Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(91) Page 81

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

VITAL STATISTICS.]

RUSSIA

81

emjy

tio

u-

;irt;

ndi

Tchuvashes.

Tartars

Bashkirs....

Mescheriaks

Tepters

Kirghizes...

Various

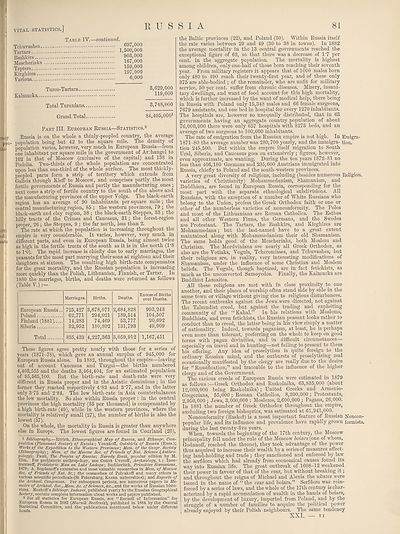

Table IV.—continued.

697,000

1,500,000

908,000

167,000

159,000

197,000

6,000

Turco-Tartars —

Kalmucks

Total Turanians.,

Grand Total

3,629,000

119,000

3,748,000

84,495,000!

Part III. European Russia—Statistics.2

Russia is on the whole a thinly-peopled country, the average

population being but 42 to the square mile. The density of

population varies, however, very much in European Russia—from

one inhabitant per square mile in the government of Archangel to

102 in that of Moscow (exclusive of the capital) and 138 in

Podolia. Two-thirds of the whole population are concentrated

upon less than one-third of the whole surface. The most thickly-

peopled parts form a strip of territory which extends from

Galicia through Kieff to Moscow, and comprises partly the most

fertile governments of Russia and partly the manufacturing ones ;

next come a strip of fertile country to the south of the above and

the manufacturing provinces of the upper Volga. The black-earth

region has an average of 90 inhabitants per square mile ; the

central manufacturing region, 85 ; the western provinces, 79 ; the

black-earth and clay region, 38 ; the black-earth Steppes, 33 ; the

hilly tracts of the Crimea and Caucasus, 31 ; the forest-region

proper, 26 ; the Steppes, 9 ; the far north, less than 2.

The rate at which the population is increasing throughout the

empire is very considerable. It varies, however, very much in

different parts, and even in European Russia, being almost twice

as high in the fertile tracts of the south as it is in the north (l-8

to TO). The rapid increase is chiefly due to early marriages, the

peasants for the most part marrying their sons at eighteen and their

daughters at sixteen. The resulting high birth-rate compensates

for the great mortality, and the Russian population is increasing

more quickly than the Polish, Lithuanian, Finnish, or Tartar. In

1880 the marriages, births, and deaths were returned as follows

(Table V.)

Marriages.

Deaths.

Excess of Births

over Deaths.

European Russia.

Poland

Finland (1881)....

Siberia

725,427

62,771

14,283

32,952

3,678,071

294,021

74,469

180,802

2,684,828

189,514

53,777

131,793

993,243

104,507

20,692

49,009

Total

835,433

4,227,363

3,059,912

1,167,451

These figures agree pretty nearly with those for a series of

years (1871-78), which gave an annual surplus of 945,000 for

European Russia alone. In 1882, throughout the empire—leaving

out of account Caucasus and Turgai—the births numbered

4,403,555 and the deaths 3,464,404, for an estimated population

of 95,565,100. But the birth-rate and death-rate were very

different in Russia proper and in the Asiatic dominions ; in the

former they reached respectively 4-83 and 3 '77; and in the latter

only 375 and 2'84. The low birth-rate in Asia counterbalances

the low mortality. So also within Russia proper : in the central

provinces the high mortality (35 per thousand) is compensated by

a high birth-rate (49), while in the western provinces, where the

mortality is relatively small (27), the number of births is also the

lowest (37).

