Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(540) Page 530

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

530

SCOTLAND

[statistics.

Roads.

Canals.

Rail¬

ways.

Communication.—In the 12th century an Act was passed provid¬

ing that the highways between market-towns should be at least

20 feet broad. Over the principal rivers at this early period there

were bridges near the most populous places, as over the Dee near

Aberdeen, the Esk at Brechin, the Tay at Perth, and the Forth

near Stirling. Until the 16th century, however, traffic between

distant places was carried on chiefly by pack-horses. The first

stage-coach in Scotland was that which ran between Edinburgh

and Leith in 1610. In 1658 there was a fortnightly stage-coach

between Edinburgh and London, but afterwards it would appear

to have been discontinued for many years. Separate Acts en¬

joining the justices of the peace, and afterwards along with

them the commissioners of supply, to take measures for the

maintenance of roads were passed in 1617, 1669, 1676, and

1686. These provisions had reference chiefly to what afterwards

came to be known as “statute labour roads,” intended primarily

to supply a means of communication within the several parishes.

They were kept in repair by the tenants and cotters, and, when

their labour was not sufficient, by the landlords, who were required

to “ stent ” (assess) themselves, customs also being sometimes levied

at bridges, ferries, and causeways. By separate local Acts the

“statute labour” was in many cases converted into a payment

called “conversion money,” and the General Roads Act of 1845

made the alteration universal. By the Roads and Bridges (Scotland)

Act of 1878 the old organization for the management of these roads

was entirely superseded in 1883. The Highlands had good (mili¬

tary) roads earlier than the rest of the country. The project, begun

in 1725, took ten years to complete, and the roads were afterwards

kept in repair by an annual parliamentary grant. In the Lowlands

the main lines of roads have been constructed under the Turnpike

Acts, the earliest of which was obtained in 1750. Originally they

were maintained by tolls exacted from those who used them ; but

this method was—after several counties had obtained separate

Acts for its abolition—superseded throughout Scotland in 1883

by the general Act of 1878, providing for the maintenance of all

classes of roads by assessment levied by the county road trustees.

Scotland possesses two canals constructed primarily to abridge

the sea passage round the coast, —the Caledonian and the Crinan.

The Caledonian Canal, extending from south-west to north-east,

a distance of 60 miles along the line of lochs from Loch Linnhe

on the west coast to the Moray Firth on the east coast, was

begun in 1803, opened while yet unfinished in 1822, and com¬

pleted in 1847, the total cost being about £1,300,000. Constructed

originally to afford a quicker passage for ships to the east coast of

Scotland and the coasts of Europe, it has, owing to the increased

size of vessels, ceased to fulfil this purpose, its chief service having

been in opening up a picturesque route for tourists, assisting local

trade, and affording a passage for fishing boats between the east

and west coasts. The Crinan Canal, stretching across the Mull of

Cantyre from Loch Gilp to Jura Sound, a distance of 9 miles, and

admitting the passage of vessels of 200 tons burden, was opened in

1801 at a cost of over £100,000. The principal boat canals are the

Forth and Clyde or Great Canal, begun in 1798, between Grange¬

mouth on the Forth and Bowling on the Clyde, a distance of 30|

miles, with a branch to Port Dundas, making the total distance

33f miles ; the Union Canal between Edinburgh and the Forth and

Clyde Canal at Port Dundas, near Glasgow, completed in 1822 ; and

the Monkland Canal, completed in 1791, connecting Glasgow with

the Monkland mineral district and communicating with a lateral

branch of the Forth and Clyde Canal at Port Dundas. Several

other canals in Scotland have been superseded by railway routes.

