Cross ” on the road

to the Nuremberg cemetery.

The Vischer family of Nuremberg for three generations Vischer

were among the ablest sculptors in bronze during the 15th family,

and 16th centuries. Hermann Vischer the elder worked

mostly between 1450 and 1505, following the earlier

mediaeval traditions, but without the originality of his

son. Among his existing works the chief are the bronze

font at Wittenberg church (1457) and four episcopal

effigies in relief, dated from 1475 to 1505, in Bamberg

cathedral; this church also contains a fine series of bronze

sepulchral monuments of various dates throughout the 15th

and 16th centuries. Hermann’s son Peter Vischer was

the chief artist of the family; he was admitted a master

in the sculptor’s guild in 1489, and passed the greater

part of his life at Nuremberg, where he died in 1529. In

technique few bronze sculptors have ever equalled him;

but his designs are marred by an excess of mannered

realism and a too exuberant fancy. His chief early work

was the tomb of Archbishop Ernest in Magdeburg cathedral

(1495), surrounded with fine statuettes of the apostles

under semi-Gothic canopies; it is purer in style than his

later works, such as the magnificent shrine of St Sebald at

Nuremberg, a tall canopied bronze structure, crowded with

reliefs and statuettes in the most lavish way. The general

form of the shrine is Gothic,4 but the details are those of

the 16th-century Italian Renaissance treated with much

freedom and originality. Some of the statuettes of saints

attached to the slender columns of the canopy are modelled

with much grace and even dignity of form. A small

portrait figure of Peter himself, introduced at one end of

the base, is a marvel of clever realism : he has represented

himself as a stout, bearded man, wearing a large leathern

apron and holding some of the tools of his craft. In this

work, executed from 1508 to 1519, Peter was assisted by

his sons, as is recorded in an inscription on the base—

“ Petter Vischer, Purger zu Nurmberg, machet das Werck

mit seinen Sunnen, und ward folbracht im Jar mdxix . . .”

This gorgeous shrine is a remarkable example of the un¬

commercial spirit which animated the artists of that time,

4 This great work is really a canopied pedestal to support and en¬

close the shrine, not the shrine itself, which is a work of the 14th.

century, having the gabled form commonly used in the Middle Ages

for metal reliquaries.

GERMAN.]

SCULPTURE

our-

.eentli

lentury.

tliat mannerism which grew so strong in Germany during

the 15th century. Of special beauty are the statuettes

which adorn the “beautiful fountain,” executed by Hein¬

rich der Balier (1385-1396), and richly decorated with gold

and colour by the painter Rudolf.1 A number of colossal

figures were executed for Cologne cathedral between 1349

and 1361, but they are of no great merit. Augsburg pro¬

duced several sculptors of ability about this time; the

museum possesses some very noble wooden statues of this

school, large in scale and dignified in treatment. On the

exterior of the choir of the church of Marienburg castle

is a very remarkable colossal figure of the Virgin of about

1340-50. Like the Hildesheim choir screen, it is made

of hard stucco and is decorated with glass mosaics. The

equestrian bronze group of St George and the Dragon

in the market-place at Prague is excellent in workmanship

and full of vigour, though

much wanting dignity of

style. Another fine work in

bronze of about the same date

is the effigy of Archbishop

Conrad (d. 1261) in Cologne

cathedral, executed many

years after his death. The

portrait appears truthful and

the whole figure is noble in

style. The military effigies

of this time in Germany as

elsewhere were almost un¬

avoidably stiff and lifeless

from the necessity of repre¬

senting them in plate ar¬

mour ; the ecclesiastical

chasuble, in which priestly

effigies nearly always ap¬

pear, is also a thoroughly

unsculpturesque form of

drapery, both from its awk¬

ward shape and its absence

of folds. Pig. 13 shows a

characteristic example of

these sepulchral effigies in

slight relief. It is interest¬

ing to compare this with a

somewhat similarly treated

Florentine effigy, executed in Fm. 13.—Sepulchral effigy in low

, , , .i “V • relief of Gunther of Schwarzburg

marble at the begin 0 (cl. 1349), in Frankfort cathedral,

the next century, but ot

very superior grace and delicacy of treatment (see fig.

16 below).

