Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(571) Page 561

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

561

ENGLISH.]

SCULPTURE

they are unfortunately much injured by the use of a thicker

outline on one side of the figures,-—an unsuccessful attempt

to give a suggestion of shadow. Flaxman’s best pupil was

Baily (1788-1867), chiefly celebrated for his nude marble

figure of Eve.

line- During the first half of the 19th century the preva-

eenth lence of a cold lifeless pseudo-classic style was fatal to

entury. individual talent, and robbed the sculpture of England of

all real vigour and spirit. Francis Chantrey (1782-1841)

produced a great quantity of sculpture, especially sepulchral

monuments, which were much admired in spite of their

very limited merits. Allan Cunningham and Henry Weekes

worked in some cases in conjunction with Chantrey, who

was not wanting in technical skill, as is shown by his

clever marble relief of two dead woodcocks. John Gibson

(1790-1866) was perhaps after Flaxman the most success¬

ful of the English classic school, and produced some works

of real merit. He strove eagerly to revive the poly¬

chromatic decoration of sculpture in imitation of the cir-

cumlitio of classical times. His Venus Victrix, shown at

the exhibition in London of 1862 (a work of about six

years earlier), was the first of his coloured statues which

attracted much attention. The prejudice, however, in

favour of white marble was too strong, and both the

popular verdict and that of other sculptors were strongly

adverse to the “ tinted Venus.” The fact was that Gibson’s

colouring was timidly applied : it was a sort of compromise

between the two systems, and thus his sculpture lost the

special qualities of a pure marble surface, without gaining

the richly decorative effect of the polychromy either of the

Greeks or of the mediaeval period.1 The other chief sculp¬

tors of the same very inartistic period were Banks, the

elder Westmacott (who modelled the Achilles in Hyde Park),

R. Wyatt (who cast the equestrian statue of Wellington,

lately removed from London), Macdowell, Campbell, Mar¬

shall, and Bell.

During the last hundred years a large number of hono¬

rary statues have been set up in the Houses of Parliament,

Westminster Hall and Abbey, and in other public places. in

London. Most of these, though modelled as a rule with

some scholastic accuracy, are quite dull and spiritless,

and, whilst free from the violently bad taste of such men

as Bernini or Roubiliac, they lack the force and vigorous

originality which go far to redeem what is offensive in the

sculpture of the 17 th and 18th centuries. The modern

public statues of London and elsewhere are as a rule

tamely respectable and quite uninteresting. One brilliant

exception is the Wellington monument in St Paul’s Cathe¬

dral, probably the finest plastic work of modern times. It

Stevens, was the work of Alfred Stevens (1817-1875), a sculptor of

the highest talent, who lived and died almost unrecognized

by the British public. The commission for this monu¬

ment was given to Stevens after a public competition; and

he agreed to carry it out for <£20,000,—a quite inadequate

sum, as it afterwards turned out. The greater part of his

life Stevens devoted to this grand monument, constantly

harassed and finally worn out by the interference_ of

Government, want of money, and other difficulties.

Though he completed the model, Stevens did not live to

see the monument set up,—perhaps fortunately for him,

as it has been placed in a small side chapel, where the

effect of the whole is utterly destroyed, and its magnificent

bronze groups hidden from view. The monument consists

of a sarcophagus supporting a recumbent bronze effigy of

the duke, over which is an arched marble canopy of late

Renaissance style on delicately enriched shafts. At each

1 Gibson bequeathed his fortune and the models of his chief works

to the Royal Academy, where the latter are now crowded in an upper

room adjoining the Diploma Gallery. See Lady Eastlake, Life of

Gibson, London, 1870.

end of the upper part of the canopy is a large bronze group,

one representing Truth tearing the tongue out of the mouth

of Falsehood, and the other Valour trampling Cowardice

under foot (see fig. 8). The two virtues are represented

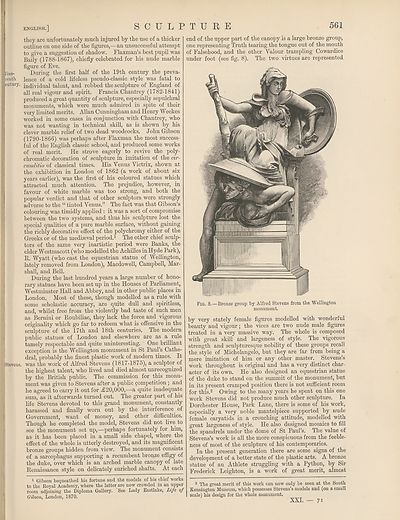

Fig. 8.—Bronze group by Alfred Stevens from the Wellington

monument.

by very stately female figures modelled with wonderful

beauty and vigour; the vices are two nude male figures

treated in a very massive way. The whole is composed

with great skill and largeness of style. The vigorous

strength and sculpturesque nobility of these groups recall

the style of Michelangelo, but they are far from being a

mere imitation of him or any other master. Stevens’s

work throughout is original and has a very distinct char¬

acter of its own. He also designed an equestrian statue

of the duke to stand on the summit of the monument, but

in its present cramped position there is not sufficient room

for this.2 Owing to the many years he spent on this one

work Stevens did not produce much other sculpture. In

Dorchester House, Park Lane, there is some of his work,

especially a very noble mantelpiece supported by nude

female caryatids in a crouching attitude, modelled with

great largeness of style. He also designed mosaics to fill

the spandrels under the dome of St Paul’s. The value of

Stevens’s work is all the more conspicuous from the feeble¬

ness of most of the sculpture of his contemporaries.