On the whole, the mortality in Russia is greater than anywhere

else in Europe. The lowest figures are found in Courland (20),

1 Bibliography.—Rittich, Ethnographical Map of Russia, and Ethnogr. Com¬

position {Plemmnoi Sostav) of Russia ; Venukoff, Outskirts of Russia (Russ.);

Works of the Expedition to the Western Provinces; Mem. of the Oeogr. Society

(Ethnography); Mem. of the Moscow Soc. of Friends of Nat. Science (Anthro¬

pology)-, Pauli, The Peoples of Russia-, Narody Rosii, popular edition By M.

lliin. For prehistoric anthropology, see Count Uvaroff, Archgeology, i.; Inos-

trantseff, Prehistoric Man on Lake Ladoga-, Budilovitch, Primitive Slavonians,

1879; A. Bogdanotfs extensive and most valuable researches in Mem. of Moscow

Soc. of Friends of Nat. Sc.; the researches of Polyakoff and many others in

various scientific periodicals (St Petersburg, Kazan universities); and Reports of

the Archseol. Congresses. For subsequent periods, see numerous papers in Me¬

moirs of Archseol. Soc., Mem. Ac. of Sciences, &c., and the works of Russian histo¬

rians. Mezhoff’s Bibliogr. Indexes, published yearly by the Russian Geographical

Society, contain complete information about works and papers published.

2 For all statistics for European Russia, see “ Recueil of Information” for

European Russia in 1882 (Sbornik Svedeniy), published in 1884 by the Central

Statistical Committee, and the publications mentioned below under different

heads.

the Baltic provinces (22), and Poland (30). Within Russia itself

the rate varies between 29 and 49 (30 to 38 in towns). In 1882

the average mortality in the 13 central governments reached the

exceptional figure of 62, so that there was a decrease of 17 per

cent, in the aggregate population. The mortality is highest

among children, only one-half of those born reaching their seventh

year. From military registers it appears that of 1000 males born

only 480 to 490 reach their twenty-first year, and of these only

375 are able-bodied ; of the remainder, who are unfit for military

service, 50 per cent, suffer from chronic diseases. Misery, insani¬

tary dwellings, and want of food account for this high mortality,

which is further increased by the want of medical help, there being

in Russia with Poland only 15,348 males and 66 female surgeons,

7679 assistants, and one bed in hospital for every 1270 inhabitants.

The hospitals are, however so unequally distributed, that in 63

governments having an aggregate country population of about

76,000,000 there were only 657 hospitals with 8273 beds, and an

average of two surgeons to 100,000 inhabitants.

The rate of emigration from the Russian empire is not high. In Emigra-

1871-80 the average number was 280, 700 yearly, and the immigra- tion.

tion 245,500. But within the empire itself migration to South

Ural, Siberia, and Caucasus goes on extensively ; figures, however,

even approximate, are wanting. During the ten years 1872-81 no

less than 406,180 Germans and 235,600 Austrians immigrated into

Russia, chiefly to Poland and the south-western provinces.

A very great diversity of religions, including (besides numerous Religion,

varieties of Christianity) Mohammedanism, Shamanism, and

Buddhism, are found in European Russia, corresponding for the

most part with the separate ethnological subdivisions. All

Russians, with the exception of a number of White Russians who

belong to the Union, profess the Greek Orthodox faith or one or

other of the numberless varieties of nonconformity. The Poles

and most of the Lithuanians are Roman Catholics. The Esthes

and all other Western Finns, the Germans, and the Swedes

are Protestant. The Tartars, the Bashkirs, and Kirghizes are

Mohammedans; but the last-named have to a great extent

maintained along with Mohammedanism their old Shamanism.

The same holds good of the Mescheriaks, both Moslem and

Christian. The Mordvinians are nearly all Greek Orthodox, as

also are the Yotiaks, Moguls, Tcheremisses, and Tchuvashes, but

their religions are, in reality, very interesting modifications of

Shamanism, under the influence of some Christian and Moslem

beliefs. The Moguls, though baptized, are in fact fetichists, as

much as the unconverted Samoyedes. Finally, the Kalmucks are

Buddhist Lamaites.

