Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(563) Page 553

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

S C R—S C R

553

gratings for optical purposes. Suppose it is our purpose to produce

a screw which is finally to be 9 inches long, not including bearings,

and 1| inches in diameter. Select a bar of soft Bessemer steel,

which has not the hard spots usually found in cast steel, about 1|

inches in diameter and 30 long. Put it between lathe centres and

turn it down to 1 inch diameter everywhere, except about 12 inches

in the centre, where it is left a little over 11 inches in diameter for

cutting the screw. Now cut the screw with a triangular thread a

little sharper than 60°. Above all, avoid a fine screw, using about

20 threads to the inch.

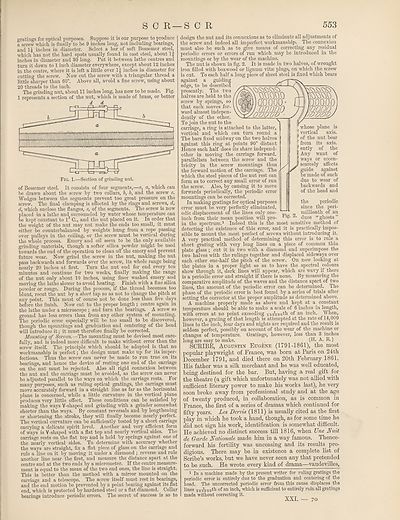

The grinding nut, about 11 inches long, has now to be made. Fig.

1 represents a section of the nut, which is made of brass, or better

of Bessemer steel. It consists of four segments,—a, a, which can

be drawn about the screw by two collars, b, b, and the screw c.

Wedges between the segments prevent too great pressure on the

screw. The final clamping is effected by the rings and screws, d,

d, which enclose the flanges, e, of the segments. The screw is now

placed in a lathe and. surrounded by water whose temperature can

be kept constant to 1° C., and the nut placed on it. In order that

the weight of the nut may not make the ends too small, it must

either be counterbalanced by weights hung from a rope passing

over pulleys in the ceiling, or the screw must be vertical during

the whole process. Emery and oil seem to be the only available

grinding materials, though a softer silica powder might be used

towards the end of the operation to clean off the emery and prevent

future wear. Now grind the screw in the nut, making the nut

pass backwards and forwards over the screw, its whole range being

nearly 20 inches at first. Turn the nut end for end every ten

minutes and continue for two weeks, finally making the range

of the nut only about 10 inches, using finer washed emery and

moving the lathe slower to avoid heating. Finish with a fine silica

powder or rouge. During the process, if the thread becomes too

blunt, recut the nut by a short tap so as not to change the pitch at

any point. This must of course not be done less than five days

before the finish. Now cut to the proper length; centre again in

the lathe under a microscope ; and turn the bearings. A screw so

ground has less errors than from any other system of mounting.

The periodic error especially will be too small to be discovered,

though the mountings and graduation and centering of the head

will introduce* it; it must therefore finally be corrected.

Mounting of Screws.—The mounting must be devised most care¬

fully, and is indeed more difficult to make without error than the

screw itself. The principle which should be adopted is that no

workmanship is perfect; the design must make up for its imper¬

fections. Thus the screw can never be made to run true on its

bearings, and hence the device of resting one end of the carriage

on the nut must be rejected. Also all rigid connexion between

the nut and the carriage must be avoided, as the screw can never

be adjusted parallel to the ways on which the carriage rests. For

many purposes, such as ruling optical gratings, the carriage must

move accurately forward in a straight line as far as the horizontal

plane is concerned, while a little curvature in the vertical plane

produces very little effect. These conditions can be satisfied by

making the ways V-shaped and grinding with a grinder somewhat

shorter than the ways. By constant reversals and by lengthening

or shortening the stroke, they will finally become nearly perfect.