The first railway in Scotland for which an Act of Parliament

was obtained was that between Kilmarnock and Troon (9| miles),

opened in 1812, and of course worked by horses. A similar rail¬

way, of which the chief source of profit was the passenger traffic,

was opened between Edinburgh and Dalkeith in 1831, branches

being afterwards extended to Leith and Musselburgh. By 1840

the length of the railway lines in Scotland for which Bills were

passed was 191J miles, the capital being £3,122,133. The chief

railway companies in Scotland are the Caledonian, formed in 1845,

total capital in 1884-85 £37,999,933; the North British, of the same

date, total capital £32,821,526 ; the Glasgow and South-Western,

formed by amalgamation in 1850, total capital £13,230,849 ;

the Highland, formed by amalgamation in 1865, total capital

£4,445,316 ; and the Great North of Scotland, 1846, total capital

£4,869,983. The management of the small branch lines belonging

to local companies is generally undertaken by the larger companies.

By 1849 there were 795 miles of railway in Scotland. The follow¬

ing table (X.) shows the progress since 1857 (see also Railway,

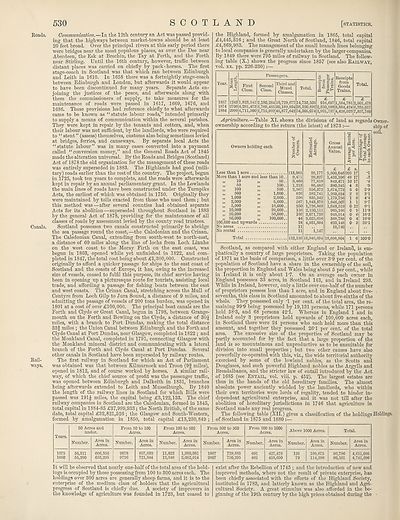

vol. xx. pp. 226-230):—

Year.

1857

1874

1884

1243

2700

2999

Passengers.

First

Class.

1,823,542

4,261,473

4,711,500

Second

Class.

2,180,284

3,769,485

2,715,932

Third and

Mixed

Classes.

10,729,677

30,189,934

46,877,642

Total.

14,733,503

38,220,892

54,305,074

•&0 “c

s a |-g

£

916,'

2,350,593

2,931,737

Receipts

from

Goods

Trains.

Total.

£ £

1,584,781 2,501,478

3,884,424 6,235,017

4,426,0237,357,760

Agriculture.—Table XL shows the divisions of land as regards Owner-

ownership according to the return (the latest) of 1873 :— ship of

Owners holding each

Less than 1 acre

More than 1 acre and less than 10.

10

50

100

500

1,000

2,000

5,000

10,000

20,000

50,000

000 and upwards

No areas

No rental

100

50.

100.

500.

1,000.

2,000.

5,000.

10,000.

20,000.

50,000.

100,000.

113,005

9,471

3,469

1,213

2,367

826

596

587

250

159

103

44

24

11

11

Total 132,136 18,946,694 18,698,804

S £

28,177

29,327

77,619

86,483

556,372

582,741

835,242

1,843,378

1,726,869

2,150,111

3,071,728

3,025,616

4,931,884

i,147

Gross

Annual

Value.

£

5,800,046

1,433,106

843,471

380,345

1,674,773

1,263,524

1,179,756

1,946,507

1,043,519

965,166

945,914

588,788

623,148

10,740

<1

O SO®

03 c4 G

*3°

P*H o

£ s.

205 17

48 17

10 17

4 8

3

2

1

1

0 12

0 9

0 6

0 4

0 3

•1

.2

•4

•5

2-9

ST

4'4

9-7

9T

11-3

16-2

16-0

26T

1 0 100-0

soil.

Scotland, as compared with either England or Ireland, is em¬

phatically a country of large proprietors. Taking the population

of 1871 as the basis of comparison, a little over 3'9 per cent, of the

population of Scotland have a share in the ownership of the soil,

the proportion in England and Wales being about 5 per cent., while

in Ireland it is only about 1'7. On an average each owner in

England possesses 33 acres, in Scotland 143, and in Ireland 293.