All these religions are met with in close proximity to one

another, and their places of worship often stand side by side in the

same town or village without giving rise to religious disturbances.

The recent outbreaks against the Jews were directed, not against

the Talmudist creed, but against the trading and exploiting

community of the “Kahal.” In his relations with Moslems,

Buddhists, and even fetichists, the Russian peasant looks rather to

conduct than to creed, the latter being in his view simply a matter

of nationality. Indeed, towards paganism, at least, he is perhaps

even more than tolerant, preferring on the whole to keep on good

terms with pagan divinities, and in difficult circumstances—

especially on travel and in hunting—not failing to present to them

his offering. Any idea of proselytism is quite foreign to the

ordinary Russian mind, and the outbursts of proselytizing zeal

occasionally manifested by the clergy are really due to the desire

for “Russification,” and traceable to the influence of the higher

clergy and of the Government.

The various creeds of European Russia were estimated in 1879

as follows :—Greek Orthodox and Raskolniks, 63,835,000 (about

12,000,000 being Raskolniks) ; United Greeks and Armenio-

Gregorians, 55,000 ; Roman Catholics, 8,300,000 ; Protestants,

2,950,000 ; Jews, 3,000,000 ; Moslems, 2,600,000 ; Pagans, 26,000.

In 1881 the number of Greek Orthodox throughout the empire,

excluding two foreign bishoprics, was estimated at 61,941,000.

Nonconformity (Raskot) is a most important feature of Russian Noncon-

popular life, and its influence and prevalence have rapidly grown formists.

during the last twenty-five years.

When, towards the beginning of the 17th century, the Moscow

principality fell under the rule of the Moscow boiars (one of whom,

Godunoff, reached the throne), they took advantage of the power

thus acquired to increase their wealth by a series of measures affect¬

ing land-holding and trade ; they sanctioned and enforced by law

the serfdom which had already "from economical causes found its

way into Russian life. The great outbreak of 1608-12 weakened

their power in favour of that of the czar, but without breaking it;

and throughout the reigns of Michael and Alexis the ukazes were

issued in the name of “the czar and boiars.” Serfdom was rein¬

forced by a series of laws, and the whole of the 17th century is char¬

acterized by a rapid accumulation of wealth in the hands of boiars,

by the development of luxury, imported from Poland, and by the

struggle of a number of families to acquire the political power

| already enjoyed by their Polish neighbours. The same tendency

RUSSIA

81

emjy

tio

u-

;irt;

ndi

Tchuvashes.

Tartars

Bashkirs....

Mescheriaks

Tepters

Kirghizes...

Various

Table IV.—continued.

697,000

1,500,000

908,000

167,000

159,000

197,000

6,000

Turco-Tartars —

Kalmucks

Total Turanians.,

Grand Total

3,629,000

119,000

3,748,000

84,495,000!

Part III. European Russia—Statistics.2

Russia is on the whole a thinly-peopled country, the average

population being but 42 to the square mile. The density of

population varies, however, very much in European Russia—from

one inhabitant per square mile in the government of Archangel to

102 in that of Moscow (exclusive of the capital) and 138 in

Podolia. Two-thirds of the whole population are concentrated

upon less than one-third of the whole surface. The most thickly-

peopled parts form a strip of territory which extends from

Galicia through Kieff to Moscow, and comprises partly the most

fertile governments of Russia and partly the manufacturing ones ;

next come a strip of fertile country to the south of the above and

the manufacturing provinces of the upper Volga. The black-earth

region has an average of 90 inhabitants per square mile ; the

central manufacturing region, 85 ; the western provinces, 79 ; the

black-earth and clay region, 38 ; the black-earth Steppes, 33 ; the

hilly tracts of the Crimea and Caucasus, 31 ; the forest-region

proper, 26 ; the Steppes, 9 ; the far north, less than 2.