Fifteenth The 15th century was one of great activity and origin-

century. ality in the sculpture of Germany and produced many

artists of very high ability. One speciality of the time

was the production of an immense number of wooden altars

and reredoses, painted and gilt in the most gorgeous way

and covered with subject-reliefs and statues, the former

often treated in a very pictorial style.2 Wooden screens,

stalls, tabernacles, and other church-fittings of the greatest

elaboration and clever workmanship were largely produced

in Germany at the same time, and on into the 16th century.3

Jorg Syrlin, one of the most able of these sculptors in

wood, executed the gorgeous choir-stalls in Ulm cathedral,

richly decorated with statuettes and canopied work, be¬

tween 1469 and 1474; his son and namesake sculptured

1 See Baader, Beitrage zur Kunstgesch. Numbergs ; and Rettberg,

Niirnbergs Kunstleben, Stuttgart, 1854.

2 This class of large wooden retable was much imitated in Spain

and Scandinavia. The metropolitan cathedral of Roskilde in Denmark

possesses a very large and magnificent example covered with subject

reliefs enriched with gold and colours.

3 See Waagen, Kunst und Kunstler in Deutschl., Leipsic, 1843-45.

the elaborate stalls in Blaubeuren church of 1493 and the

great pulpit in Ulm cathedral. Veit Stoss of Nuremberg,

though a man of bad character, was a most skilful sculptor

in wood ; he carved the high altar, the tabernacle, and the

stalls of the Frauenkirche at Cracow, between 1472 and

1495. One of his finest works is a large piece of wooden

panelling, nearly 6 feet square, carved in 1495, with central

reliefs of the Doom and the Heavenly Host, framed by

minute reliefs of scenes from Bible history. It is now

in the Nuremberg town-hall. Wohlgemuth (1434-1519),

the master of A. Diirer, was not only a painter but also a

clever wood-carver, as was also Diirer himself (1471-1528),

wTho executed a tabernacle for the Host with an exquisitely

carved relief of Christ in Majesty between the Virgin and

St John, which still exists in the chapel of the monastery

of Landau. Diirer also produced miniature reliefs cut in

boxwood and hone-stone, of which the British Museum

(print room) possesses one of the finest examples. Adam

Krafft (c. 1455-1507) was another of this class of sculp¬

tors, but he worked also in stone; he produced the great

Schreyer monument (1492) for St Sebald’s at Nuremberg,

—a very skilful though mannered piece of sculpture, with

very realistic figures in the costume of the time, carved

in a way more suited to wood than stone, and too pictorial

in effect. He also made the great tabernacle for the Host,

80 feet high, covered with statuettes, in Ulm cathedral,

and the very spirited “ Stations of the Cross ” on the road

to the Nuremberg cemetery.

The Vischer family of Nuremberg for three generations Vischer

were among the ablest sculptors in bronze during the 15th family,

and 16th centuries. Hermann Vischer the elder worked

mostly between 1450 and 1505, following the earlier

mediaeval traditions, but without the originality of his

son. Among his existing works the chief are the bronze

font at Wittenberg church (1457) and four episcopal

effigies in relief, dated from 1475 to 1505, in Bamberg

cathedral; this church also contains a fine series of bronze

sepulchral monuments of various dates throughout the 15th

and 16th centuries. Hermann’s son Peter Vischer was

the chief artist of the family; he was admitted a master

in the sculptor’s guild in 1489, and passed the greater

part of his life at Nuremberg, where he died in 1529. In

technique few bronze sculptors have ever equalled him;

but his designs are marred by an excess of mannered

realism and a too exuberant fancy. His chief early work

was the tomb of Archbishop Ernest in Magdeburg cathedral

(1495), surrounded with fine statuettes of the apostles

under semi-Gothic canopies; it is purer in style than his

later works, such as the magnificent shrine of St Sebald at

Nuremberg, a tall canopied bronze structure, crowded with

reliefs and statuettes in the most lavish way. The general

form of the shrine is Gothic,4 but the details are those of

the 16th-century Italian Renaissance treated with much

freedom and originality. Some of the statuettes of saints

attached to the slender columns of the canopy are modelled

with much grace and even dignity of form. A small

portrait figure of Peter himself, introduced at one end of

the base, is a marvel of clever realism : he has represented

himself as a stout, bearded man, wearing a large leathern

apron and holding some of the tools of his craft. In this

work, executed from 1508 to 1519, Peter was assisted by

his sons, as is recorded in an inscription on the base—

“ Petter Vischer, Purger zu Nurmberg, machet das Werck

mit seinen Sunnen, und ward folbracht im Jar mdxix . . .”

This gorgeous shrine is a remarkable example of the un¬

commercial spirit which animated the artists of that time,

4 This great work is really a canopied pedestal to support and en¬

close the shrine, not the shrine itself, which is a work of the 14th.

century, having the gabled form commonly used in the Middle Ages

for metal reliquaries.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (575) Page 565 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634754 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|