Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(94) Page 84

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

“ Artels.

84

II U S S I A

shown that no redistribution is made without urgent necessity,

dhus, to quote but one instance, in 4442 village communities of

Moscow, the average number of redistributions has been 2'1 in

twenty years (1858-78), and in more than two-thirds of these

communities the redistribution took place only once. On the

other hand, a regular rotation of all households over all lots, in

order to equalize the remaining minor inequalities, is very often

practised in the black-earth region, where no manure is needed.

Besides the arable mark, there is usually a vygon (or “ common ”)

for grazing, to which all householders send their cattle, whatever

the number they possess. The meadows are either divided on the

above principles, or mowed in common, and the hay divided

according to the number of lots. The forests, when consisting of

small wood in sufficient quantity, are laid under no regulations;

when this is scarce, every trunk is counted, and valued according

to its age, number of branches, &c., and the whole is divided accord¬

ing to the number of lots.

_ The houses and the orchards behind them belong also, in prin¬

ciple, to the community ; but no peredyel is made, except after a

fire or when the necessity arises of building the houses at greater

distances apart. The orchards usually remain for years in the

same hands, with but slow equalizations of the lots in width.

All decisions in the village community are given by the mir,

that is, by the general assembly of all householders,—women being

admitted on an equal footing with men, -when widows, or when their

male guardians are absent. For the decisions unanimity is neces¬

sary ; and, though in some difficult cases of a general peredyel the

discussions may last for two or three days, no decision is reached

until the minority has declared its agreement with the majority.

Each commune elects an elder (starosta); he is the executive,

but has no authority apart from that of the mir whose decisions

he carries out. All attempts on the part of the Government to

make him a functionary have failed.

Opinion as to the advantages and disadvantages of the village

community being much divided in Russia, it has been within the

last twenty years the subject of extensive inquiry, both private

and official, and of an ever-growing literature and polemic. The

supporters of the mir are found chiefly among those who have made

more or less extensive inquiries into its actual organization and con¬

sequences, while their opponents draw their arguments principally

from theoretical considerations of political economy. The main

reproach that it checks individual development and is a source of

immobility has been shaken of late by a better knowledge of the

institution, which has brought to light its remarkable plasticity and

powder of adaptation to new circumstances. The free settlers in

Siberia have voluntarily introduced the same organization. In north

and north-east Russia, where arable land is scattered in small patches

among forests, communities of several villages, or “ volost ” com¬

munities, have arisen; and in the “ voisko ” of the Ural Cossacks we

find community of the whole territory as regards both land and fish¬

eries and work in common. Nay, the German colonists of southern

Russia, who set out with the principle of personal property, have sub¬

sequently introduced that of the village community, adapted to their

special needs (Clauss). In some localities, where there was no great

scarcity of land and the authorities did not interfere, joint cultiva¬

tion of a common area for filling the storehouses has recently been

developed (in Penza 974 communes have introduced this system and

[village communities.

cultivate an aggregate of 26,910 acres). The renting of land in

OO o 7 XV-'XXUALig V-71 IdllLl 111

common,or even purchase of land by wealthy communes, has become

quite usual, as also the purchase in common of agricultural imple¬

ments. r

Since the emancipation of the serfs, however, the mir has been

undergoing profound modifications. The differences of wealth

which ensued,—the impoverishment of the mass, the rapid increase

of the rural proletariat, and the enrichment of a few' “kulaks”