The rate at which the population is increasing throughout the

empire is very considerable. It varies, however, very much in

different parts, and even in European Russia, being almost twice

as high in the fertile tracts of the south as it is in the north (l-8

to TO). The rapid increase is chiefly due to early marriages, the

peasants for the most part marrying their sons at eighteen and their

daughters at sixteen. The resulting high birth-rate compensates

for the great mortality, and the Russian population is increasing

more quickly than the Polish, Lithuanian, Finnish, or Tartar. In

1880 the marriages, births, and deaths were returned as follows

(Table V.)

Marriages.

Deaths.

Excess of Births

over Deaths.

European Russia.

Poland

Finland (1881)....

Siberia

725,427

62,771

14,283

32,952

3,678,071

294,021

74,469

180,802

2,684,828

189,514

53,777

131,793

993,243

104,507

20,692

49,009

Total

835,433

4,227,363

3,059,912

1,167,451

These figures agree pretty nearly with those for a series of

years (1871-78), which gave an annual surplus of 945,000 for

European Russia alone. In 1882, throughout the empire—leaving

out of account Caucasus and Turgai—the births numbered

4,403,555 and the deaths 3,464,404, for an estimated population

of 95,565,100. But the birth-rate and death-rate were very

different in Russia proper and in the Asiatic dominions ; in the

former they reached respectively 4-83 and 3 '77; and in the latter

only 375 and 2'84. The low birth-rate in Asia counterbalances

the low mortality. So also within Russia proper : in the central

provinces the high mortality (35 per thousand) is compensated by

a high birth-rate (49), while in the western provinces, where the

mortality is relatively small (27), the number of births is also the

lowest (37).

On the whole, the mortality in Russia is greater than anywhere

else in Europe. The lowest figures are found in Courland (20),

1 Bibliography.—Rittich, Ethnographical Map of Russia, and Ethnogr. Com¬

position {Plemmnoi Sostav) of Russia ; Venukoff, Outskirts of Russia (Russ.);

Works of the Expedition to the Western Provinces; Mem. of the Oeogr. Society

(Ethnography); Mem. of the Moscow Soc. of Friends of Nat. Science (Anthro¬

pology)-, Pauli, The Peoples of Russia-, Narody Rosii, popular edition By M.

lliin. For prehistoric anthropology, see Count Uvaroff, Archgeology, i.; Inos-

trantseff, Prehistoric Man on Lake Ladoga-, Budilovitch, Primitive Slavonians,

1879; A. Bogdanotfs extensive and most valuable researches in Mem. of Moscow

Soc. of Friends of Nat. Sc.; the researches of Polyakoff and many others in

various scientific periodicals (St Petersburg, Kazan universities); and Reports of

the Archseol. Congresses. For subsequent periods, see numerous papers in Me¬

moirs of Archseol. Soc., Mem. Ac. of Sciences, &c., and the works of Russian histo¬

rians. Mezhoff’s Bibliogr. Indexes, published yearly by the Russian Geographical

Society, contain complete information about works and papers published.

2 For all statistics for European Russia, see “ Recueil of Information” for

European Russia in 1882 (Sbornik Svedeniy), published in 1884 by the Central

Statistical Committee, and the publications mentioned below under different

heads.

the Baltic provinces (22), and Poland (30). Within Russia itself

the rate varies between 29 and 49 (30 to 38 in towns). In 1882

the average mortality in the 13 central governments reached the

exceptional figure of 62, so that there was a decrease of 17 per

cent, in the aggregate population. The mortality is highest

among children, only one-half of those born reaching their seventh

year. From military registers it appears that of 1000 males born

only 480 to 490 reach their twenty-first year, and of these only

375 are able-bodied ; of the remainder, who are unfit for military

service, 50 per cent, suffer from chronic diseases. Misery, insani¬

tary dwellings, and want of food account for this high mortality,

which is further increased by the want of medical help, there being

in Russia with Poland only 15,348 males and 66 female surgeons,

7679 assistants, and one bed in hospital for every 1270 inhabitants.

The hospitals are, however so unequally distributed, that in 63

governments having an aggregate country population of about

76,000,000 there were only 657 hospitals with 8273 beds, and an

average of two surgeons to 100,000 inhabitants.