While in Ireland, however, only a little over one-half of the number

of proprietors possess less than 1 acre, and in England about five- .

sevenths, this class in Scotland amounted to about five-sixths of the

whole. They possessed only -1 per cent, of the total area, the re¬

maining 99-9 being possessed by 19,131 persons, while 171 persons

held 58'3, and 68 persons 42-1. Whereas in England 1 and in

Ireland only 3 proprietors held upwards of 100,000 acres each,

in Scotland there were 24 persons who each held more than this

amount, and together they possessed 26T per cent, of the total

area. The excessive size of the properties of Scotland may be

partly accounted for by the fact that a large proportion of the

land is so mountainous and unproductive as to be unsuitable for

division into small properties ; but two other causes have also

powerfully co-operated with this, viz., the wide territorial authority

exercised by some of the lowland nobles, as the Scotts and

Douglases, and such powerful Highland nobles as the Argylls and

Breadalbanes, and the stricter law of entail introduced by the Act

of 1685 (see Entail, vol. viii. p. 452). The largest estates are

thus in the hands of the old hereditary families. The almost

absolute power anciently wielded by the landlords, who within

their own territories were lords of regality, tended to hinder in¬

dependent agricultural enterprise, and it was not till after the

abolition of hereditary jurisdictions in 1746 that agriculture in

Scotland made any real progress.

The following table (XII.) gives a classification of the holdings Holdings,

of Scotland in 1875 and 1880 :—

Years.

50 Acres and

under.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

From 50 to 100

Acres.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

From 100 to 300

Acres.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

From 300 to 500

Acres.

Area in

Acres.

From 500 to 1000

Acres.

a™"

Above 1000 Acres.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

Total.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

1875

1880

56,311

55,280

666,356

653,295

697,620

721,844

11,823

12,348

1,980,081

2,082,914

1967

2007

729,885

750,295

691

661

427,478

418,650

126

79

109,675

114,298

80,796

80,101

4,611,095

4,741,296

It will be observed that nearly one-half of the total area of the hold¬

ings is occupied by those possessing from 100 to 300 acres each. The

holdings over 300 acres are generally sheep farms, and it is to the

enterprise of the medium class of holders that the agricultural

progress of Scotland is chiefly due. A society of improvers in

the knowledge of agriculture was founded in 1723, but ceased to

exist after the Rebellion of 1745 ; and the introduction of new and

improved methods, where not the result of private enterprise, has

been chiefly associated with the efforts of the Highland Society,

instituted in 1783, and latterly known as the Highland and Agri¬

cultural Society. A great stimulus was also afforded in the be¬

ginning of the 19th century by the high prices obtained during the

SCOTLAND

[statistics.

Roads.

Canals.

Rail¬

ways.

Communication.—In the 12th century an Act was passed provid¬

ing that the highways between market-towns should be at least

20 feet broad. Over the principal rivers at this early period there

were bridges near the most populous places, as over the Dee near

Aberdeen, the Esk at Brechin, the Tay at Perth, and the Forth

near Stirling. Until the 16th century, however, traffic between

distant places was carried on chiefly by pack-horses. The first

stage-coach in Scotland was that which ran between Edinburgh

and Leith in 1610. In 1658 there was a fortnightly stage-coach

between Edinburgh and London, but afterwards it would appear

to have been discontinued for many years. Separate Acts en¬

joining the justices of the peace, and afterwards along with

them the commissioners of supply, to take measures for the

maintenance of roads were passed in 1617, 1669, 1676, and

1686. These provisions had reference chiefly to what afterwards

came to be known as “statute labour roads,” intended primarily

to supply a means of communication within the several parishes.

They were kept in repair by the tenants and cotters, and, when

their labour was not sufficient, by the landlords, who were required

to “ stent ” (assess) themselves, customs also being sometimes levied

at bridges, ferries, and causeways. By separate local Acts the

“statute labour” was in many cases converted into a payment

called “conversion money,” and the General Roads Act of 1845

made the alteration universal. By the Roads and Bridges (Scotland)

Act of 1878 the old organization for the management of these roads

was entirely superseded in 1883. The Highlands had good (mili¬

tary) roads earlier than the rest of the country. The project, begun

in 1725, took ten years to complete, and the roads were afterwards

kept in repair by an annual parliamentary grant. In the Lowlands

the main lines of roads have been constructed under the Turnpike

Acts, the earliest of which was obtained in 1750. Originally they

were maintained by tolls exacted from those who used them ; but

this method was—after several counties had obtained separate

Acts for its abolition—superseded throughout Scotland in 1883

by the general Act of 1878, providing for the maintenance of all

classes of roads by assessment levied by the county road trustees.