and “miroyedes” (“ mir-eaters ”),—are certainly operating un¬

favourably for the mir. The miroyedes steadily strive to break up

the organization of the commune as an obstacle to the extension

of their power over the moderately well-to-do peasants ; while the

proletariat cares little about the mir. Fears on the one side and

hopes on the other have been thus entertained as to the likelihood

of the mir resisting these disintegrating influences, favoured, more¬

over, by those landowners and manufacturers who foresee in the

creation of a rural proletariat the certainty of cheap labour. But

the village community does not appear as yet to have lost the power

of adaptation which it has exhibited throughout its history. If,

indeed, the impoverishment of the peasants continues to go on, and

legislation also, interferes with the mir, it must of course disap¬

pear, but not without a corresponding disturbance in Russian life.1

The co-operative spirit of the Great Russians shows itself further

i See Collection of Materials on Village Communities, published by the Geogra-

a^Ci ®conorn'cal Societies, vol. i. (containing a complete bibliography up to

1880). Of more recent works the following are worthy of notice :—Lutchitsky

Collectwn of Materials for the History of the Village Community in the Ukraine,

Kieit, 1884; Efimenko, Researches into Popular Life, 1884; Hantower On the

Origin of the Czinsz Possession, 1884; Samokvasoff, History of Russian Law, 1884;

Keus.sler.ATur Geschichte und Kritik desbauerlichen G emeinde-Resit zes in Russland,

1 vols., 1884; and papers in publications of Geographical Society.

in another sphere in the artels, which have also been a prominent

feature of Russian life since the dawn of history. The artel verv

much resembles the co-operative society of western Europe, with this

difference that it makes its appearance without any impulse from

theory, simply as a natural form of popular life. When workmen

from any province come, for instance, to St Petersburg to ensure

in the textile industries, or to wrork as carpenters, masons &c

they immediately unite in groups of from ten to fifty persons’

settle in a house together, keep a common table, and pay each his

Part of the expense to the elected elder of the artel. All Russia is

covered with such artels,—in the cities, in the forests, on the banks

ot rivers, on journeys, and even in the prisons.

The industrial artel is almost as frequent as the preceding in all

those trades which admit ot it. A social history of the most funda¬

mental state of Russian society would be a history of their hunting

fishing, shipping, trading, building, exploring art els. Artels of one

or two hundred carpenters, bricklayers, &c., are common wherever

new buildings have to be erected, or railways or bridges made • the

contractors always prefer to deal with an artel, rather than’with

separate workmen. The same principles are often put into practice

in the domestic trades. It is needless to add that the wages divided

by the artels are higher than those earned by isolated workmen

Finally, a great number of artels on the stock exchange, in the

seaports, in the great cities (commissionaires), during the great

fairs, and on railways have grown up of late, and have acquired

the confidence of tradespeople to such an extent that considerable

sums of money and complicated banking operations are frequently

handed over to an artelshik (member of an artel) without any

receipt, his number or his name being accepted as sufficient

guarantee. These artels are recruited only on personal acquaint¬

ance with the candidates for membership, and security r each in o-

£80 to £100 is exacted in the exchange artels. These last have a

tendency to become mere joint-stock companies employing salaried

servants. Co-operative societies have lately been organized by

several zemstvos. They have achieved good results, but do not

exhibit, on the whole, the same unity of organization as those which

have arisen in a natural way among peasants and artisans.2

The chief occupation of the population of Russia is agriculture Atrri

Only in a few parts of Moscow, Vladimir, and Nijni has it been culture

abandoned for manufacturing pursuits. Cattle-breeding is the

leading industry in the Steppe region, the timber-trade in the

north-east, and fishing on the White and Caspian Seas. Of the

total surface of Russia, 1,237,360,000 acres (excluding Finland),

1,018,737,000 acres are registered, and it appears that 39'9 per

cent, of these belongs to the crown, 1-9 to the domains (udel)

31‘2 to peasants, 247 to landed proprietors or to private com¬

panies, and 2'3 to the towns and monasteries. Of the acres

registered only 592,650,000 can be considered as “good,” that is

capable of paying the land tax; and of these 248,630,000 acres

were under crops in 1884.3 The crops of 1883 were those of an

average year, that is, 2‘9 to 1 in central Russia, and 4 to 1 in

south Russia, and were estimated as follows (seed corn being left

out of account):—Rye, 49,185,000 quarters; wheat, 21,605 000-

oats, 50,403,000 ; barley, 13,476,000 ; other grains, 18,808,000.’