The vertical curvature can be sufficiently tested by a short carriage

carrying a delicate spirit level. Another and very efficient form

of ways is V-shaped with a flat top and nearly vertical sides. The

carriage rests on the flat top and is held by springs against one of

the nearly vertical sides. To determine with accuracy whether

the ways are straight, fix a flat piece of glass on the carriage and

rule a line on it by moving it under a diamond ; reverse and rule

another line near the first, and measure the distance apart at the

centre and at the two ends by a micrometer. If the centre measure¬

ment is equal to the mean of the two end ones, the line is straight.

This is better than the method with a mirror mounted on the

carriage and a telescope. The screw itself must rest in bearings,

and the end motion be prevented by a point bearing against its flat

end, which is protected by hardened steel or a flat diamond.. Collar

bearings introduce periodic errors. The secret of success is so to

design the nut and its connexions as to eliminate all adjustments of

the screw and indeed all imperfect workmanship. The connexion

must also he such as to give means of correcting any residual

periodic errors or errors of run which may be introduced in the

mountings or by the wear of the machine.

The nut is shown in fig. 2. It is made in two halves, of wrought

iron filled with boxwood or lignum vitse plugs, on which the screw

is cut. To each half a long piece of sheet steel is fixed which bears

against a guiding

edge, to be described

presently. The two

halves are held to the

screw by springs, so

that each moves for¬

ward almost indepen¬

dently of the other.

To join the nut to the

carriage, a ring is attached to the latter,

vertical and which can turn round a

The bars fixed midway on the two halves

against this ring at points 90° distant

Hence each half does its share independ-

other in moving the carriage forward,

parallelism between the screw and the

tricity in the screw mountings thus

the forward motion of the carriage. The

which the steel pieces of the nut rest can

form as to correct any small error of run

the screw. Also, by causing it to move

forwards periodically, the periodic error

mountings can be corrected.

In making gratings for optical purposes

error must be very perfectly eliminated,

odic displacement of the lines only one-

inch from their mean position will pro¬

in the spectrum.1

If

whose plane is

vertical axis,

of the nut bear

from its axis,

ently of the

Any want of

ways or eccen-

scarcely affects

guide against

be made of such

due to wear of

backwards and

of the head and

the periodic

since the peri-

millionth of an

Fig. 2. (]uce «ghosts ”

__ ^ Indeed this is the most sensitive method of

detecting the existence of this error, and it is practically impos¬

sible to mount the most perfect of screws without introducing it.

A very practical method of determining this error is to rule a

short grating with very long lines on a piece of common thin

plate glass ; cut it in two with a diamond and superimpose the

two halves with the rulings together and displaced sideways over-

each other one-half the pitch of the screw. On now looking at

the plates in a proper light so as to have the spectral colours

show through it, dark lines will appear, which are wavy if there

is a periodic error and straight if there is none. By measuring the

comparative amplitude of the waves and the distance apart of two

lines, the amount of the periodic error can be determined. The

phase of the periodic error is best found by a series of trials after-

setting the corrector at the proper amplitude as determined above.

A machine properly made as above and kept at a. constant

temperature should be able to make a scale of 6 inches in length,

with errors at no point exceeding xr>rnnntih of an inch. AVhen,

however, a grating of that length is attempted at the rate of 14,000

lines to the inch, four days and nights are required and the result is

seldom perfect, possibly on account of the wear of the machine or

changes of temperature. Gratings, however, less than 3 inches

long are easy to make. (H. A. R.)

SCRIBE, Augustin Eugene (1791-1861), the most

popular playwright of France, was born at Paris on 24th

December 1791, and died there on 20th February 1861.

His father was a silk merchant and he was well educated,

being destined for the bar. But, having a real gift for

the theatre (a gift which unfortunately was not allied with

sufficient literary power to make his works last), he very

soon broke away from professional study and at the age

of twenty produced, in collaboration, as is common in

France, the first of a series of dramas which continued for

fifty years. Les Dervis (1811) is usually cited as the first

play in which he took a hand, though, as for some time he

did not sign his work, identification is somewhat difficult.