Scotland possesses two canals constructed primarily to abridge

the sea passage round the coast, —the Caledonian and the Crinan.

The Caledonian Canal, extending from south-west to north-east,

a distance of 60 miles along the line of lochs from Loch Linnhe

on the west coast to the Moray Firth on the east coast, was

begun in 1803, opened while yet unfinished in 1822, and com¬

pleted in 1847, the total cost being about £1,300,000. Constructed

originally to afford a quicker passage for ships to the east coast of

Scotland and the coasts of Europe, it has, owing to the increased

size of vessels, ceased to fulfil this purpose, its chief service having

been in opening up a picturesque route for tourists, assisting local

trade, and affording a passage for fishing boats between the east

and west coasts. The Crinan Canal, stretching across the Mull of

Cantyre from Loch Gilp to Jura Sound, a distance of 9 miles, and

admitting the passage of vessels of 200 tons burden, was opened in

1801 at a cost of over £100,000. The principal boat canals are the

Forth and Clyde or Great Canal, begun in 1798, between Grange¬

mouth on the Forth and Bowling on the Clyde, a distance of 30|

miles, with a branch to Port Dundas, making the total distance

33f miles ; the Union Canal between Edinburgh and the Forth and

Clyde Canal at Port Dundas, near Glasgow, completed in 1822 ; and

the Monkland Canal, completed in 1791, connecting Glasgow with

the Monkland mineral district and communicating with a lateral

branch of the Forth and Clyde Canal at Port Dundas. Several

other canals in Scotland have been superseded by railway routes.

The first railway in Scotland for which an Act of Parliament

was obtained was that between Kilmarnock and Troon (9| miles),

opened in 1812, and of course worked by horses. A similar rail¬

way, of which the chief source of profit was the passenger traffic,

was opened between Edinburgh and Dalkeith in 1831, branches

being afterwards extended to Leith and Musselburgh. By 1840

the length of the railway lines in Scotland for which Bills were

passed was 191J miles, the capital being £3,122,133. The chief

railway companies in Scotland are the Caledonian, formed in 1845,

total capital in 1884-85 £37,999,933; the North British, of the same

date, total capital £32,821,526 ; the Glasgow and South-Western,

formed by amalgamation in 1850, total capital £13,230,849 ;

the Highland, formed by amalgamation in 1865, total capital

£4,445,316 ; and the Great North of Scotland, 1846, total capital

£4,869,983. The management of the small branch lines belonging

to local companies is generally undertaken by the larger companies.

By 1849 there were 795 miles of railway in Scotland. The follow¬

ing table (X.) shows the progress since 1857 (see also Railway,

vol. xx. pp. 226-230):—

Year.

1857

1874

1884

1243

2700

2999

Passengers.

First

Class.

1,823,542

4,261,473

4,711,500

Second

Class.

2,180,284

3,769,485

2,715,932

Third and

Mixed

Classes.

10,729,677

30,189,934

46,877,642

Total.

14,733,503

38,220,892

54,305,074

•&0 “c

s a |-g

£

916,'

2,350,593

2,931,737

Receipts

from

Goods

Trains.

Total.

£ £

1,584,781 2,501,478

3,884,424 6,235,017

4,426,0237,357,760

Agriculture.—Table XL shows the divisions of land as regards Owner-

ownership according to the return (the latest) of 1873 :— ship of

Owners holding each

Less than 1 acre

More than 1 acre and less than 10.

10

50

100

500

1,000

2,000

5,000

10,000

20,000

50,000

000 and upwards

No areas

No rental

100

50.

100.

500.

1,000.

2,000.

5,000.

10,000.

20,000.