Those of 1884 (a very good year) reached an average of 18 per

cent, higher, except oats. The crops are, however, very unequally

distributed. In an average year there are 8 governments which

are some 6,930,000 quarters short of their requirements, 35 which

have an excess of 33,770,000 quarters, and 17 which have neither

excess nor deficiency. The export of corn from Russia is steadily

increasing, having risen from 6,560,000 quarters in 1856-60 to an

average of 23,700,000 quarters in 1876-83 and 26,623,700 quarters

in 1884. This increase does not prove, however, an excess of

corn, for even when one-third of Russia was famine-stricken, durhm

the last years of scarcity, the export trade did not decline ; even

Samara exported during the last famine there, the peasants being

compelled to sell their corn in autumn to pay their taxes. Scarcity

is quite usual, the food supply of some ten provinces being

exhausted every year by the end of the spring. Orach, and even

bark, are then mixed with flour for making bread.

Flax, both for yarn and seed, is extensively grown in the north¬

west and west, and the annual production is estimated at 6,400 000

cwts. of fibre and 2,900,000 quarters of linseed. Hemp is largely

cultivated in the central governments, the yearly production being

2 See Isaeff cm Artels in Russia, and in Appendix to Russian translation of

Reclus; Kaiatclioff, The Artels of Old and New Russia ; Recueil of Materials on

Artels (2vols.); Sclierbina, South Russian Artels-, Nemiroff, Stock Exchange

Artels (all Russian).

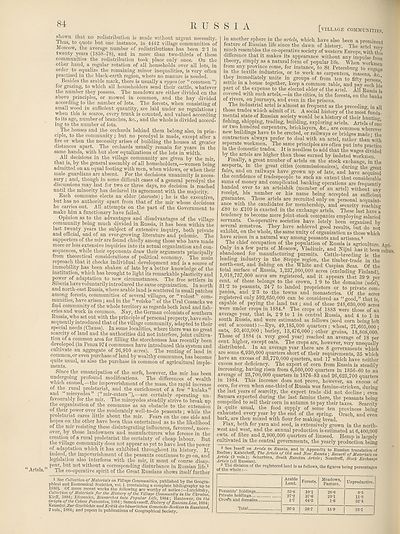

3 The dirision of the registered land is as follows, the figures being percentages

of the whole:—

Peasants’ holdings...

Private holdings

Crovfti and domains..

Total.

Arable

Land.

S3-8

27-2

1-7

Forests.

10-1

37-6

64-3

Meadows,

Pasture.

26-6

231

1-6

Unproductive,

9-5

11-9

32-4

84

II U S S I A

shown that no redistribution is made without urgent necessity,

dhus, to quote but one instance, in 4442 village communities of

Moscow, the average number of redistributions has been 2'1 in

twenty years (1858-78), and in more than two-thirds of these

communities the redistribution took place only once. On the

other hand, a regular rotation of all households over all lots, in

order to equalize the remaining minor inequalities, is very often

practised in the black-earth region, where no manure is needed.

Besides the arable mark, there is usually a vygon (or “ common ”)

for grazing, to which all householders send their cattle, whatever

the number they possess. The meadows are either divided on the

above principles, or mowed in common, and the hay divided

according to the number of lots. The forests, when consisting of

small wood in sufficient quantity, are laid under no regulations;

when this is scarce, every trunk is counted, and valued according

to its age, number of branches, &c., and the whole is divided accord¬

ing to the number of lots.

_ The houses and the orchards behind them belong also, in prin¬

ciple, to the community ; but no peredyel is made, except after a

fire or when the necessity arises of building the houses at greater

distances apart. The orchards usually remain for years in the

same hands, with but slow equalizations of the lots in width.

All decisions in the village community are given by the mir,

that is, by the general assembly of all householders,—women being

admitted on an equal footing with men, -when widows, or when their

male guardians are absent. For the decisions unanimity is neces¬

sary ; and, though in some difficult cases of a general peredyel the

discussions may last for two or three days, no decision is reached

until the minority has declared its agreement with the majority.

Each commune elects an elder (starosta); he is the executive,

but has no authority apart from that of the mir whose decisions

he carries out. All attempts on the part of the Government to

make him a functionary have failed.

