Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(566) Page 556 - Sculpture

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

556

Early

Chris¬

tian.

SCULPTUEE

THE present article is confined to tlie sculpture of the

Middle Ages and modern times; classical sculpture

has been already treated of under Arch/eology (Class¬

ical), vol. ii. p. 343 sq., and in the articles on the several

individual artists.

In the 4th century a.d., under the rule of Constantine’s

successors, the plastic arts in the Roman world reached

the lowest point of degradation to which they ever fell.

Coarse in workmanship, intensely feeble in design, and

utterly without expression or life, the pagan sculpture of

that time is merely a dull and ignorant imitation of the

work of previous centuries. The old faith was dead, and

the art which had sprung

from it died with it. In

the same century a large ' ^

amount of sculpture was

produced by Christian

workmen, which, though

it reached no very high

standard of merit, was at

least far superior to the

pagan work. Although

it shows no increase of

technical skill or know¬

ledge of the human form,

yet the mere fact that it

was inspired and its sub¬

jects supplied by a real

living faith was quite

sufficient to give it a

vigour and a dramatic

force which raise it aes¬

thetically far above the

expiring efforts of pagan¬

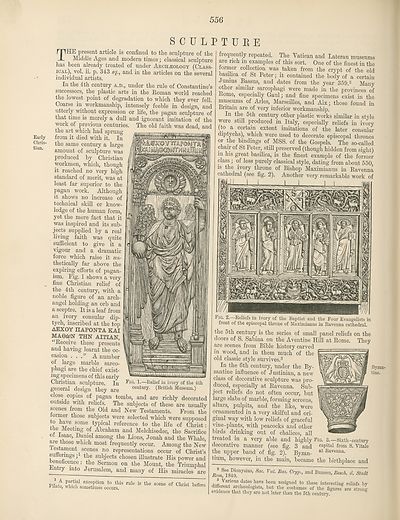

ism. Fig. 1 shows a very

fine Christian relief of

the 4th century, with a

noble figure of an arch¬

angel holding an orb and

a sceptre. It is a leaf from

an ivory consular dip¬

tych, inscribed at the top

AEXOY HAPONTA KAI

MA0^N THN AITIAN,

“Receive these presents

and having learnt the oc¬

casion ...” A number

of large marble sarco¬

phagi are the chief exist¬

ing specimens of this early

Christian sculpture. In

general design they are

Fig. 1.—Relief in ivory of the 4th

century. (British Museum.)

close copies of pagan tombs, and are richly decorated

outside with reliefs. The subjects of these are usually

scenes from the Old and Hew Testaments. From the

tormer those subjects were selected which were supposed

to have some typical reference to the life of Christ •

the Meeting of Abraham and Melchisedec, the Sacrifice

0 1®aac’ Daniel among the Lions, Jonah and the Whale,

are those which most frequently occur. Among the Hew

estament scenes no representations occur of Christ’s

sufferings; the subjects chosen illustrate His power and

beneficence : the Sermon on the Mount, the Triumphal

Jintry into Jerusalem, and many of His miracles are

Pilltf ™ exc®Ption to tllis is the scene of Christ before

Pilate, which sometimes occurs. e

frequently repeated. The Vatican and Lateran museums

are rich m examples of this sort. One of the finest in the

former collection was taken from the crypt of the old

basilica of St Peter; it contained the body of a certain

Junius Bassus, and dates from the year 359.2 Many

other similar sarcophagi were made in the provinces of

Rome, especially Gaul; and fine specimens exist in the

museums of Arles, _ Marseilles, and Aix; those found in

Britain are of very inferior workmanship.

In the 5th century other plastic works similar in style

were still produced in Italy, especially reliefs in ivory

(to a certain extent imitations of the later consular

diptychs), which were used to decorate episcopal thrones

or the bindings of MSS. of the Gospels. The so-called

chair of St Peter, still preserved (though hidden from sight)

in liis gieat basilica, is the finest example of the former

class; of less purely classical style, dating from about 550,

is the ivory throne of Bishop Maximianus in Ravenna

cathedral (see fig. 2). Another very remarkable work of

Fig. 2.—Reliefs in ivory of the Baptist and the Four Evangelists in

front of the episcopal throne of Maximianus in Ravenna cathedral.

the 5th century is the series of small panel reliefs on the

doors of S. Sabina on the Aventine Hill at Rome. They

are scenes from Bible history carved

in wood, and in them much of the

old classic style survives.3

In the 6th century, under the By- \ [ Byzan-

zantine influence of Justinian, a new tine-

class of decorative sculpture was pro¬

duced, especially at Ravenna. Sub¬

ject reliefs do not often occur, but

large slabs of marble, forming screens,

altars, pulpits, and the like, were

ornamented in a very skilful and ori¬

ginal way with low reliefs of graceful

vine-plants, with peacocks and other

birds drinking out of chalices, all

treated in a very able and highly Fig. 3.—Sixth-century

decorative manner (see fig. 3 and capital from S. Vitale

the upper band of fig. 2). Byzan- at Kaveuua-

tium, however, in the main, became the birthplace and

xlXT78™’ ^ YaL BaS' CV^'’ and Bunsen> Besch. d. Stadt

* Va]"10us dates have been assigned to these interesting reliefs by

different archaeologists, but the costumes of the figures are strong

evidence that they are not later than the 5th century.