50,000.

100,000.

113,005

9,471

3,469

1,213

2,367

826

596

587

250

159

103

44

24

11

11

Total 132,136 18,946,694 18,698,804

S £

28,177

29,327

77,619

86,483

556,372

582,741

835,242

1,843,378

1,726,869

2,150,111

3,071,728

3,025,616

4,931,884

i,147

Gross

Annual

Value.

£

5,800,046

1,433,106

843,471

380,345

1,674,773

1,263,524

1,179,756

1,946,507

1,043,519

965,166

945,914

588,788

623,148

10,740

<1

O SO®

03 c4 G

*3°

P*H o

£ s.

205 17

48 17

10 17

4 8

3

2

1

1

0 12

0 9

0 6

0 4

0 3

•1

.2

•4

•5

2-9

ST

4'4

9-7

9T

11-3

16-2

16-0

26T

1 0 100-0

soil.

Scotland, as compared with either England or Ireland, is em¬

phatically a country of large proprietors. Taking the population

of 1871 as the basis of comparison, a little over 3'9 per cent, of the

population of Scotland have a share in the ownership of the soil,

the proportion in England and Wales being about 5 per cent., while

in Ireland it is only about 1'7. On an average each owner in

England possesses 33 acres, in Scotland 143, and in Ireland 293.

While in Ireland, however, only a little over one-half of the number

of proprietors possess less than 1 acre, and in England about five- .

sevenths, this class in Scotland amounted to about five-sixths of the

whole. They possessed only -1 per cent, of the total area, the re¬

maining 99-9 being possessed by 19,131 persons, while 171 persons

held 58'3, and 68 persons 42-1. Whereas in England 1 and in

Ireland only 3 proprietors held upwards of 100,000 acres each,

in Scotland there were 24 persons who each held more than this

amount, and together they possessed 26T per cent, of the total

area. The excessive size of the properties of Scotland may be

partly accounted for by the fact that a large proportion of the

land is so mountainous and unproductive as to be unsuitable for

division into small properties ; but two other causes have also

powerfully co-operated with this, viz., the wide territorial authority

exercised by some of the lowland nobles, as the Scotts and

Douglases, and such powerful Highland nobles as the Argylls and

Breadalbanes, and the stricter law of entail introduced by the Act

of 1685 (see Entail, vol. viii. p. 452). The largest estates are

thus in the hands of the old hereditary families. The almost

absolute power anciently wielded by the landlords, who within

their own territories were lords of regality, tended to hinder in¬

dependent agricultural enterprise, and it was not till after the

abolition of hereditary jurisdictions in 1746 that agriculture in

Scotland made any real progress.

The following table (XII.) gives a classification of the holdings Holdings,

of Scotland in 1875 and 1880 :—

Years.

50 Acres and

under.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

From 50 to 100

Acres.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

From 100 to 300

Acres.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

From 300 to 500

Acres.

Area in

Acres.

From 500 to 1000

Acres.

a™"

Above 1000 Acres.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

Total.

Number.

Area in

Acres.

1875

1880

56,311

55,280

666,356

653,295

697,620

721,844

11,823

12,348

1,980,081

2,082,914

1967

2007

729,885

750,295

691

661

427,478

418,650

126

79

109,675

114,298

80,796

80,101

4,611,095

4,741,296

It will be observed that nearly one-half of the total area of the hold¬

ings is occupied by those possessing from 100 to 300 acres each. The

holdings over 300 acres are generally sheep farms, and it is to the

enterprise of the medium class of holders that the agricultural

progress of Scotland is chiefly due. A society of improvers in

the knowledge of agriculture was founded in 1723, but ceased to

exist after the Rebellion of 1745 ; and the introduction of new and

improved methods, where not the result of private enterprise, has

been chiefly associated with the efforts of the Highland Society,

instituted in 1783, and latterly known as the Highland and Agri¬

cultural Society. A great stimulus was also afforded in the be¬

ginning of the 19th century by the high prices obtained during the

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (540) Page 530 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193634299 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|