Opinion as to the advantages and disadvantages of the village

community being much divided in Russia, it has been within the

last twenty years the subject of extensive inquiry, both private

and official, and of an ever-growing literature and polemic. The

supporters of the mir are found chiefly among those who have made

more or less extensive inquiries into its actual organization and con¬

sequences, while their opponents draw their arguments principally

from theoretical considerations of political economy. The main

reproach that it checks individual development and is a source of

immobility has been shaken of late by a better knowledge of the

institution, which has brought to light its remarkable plasticity and

powder of adaptation to new circumstances. The free settlers in

Siberia have voluntarily introduced the same organization. In north

and north-east Russia, where arable land is scattered in small patches

among forests, communities of several villages, or “ volost ” com¬

munities, have arisen; and in the “ voisko ” of the Ural Cossacks we

find community of the whole territory as regards both land and fish¬

eries and work in common. Nay, the German colonists of southern

Russia, who set out with the principle of personal property, have sub¬

sequently introduced that of the village community, adapted to their

special needs (Clauss). In some localities, where there was no great

scarcity of land and the authorities did not interfere, joint cultiva¬

tion of a common area for filling the storehouses has recently been

developed (in Penza 974 communes have introduced this system and

[village communities.

cultivate an aggregate of 26,910 acres). The renting of land in

OO o 7 XV-'XXUALig V-71 IdllLl 111

common,or even purchase of land by wealthy communes, has become

quite usual, as also the purchase in common of agricultural imple¬

ments. r

Since the emancipation of the serfs, however, the mir has been

undergoing profound modifications. The differences of wealth

which ensued,—the impoverishment of the mass, the rapid increase

of the rural proletariat, and the enrichment of a few' “kulaks”

and “miroyedes” (“ mir-eaters ”),—are certainly operating un¬

favourably for the mir. The miroyedes steadily strive to break up

the organization of the commune as an obstacle to the extension

of their power over the moderately well-to-do peasants ; while the

proletariat cares little about the mir. Fears on the one side and

hopes on the other have been thus entertained as to the likelihood

of the mir resisting these disintegrating influences, favoured, more¬

over, by those landowners and manufacturers who foresee in the

creation of a rural proletariat the certainty of cheap labour. But

the village community does not appear as yet to have lost the power

of adaptation which it has exhibited throughout its history. If,

indeed, the impoverishment of the peasants continues to go on, and

legislation also, interferes with the mir, it must of course disap¬

pear, but not without a corresponding disturbance in Russian life.1

The co-operative spirit of the Great Russians shows itself further

i See Collection of Materials on Village Communities, published by the Geogra-

a^Ci ®conorn'cal Societies, vol. i. (containing a complete bibliography up to

1880). Of more recent works the following are worthy of notice :—Lutchitsky

Collectwn of Materials for the History of the Village Community in the Ukraine,

Kieit, 1884; Efimenko, Researches into Popular Life, 1884; Hantower On the

Origin of the Czinsz Possession, 1884; Samokvasoff, History of Russian Law, 1884;

Keus.sler.ATur Geschichte und Kritik desbauerlichen G emeinde-Resit zes in Russland,

1 vols., 1884; and papers in publications of Geographical Society.

in another sphere in the artels, which have also been a prominent

feature of Russian life since the dawn of history. The artel verv

much resembles the co-operative society of western Europe, with this

difference that it makes its appearance without any impulse from

theory, simply as a natural form of popular life. When workmen

from any province come, for instance, to St Petersburg to ensure

in the textile industries, or to wrork as carpenters, masons &c

they immediately unite in groups of from ten to fifty persons’

settle in a house together, keep a common table, and pay each his

Part of the expense to the elected elder of the artel. All Russia is

covered with such artels,—in the cities, in the forests, on the banks

ot rivers, on journeys, and even in the prisons.