Early

Chris¬

tian.

SCULPTUEE

THE present article is confined to tlie sculpture of the

Middle Ages and modern times; classical sculpture

has been already treated of under Arch/eology (Class¬

ical), vol. ii. p. 343 sq., and in the articles on the several

individual artists.

In the 4th century a.d., under the rule of Constantine’s

successors, the plastic arts in the Roman world reached

the lowest point of degradation to which they ever fell.

Coarse in workmanship, intensely feeble in design, and

utterly without expression or life, the pagan sculpture of

that time is merely a dull and ignorant imitation of the

work of previous centuries. The old faith was dead, and

the art which had sprung

from it died with it. In

the same century a large ' ^

amount of sculpture was

produced by Christian

workmen, which, though

it reached no very high

standard of merit, was at

least far superior to the

pagan work. Although

it shows no increase of

technical skill or know¬

ledge of the human form,

yet the mere fact that it

was inspired and its sub¬

jects supplied by a real

living faith was quite

sufficient to give it a

vigour and a dramatic

force which raise it aes¬

thetically far above the

expiring efforts of pagan¬

ism. Fig. 1 shows a very

fine Christian relief of

the 4th century, with a

noble figure of an arch¬

angel holding an orb and

a sceptre. It is a leaf from

an ivory consular dip¬

tych, inscribed at the top

AEXOY HAPONTA KAI

MA0^N THN AITIAN,

“Receive these presents

and having learnt the oc¬

casion ...” A number

of large marble sarco¬

phagi are the chief exist¬

ing specimens of this early

Christian sculpture. In

general design they are

Fig. 1.—Relief in ivory of the 4th

century. (British Museum.)

close copies of pagan tombs, and are richly decorated

outside with reliefs. The subjects of these are usually

scenes from the Old and Hew Testaments. From the

tormer those subjects were selected which were supposed

to have some typical reference to the life of Christ •

the Meeting of Abraham and Melchisedec, the Sacrifice

0 1®aac’ Daniel among the Lions, Jonah and the Whale,

are those which most frequently occur. Among the Hew

estament scenes no representations occur of Christ’s

sufferings; the subjects chosen illustrate His power and

beneficence : the Sermon on the Mount, the Triumphal

Jintry into Jerusalem, and many of His miracles are

Pilltf ™ exc®Ption to tllis is the scene of Christ before

Pilate, which sometimes occurs. e

frequently repeated. The Vatican and Lateran museums

are rich m examples of this sort. One of the finest in the

former collection was taken from the crypt of the old

basilica of St Peter; it contained the body of a certain

Junius Bassus, and dates from the year 359.2 Many

other similar sarcophagi were made in the provinces of

Rome, especially Gaul; and fine specimens exist in the

museums of Arles, _ Marseilles, and Aix; those found in

Britain are of very inferior workmanship.

In the 5th century other plastic works similar in style

were still produced in Italy, especially reliefs in ivory

(to a certain extent imitations of the later consular

diptychs), which were used to decorate episcopal thrones

or the bindings of MSS. of the Gospels. The so-called

chair of St Peter, still preserved (though hidden from sight)

in liis gieat basilica, is the finest example of the former

class; of less purely classical style, dating from about 550,

is the ivory throne of Bishop Maximianus in Ravenna

cathedral (see fig. 2). Another very remarkable work of

Fig. 2.—Reliefs in ivory of the Baptist and the Four Evangelists in

front of the episcopal throne of Maximianus in Ravenna cathedral.

the 5th century is the series of small panel reliefs on the

doors of S. Sabina on the Aventine Hill at Rome. They

are scenes from Bible history carved

in wood, and in them much of the

old classic style survives.3

In the 6th century, under the By- \ [ Byzan-

zantine influence of Justinian, a new tine-

class of decorative sculpture was pro¬

duced, especially at Ravenna. Sub¬

ject reliefs do not often occur, but

large slabs of marble, forming screens,

altars, pulpits, and the like, were

ornamented in a very skilful and ori¬

ginal way with low reliefs of graceful

vine-plants, with peacocks and other

birds drinking out of chalices, all

treated in a very able and highly Fig. 3.—Sixth-century

decorative manner (see fig. 3 and capital from S. Vitale

the upper band of fig. 2). Byzan- at Kaveuua-

tium, however, in the main, became the birthplace and

xlXT78™’ ^ YaL BaS' CV^'’ and Bunsen> Besch. d. Stadt

* Va]"10us dates have been assigned to these interesting reliefs by

different archaeologists, but the costumes of the figures are strong

evidence that they are not later than the 5th century.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (566) Page 556 - Sculpture |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634637 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|