The rate of emigration from the Russian empire is not high. In Emigra-

1871-80 the average number was 280, 700 yearly, and the immigra- tion.

tion 245,500. But within the empire itself migration to South

Ural, Siberia, and Caucasus goes on extensively ; figures, however,

even approximate, are wanting. During the ten years 1872-81 no

less than 406,180 Germans and 235,600 Austrians immigrated into

Russia, chiefly to Poland and the south-western provinces.

A very great diversity of religions, including (besides numerous Religion,

varieties of Christianity) Mohammedanism, Shamanism, and

Buddhism, are found in European Russia, corresponding for the

most part with the separate ethnological subdivisions. All

Russians, with the exception of a number of White Russians who

belong to the Union, profess the Greek Orthodox faith or one or

other of the numberless varieties of nonconformity. The Poles

and most of the Lithuanians are Roman Catholics. The Esthes

and all other Western Finns, the Germans, and the Swedes

are Protestant. The Tartars, the Bashkirs, and Kirghizes are

Mohammedans; but the last-named have to a great extent

maintained along with Mohammedanism their old Shamanism.

The same holds good of the Mescheriaks, both Moslem and

Christian. The Mordvinians are nearly all Greek Orthodox, as

also are the Yotiaks, Moguls, Tcheremisses, and Tchuvashes, but

their religions are, in reality, very interesting modifications of

Shamanism, under the influence of some Christian and Moslem

beliefs. The Moguls, though baptized, are in fact fetichists, as

much as the unconverted Samoyedes. Finally, the Kalmucks are

Buddhist Lamaites.

All these religions are met with in close proximity to one

another, and their places of worship often stand side by side in the

same town or village without giving rise to religious disturbances.

The recent outbreaks against the Jews were directed, not against

the Talmudist creed, but against the trading and exploiting

community of the “Kahal.” In his relations with Moslems,

Buddhists, and even fetichists, the Russian peasant looks rather to

conduct than to creed, the latter being in his view simply a matter

of nationality. Indeed, towards paganism, at least, he is perhaps

even more than tolerant, preferring on the whole to keep on good

terms with pagan divinities, and in difficult circumstances—

especially on travel and in hunting—not failing to present to them

his offering. Any idea of proselytism is quite foreign to the

ordinary Russian mind, and the outbursts of proselytizing zeal

occasionally manifested by the clergy are really due to the desire

for “Russification,” and traceable to the influence of the higher

clergy and of the Government.

The various creeds of European Russia were estimated in 1879

as follows :—Greek Orthodox and Raskolniks, 63,835,000 (about

12,000,000 being Raskolniks) ; United Greeks and Armenio-

Gregorians, 55,000 ; Roman Catholics, 8,300,000 ; Protestants,

2,950,000 ; Jews, 3,000,000 ; Moslems, 2,600,000 ; Pagans, 26,000.

In 1881 the number of Greek Orthodox throughout the empire,

excluding two foreign bishoprics, was estimated at 61,941,000.

Nonconformity (Raskot) is a most important feature of Russian Noncon-

popular life, and its influence and prevalence have rapidly grown formists.

during the last twenty-five years.

When, towards the beginning of the 17th century, the Moscow

principality fell under the rule of the Moscow boiars (one of whom,

Godunoff, reached the throne), they took advantage of the power

thus acquired to increase their wealth by a series of measures affect¬

ing land-holding and trade ; they sanctioned and enforced by law

the serfdom which had already "from economical causes found its

way into Russian life. The great outbreak of 1608-12 weakened

their power in favour of that of the czar, but without breaking it;

and throughout the reigns of Michael and Alexis the ukazes were

issued in the name of “the czar and boiars.” Serfdom was rein¬

forced by a series of laws, and the whole of the 17th century is char¬

acterized by a rapid accumulation of wealth in the hands of boiars,

by the development of luxury, imported from Poland, and by the

struggle of a number of families to acquire the political power

| already enjoyed by their Polish neighbours. The same tendency

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (91) Page 81 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193628462 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|