The industrial artel is almost as frequent as the preceding in all

those trades which admit ot it. A social history of the most funda¬

mental state of Russian society would be a history of their hunting

fishing, shipping, trading, building, exploring art els. Artels of one

or two hundred carpenters, bricklayers, &c., are common wherever

new buildings have to be erected, or railways or bridges made • the

contractors always prefer to deal with an artel, rather than’with

separate workmen. The same principles are often put into practice

in the domestic trades. It is needless to add that the wages divided

by the artels are higher than those earned by isolated workmen

Finally, a great number of artels on the stock exchange, in the

seaports, in the great cities (commissionaires), during the great

fairs, and on railways have grown up of late, and have acquired

the confidence of tradespeople to such an extent that considerable

sums of money and complicated banking operations are frequently

handed over to an artelshik (member of an artel) without any

receipt, his number or his name being accepted as sufficient

guarantee. These artels are recruited only on personal acquaint¬

ance with the candidates for membership, and security r each in o-

£80 to £100 is exacted in the exchange artels. These last have a

tendency to become mere joint-stock companies employing salaried

servants. Co-operative societies have lately been organized by

several zemstvos. They have achieved good results, but do not

exhibit, on the whole, the same unity of organization as those which

have arisen in a natural way among peasants and artisans.2

The chief occupation of the population of Russia is agriculture Atrri

Only in a few parts of Moscow, Vladimir, and Nijni has it been culture

abandoned for manufacturing pursuits. Cattle-breeding is the

leading industry in the Steppe region, the timber-trade in the

north-east, and fishing on the White and Caspian Seas. Of the

total surface of Russia, 1,237,360,000 acres (excluding Finland),

1,018,737,000 acres are registered, and it appears that 39'9 per

cent, of these belongs to the crown, 1-9 to the domains (udel)

31‘2 to peasants, 247 to landed proprietors or to private com¬

panies, and 2'3 to the towns and monasteries. Of the acres

registered only 592,650,000 can be considered as “good,” that is

capable of paying the land tax; and of these 248,630,000 acres

were under crops in 1884.3 The crops of 1883 were those of an

average year, that is, 2‘9 to 1 in central Russia, and 4 to 1 in

south Russia, and were estimated as follows (seed corn being left

out of account):—Rye, 49,185,000 quarters; wheat, 21,605 000-

oats, 50,403,000 ; barley, 13,476,000 ; other grains, 18,808,000.’

Those of 1884 (a very good year) reached an average of 18 per

cent, higher, except oats. The crops are, however, very unequally

distributed. In an average year there are 8 governments which

are some 6,930,000 quarters short of their requirements, 35 which

have an excess of 33,770,000 quarters, and 17 which have neither

excess nor deficiency. The export of corn from Russia is steadily

increasing, having risen from 6,560,000 quarters in 1856-60 to an

average of 23,700,000 quarters in 1876-83 and 26,623,700 quarters

in 1884. This increase does not prove, however, an excess of

corn, for even when one-third of Russia was famine-stricken, durhm

the last years of scarcity, the export trade did not decline ; even

Samara exported during the last famine there, the peasants being

compelled to sell their corn in autumn to pay their taxes. Scarcity

is quite usual, the food supply of some ten provinces being

exhausted every year by the end of the spring. Orach, and even

bark, are then mixed with flour for making bread.

Flax, both for yarn and seed, is extensively grown in the north¬

west and west, and the annual production is estimated at 6,400 000

cwts. of fibre and 2,900,000 quarters of linseed. Hemp is largely

cultivated in the central governments, the yearly production being

2 See Isaeff cm Artels in Russia, and in Appendix to Russian translation of

Reclus; Kaiatclioff, The Artels of Old and New Russia ; Recueil of Materials on

Artels (2vols.); Sclierbina, South Russian Artels-, Nemiroff, Stock Exchange

Artels (all Russian).

3 The dirision of the registered land is as follows, the figures being percentages

of the whole:—

Peasants’ holdings...

Private holdings

Crovfti and domains..

Total.

Arable

Land.

S3-8

27-2

1-7

Forests.

10-1

37-6

64-3

Meadows,

Pasture.

26-6

231

1-6

Unproductive,

9-5

11-9

32-4

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (94) Page 84 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193628501 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|