He achieved no distinct success till 1816, when Une Nuit

de Garde Nationale made him in a way famous. Thence¬

forward his fertility was unceasing and its results pro¬

digious. There may be in existence a complete list of

Scribe’s works, but we have never seen any that pretended

to be such. He wrote every kind of drama—vaudevilles,

1 In a machine made by the present writer for ruling gratings the

periodic error is entirely due to the graduation and centering of the

head. The uncorrected periodic error from this cause displaces the

lines Annrth of an inch, which is sufficient to entirely ruin all gratings

made without correcting it.

XXL — 70

553

gratings for optical purposes. Suppose it is our purpose to produce

a screw which is finally to be 9 inches long, not including bearings,

and 1| inches in diameter. Select a bar of soft Bessemer steel,

which has not the hard spots usually found in cast steel, about 1|

inches in diameter and 30 long. Put it between lathe centres and

turn it down to 1 inch diameter everywhere, except about 12 inches

in the centre, where it is left a little over 11 inches in diameter for

cutting the screw. Now cut the screw with a triangular thread a

little sharper than 60°. Above all, avoid a fine screw, using about

20 threads to the inch.

The grinding nut, about 11 inches long, has now to be made. Fig.

1 represents a section of the nut, which is made of brass, or better

of Bessemer steel. It consists of four segments,—a, a, which can

be drawn about the screw by two collars, b, b, and the screw c.

Wedges between the segments prevent too great pressure on the

screw. The final clamping is effected by the rings and screws, d,

d, which enclose the flanges, e, of the segments. The screw is now

placed in a lathe and. surrounded by water whose temperature can

be kept constant to 1° C., and the nut placed on it. In order that

the weight of the nut may not make the ends too small, it must

either be counterbalanced by weights hung from a rope passing

over pulleys in the ceiling, or the screw must be vertical during

the whole process. Emery and oil seem to be the only available

grinding materials, though a softer silica powder might be used

towards the end of the operation to clean off the emery and prevent

future wear. Now grind the screw in the nut, making the nut

pass backwards and forwards over the screw, its whole range being

nearly 20 inches at first. Turn the nut end for end every ten

minutes and continue for two weeks, finally making the range

of the nut only about 10 inches, using finer washed emery and

moving the lathe slower to avoid heating. Finish with a fine silica

powder or rouge. During the process, if the thread becomes too

blunt, recut the nut by a short tap so as not to change the pitch at

any point. This must of course not be done less than five days

before the finish. Now cut to the proper length; centre again in

the lathe under a microscope ; and turn the bearings. A screw so

ground has less errors than from any other system of mounting.

The periodic error especially will be too small to be discovered,

though the mountings and graduation and centering of the head

will introduce* it; it must therefore finally be corrected.

Mounting of Screws.—The mounting must be devised most care¬

fully, and is indeed more difficult to make without error than the

screw itself. The principle which should be adopted is that no

workmanship is perfect; the design must make up for its imper¬

fections. Thus the screw can never be made to run true on its

bearings, and hence the device of resting one end of the carriage

on the nut must be rejected. Also all rigid connexion between

the nut and the carriage must be avoided, as the screw can never

be adjusted parallel to the ways on which the carriage rests. For

many purposes, such as ruling optical gratings, the carriage must

move accurately forward in a straight line as far as the horizontal

plane is concerned, while a little curvature in the vertical plane

produces very little effect. These conditions can be satisfied by

making the ways V-shaped and grinding with a grinder somewhat

shorter than the ways. By constant reversals and by lengthening

or shortening the stroke, they will finally become nearly perfect.

The vertical curvature can be sufficiently tested by a short carriage

carrying a delicate spirit level. Another and very efficient form

of ways is V-shaped with a flat top and nearly vertical sides. The

carriage rests on the flat top and is held by springs against one of

the nearly vertical sides. To determine with accuracy whether

the ways are straight, fix a flat piece of glass on the carriage and

rule a line on it by moving it under a diamond ; reverse and rule

another line near the first, and measure the distance apart at the

centre and at the two ends by a micrometer. If the centre measure¬

ment is equal to the mean of the two end ones, the line is straight.