In the present generation there are some signs of the

development of a better state of the plastic arts. A bronze

statue of an Athlete struggling with a Python, by Sir

Frederick Leighton, is a work of great merit, almost

2 The great merit of this work can now only be seen at the South

Kensington Museum, which possesses Stevens’s models and (on a small

scale) his design for the whole monument.

XXL — 71

ENGLISH.]

SCULPTURE

they are unfortunately much injured by the use of a thicker

outline on one side of the figures,-—an unsuccessful attempt

to give a suggestion of shadow. Flaxman’s best pupil was

Baily (1788-1867), chiefly celebrated for his nude marble

figure of Eve.

line- During the first half of the 19th century the preva-

eenth lence of a cold lifeless pseudo-classic style was fatal to

entury. individual talent, and robbed the sculpture of England of

all real vigour and spirit. Francis Chantrey (1782-1841)

produced a great quantity of sculpture, especially sepulchral

monuments, which were much admired in spite of their

very limited merits. Allan Cunningham and Henry Weekes

worked in some cases in conjunction with Chantrey, who

was not wanting in technical skill, as is shown by his

clever marble relief of two dead woodcocks. John Gibson

(1790-1866) was perhaps after Flaxman the most success¬

ful of the English classic school, and produced some works

of real merit. He strove eagerly to revive the poly¬

chromatic decoration of sculpture in imitation of the cir-

cumlitio of classical times. His Venus Victrix, shown at

the exhibition in London of 1862 (a work of about six

years earlier), was the first of his coloured statues which

attracted much attention. The prejudice, however, in

favour of white marble was too strong, and both the

popular verdict and that of other sculptors were strongly

adverse to the “ tinted Venus.” The fact was that Gibson’s

colouring was timidly applied : it was a sort of compromise

between the two systems, and thus his sculpture lost the

special qualities of a pure marble surface, without gaining

the richly decorative effect of the polychromy either of the

Greeks or of the mediaeval period.1 The other chief sculp¬

tors of the same very inartistic period were Banks, the

elder Westmacott (who modelled the Achilles in Hyde Park),

R. Wyatt (who cast the equestrian statue of Wellington,

lately removed from London), Macdowell, Campbell, Mar¬

shall, and Bell.

During the last hundred years a large number of hono¬

rary statues have been set up in the Houses of Parliament,

Westminster Hall and Abbey, and in other public places. in

London. Most of these, though modelled as a rule with

some scholastic accuracy, are quite dull and spiritless,

and, whilst free from the violently bad taste of such men

as Bernini or Roubiliac, they lack the force and vigorous

originality which go far to redeem what is offensive in the

sculpture of the 17 th and 18th centuries. The modern

public statues of London and elsewhere are as a rule

tamely respectable and quite uninteresting. One brilliant

exception is the Wellington monument in St Paul’s Cathe¬

dral, probably the finest plastic work of modern times. It

Stevens, was the work of Alfred Stevens (1817-1875), a sculptor of

the highest talent, who lived and died almost unrecognized

by the British public. The commission for this monu¬

ment was given to Stevens after a public competition; and

he agreed to carry it out for <£20,000,—a quite inadequate

sum, as it afterwards turned out. The greater part of his

life Stevens devoted to this grand monument, constantly

harassed and finally worn out by the interference_ of

Government, want of money, and other difficulties.

Though he completed the model, Stevens did not live to

see the monument set up,—perhaps fortunately for him,

as it has been placed in a small side chapel, where the

effect of the whole is utterly destroyed, and its magnificent

bronze groups hidden from view. The monument consists

of a sarcophagus supporting a recumbent bronze effigy of

the duke, over which is an arched marble canopy of late

Renaissance style on delicately enriched shafts. At each

1 Gibson bequeathed his fortune and the models of his chief works

to the Royal Academy, where the latter are now crowded in an upper

room adjoining the Diploma Gallery. See Lady Eastlake, Life of

Gibson, London, 1870.

end of the upper part of the canopy is a large bronze group,

one representing Truth tearing the tongue out of the mouth

of Falsehood, and the other Valour trampling Cowardice

under foot (see fig. 8). The two virtues are represented

Fig. 8.—Bronze group by Alfred Stevens from the Wellington

monument.

by very stately female figures modelled with wonderful

beauty and vigour; the vices are two nude male figures

treated in a very massive way. The whole is composed

with great skill and largeness of style. The vigorous

strength and sculpturesque nobility of these groups recall

the style of Michelangelo, but they are far from being a

mere imitation of him or any other master. Stevens’s

work throughout is original and has a very distinct char¬

acter of its own. He also designed an equestrian statue

of the duke to stand on the summit of the monument, but

in its present cramped position there is not sufficient room

for this.2 Owing to the many years he spent on this one

work Stevens did not produce much other sculpture. In

Dorchester House, Park Lane, there is some of his work,

especially a very noble mantelpiece supported by nude

female caryatids in a crouching attitude, modelled with

great largeness of style. He also designed mosaics to fill

the spandrels under the dome of St Paul’s. The value of

Stevens’s work is all the more conspicuous from the feeble¬

ness of most of the sculpture of his contemporaries.

In the present generation there are some signs of the

development of a better state of the plastic arts. A bronze

statue of an Athlete struggling with a Python, by Sir

Frederick Leighton, is a work of great merit, almost

2 The great merit of this work can now only be seen at the South

Kensington Museum, which possesses Stevens’s models and (on a small

scale) his design for the whole monument.

XXL — 71

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (571) Page 561 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634702 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|