This is better than the method with a mirror mounted on the

carriage and a telescope. The screw itself must rest in bearings,

and the end motion be prevented by a point bearing against its flat

end, which is protected by hardened steel or a flat diamond.. Collar

bearings introduce periodic errors. The secret of success is so to

design the nut and its connexions as to eliminate all adjustments of

the screw and indeed all imperfect workmanship. The connexion

must also he such as to give means of correcting any residual

periodic errors or errors of run which may be introduced in the

mountings or by the wear of the machine.

The nut is shown in fig. 2. It is made in two halves, of wrought

iron filled with boxwood or lignum vitse plugs, on which the screw

is cut. To each half a long piece of sheet steel is fixed which bears

against a guiding

edge, to be described

presently. The two

halves are held to the

screw by springs, so

that each moves for¬

ward almost indepen¬

dently of the other.

To join the nut to the

carriage, a ring is attached to the latter,

vertical and which can turn round a

The bars fixed midway on the two halves

against this ring at points 90° distant

Hence each half does its share independ-

other in moving the carriage forward,

parallelism between the screw and the

tricity in the screw mountings thus

the forward motion of the carriage. The

which the steel pieces of the nut rest can

form as to correct any small error of run

the screw. Also, by causing it to move

forwards periodically, the periodic error

mountings can be corrected.

In making gratings for optical purposes

error must be very perfectly eliminated,

odic displacement of the lines only one-

inch from their mean position will pro¬

in the spectrum.1

If

whose plane is

vertical axis,

of the nut bear

from its axis,

ently of the

Any want of

ways or eccen-

scarcely affects

guide against

be made of such

due to wear of

backwards and

of the head and

the periodic

since the peri-

millionth of an

Fig. 2. (]uce «ghosts ”

__ ^ Indeed this is the most sensitive method of

detecting the existence of this error, and it is practically impos¬

sible to mount the most perfect of screws without introducing it.

A very practical method of determining this error is to rule a

short grating with very long lines on a piece of common thin

plate glass ; cut it in two with a diamond and superimpose the

two halves with the rulings together and displaced sideways over-

each other one-half the pitch of the screw. On now looking at

the plates in a proper light so as to have the spectral colours

show through it, dark lines will appear, which are wavy if there

is a periodic error and straight if there is none. By measuring the

comparative amplitude of the waves and the distance apart of two

lines, the amount of the periodic error can be determined. The

phase of the periodic error is best found by a series of trials after-

setting the corrector at the proper amplitude as determined above.

A machine properly made as above and kept at a. constant

temperature should be able to make a scale of 6 inches in length,

with errors at no point exceeding xr>rnnntih of an inch. AVhen,

however, a grating of that length is attempted at the rate of 14,000

lines to the inch, four days and nights are required and the result is

seldom perfect, possibly on account of the wear of the machine or

changes of temperature. Gratings, however, less than 3 inches

long are easy to make. (H. A. R.)

SCRIBE, Augustin Eugene (1791-1861), the most

popular playwright of France, was born at Paris on 24th

December 1791, and died there on 20th February 1861.

His father was a silk merchant and he was well educated,

being destined for the bar. But, having a real gift for

the theatre (a gift which unfortunately was not allied with

sufficient literary power to make his works last), he very

soon broke away from professional study and at the age

of twenty produced, in collaboration, as is common in

France, the first of a series of dramas which continued for

fifty years. Les Dervis (1811) is usually cited as the first

play in which he took a hand, though, as for some time he

did not sign his work, identification is somewhat difficult.

He achieved no distinct success till 1816, when Une Nuit

de Garde Nationale made him in a way famous. Thence¬

forward his fertility was unceasing and its results pro¬

digious. There may be in existence a complete list of

Scribe’s works, but we have never seen any that pretended

to be such. He wrote every kind of drama—vaudevilles,

1 In a machine made by the present writer for ruling gratings the

periodic error is entirely due to the graduation and centering of the

head. The uncorrected periodic error from this cause displaces the

lines Annrth of an inch, which is sufficient to entirely ruin all gratings

made without correcting it.

XXL — 70

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (563) Page 553 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634598 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|