Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam

(80) Page 70

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

70

K U S S I A

[administration op

Subdi¬

visions

of the

empire.

Cities.

Govern¬

ment.

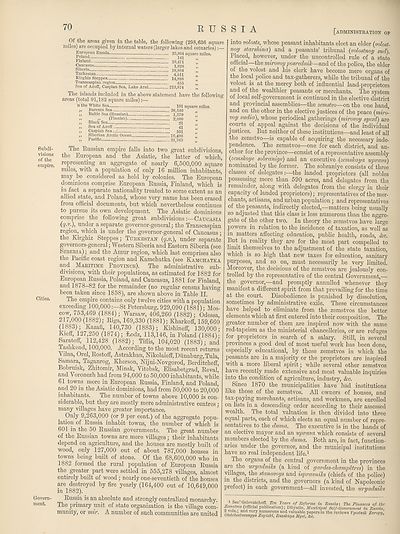

Of the areas given in the table, the following (298,636 square

miles) are occupied by internal waters (larger lakes and estuaries)

European Russia 25,804 square miles.

Poland 141

Finland 18 471

Caucasus 1628

Siberia 18’864

Turkestan 4,511

Kirghiz Steppes 14,888

Transcaspian region 455

Sea of Azoff, Caspian Sea, Lake Aral 213,874

The islands included in the above statement have the following

areas (total 91,182 square miles):—

11 the White Sea 191 square miles.

Barents Sea 35 540

Baltic Sea (Russian)., l’579 ”,

„ (Finnish) 2*000 ”

Black Sea 21

Sea of Azoff.. 41 ”

Caspian Sea..; 551 "

Siberian Arctic Ocean 16,496 ”

Pacific 3L763 ”

The Russian empire falls into two great subdivisions,

the European and the Asiatic, the latter of which,

representing an aggregate of nearly 6,500,000 square

miles, with a population of only 16 million inhabitants,

may be considered as held by colonies. The European

dominions comprise European Russia, Finland, which is

in .fact a separate nationality treated to some extent as an

allied state, and Poland, whose very name has been erased

from official documents, but which nevertheless continues

to pursue its own development. The Asiatic dominions

comprise the following great subdivisions:—Caucasia

(q.v.), under a separate governor-general; the Transcaspian

region, which is under the governor-general of Caucasus;

the Kirghiz Steppes; Turkestan (q.v.), under separate

governors-general; Western Siberia and Eastern Siberia (see

Siberia) ; and the Amur region, which last comprises also

the Pacific coast region and Kamchatka (see Kamchatka

and Maritime Province). The administrative sub¬

divisions, with their populations, as estimated for 1882 for

European Russia, Poland, and Caucasus, 1881 for Finland,

and 1878—82 for the remainder (no regular census having

been taken since 1858), are shown above in Table II.

The empire contains only twelve cities with a population

exceeding 100,000:—St Petersburg, 929,090 (1881); Mos¬

cow, 753,469 (1884); Warsaw, 406,260 (1882) ; Odessa,

217,000 (1882); Riga, 169,330 (1881); Kharkoff, 159,660

(1883); Kazan, 140,730 (1883); Kishineff, 130,000;

Kieff, 127,250 (1874); Eodz, 113,146, in Poland (1884);

Saratoff, 112,428 (1882); Tiflis, 104,020 (1883); and

Tashkend, 100,000. According to the most recent returns

Vilna, Orel, Rostoff, Astrakhan, Nikolaieff, Dunaburg, Tula,

Samara, Taganrog, Kherson, Nijni-Kovgorod, Berditcheff,

Bobruisk, Zhitomir, Minsk, Vitebsk, Elisabetgrad, Reval,

and Voronezh had from 94,000 to 50,000 inhabitants, while

61 towns more in European Russia, Finland, and Poland,

and 20 in the Asiatic dominions, had from 50,000 to 20,000

inhabitants. The number of towns above 10,000 is con¬

siderable, but they are mostly mere administrative centres;

many villages have greater importance.

Only 9,263,000 (or 9 per cent.) of the aggregate popu¬

lation of Russia inhabit towns, the number of which is

601 in the 50 Russian governments. The great number

of the Russian towns are mere villages; their inhabitants

depend on agriculture, and the houses are mostly built of

wood, only 127,000 out of about 787,000 houses in

towns being built of stone. Of the 68,600,000 who in

1882 formed the rural population of European Russia

the. greater part were settled in 555,278 villages, almost

entirely built of wood; nearly one-seventieth of the houses

are destroyed by fire yearly (164,400 out of 10,649,000

in 1882).

Russia is an absolute and strongly centralized monarchy.

The primary unit of state organization is the village com¬

munity, or mir. A number of such communities are united

into volosts, whose peasant inhabitants elect an elder (volost-

noy starshina) and a peasants’ tribunal (volostnoy sud).

Placed, however, under the uncontrolled rule of a state

official—the mirovoyposrednih—and of the police, the elder

of the volost and his clerk have become mere organs of

the local police and tax-gatherers, while the tribunal of the

volost is at the mercy both of influential land-proprietors

and of the wealthier peasants or merchants. The system

of local self-government is continued in the elective district

and provincial assemblies—the zemstvo—on the one hand,

and on the other in the elective j ustices of the peace (miro¬

voy sudia), whose periodical gatherings (mirovoy syezd) are

courts of appeal against the decisions of the individual

justices. But neither of these institutions—and least of all

the zemstvo—is capable of acquiring the necessary inde¬

pendence. The zemstvos—one for each district, and an¬

other for the province—consist of a representative assembly

(zemskoye sobraniye) and an executive (zemskaya uprava)

nominated by the former. The sobraniye consists of three

classes of delegates:—the landed proprietors (all nobles

possessing more than 590 acres, and delegates from the

remainder, along with delegates from the clergy in their

capacity of landed proprietors); representatives of the mer¬

chants, artisans, and urban population; and representatives

of the peasants, indirectly elected,—matters being usually

so adjusted that this class is less numerous than the aggre¬

gate of the other two. In theory the zemstvos have large

powers in relation to the incidence of taxation, as well as

in matters affecting education, public health, roads, &c.

But in reality they are for the most part compelled to

limit themselves to the adjustment of the state taxation,

which is so high that new taxes for education, sanitary

purposes, and so on, must necessarily be very limited.

Moreover, the decisions of the zemstvos are jealously con¬

trolled by the representative of the central Government,—

the governor,—and promptly annulled whenever they

manifest a different spirit from that prevailing for the time

at the court. Disobedience is punished by dissolution,

sometimes by administrative exile. These circumstances

have helped to eliminate from the zemstvos the better

elements which at first entered into their composition. The

greater number of them are inspired now with the same

red-tapeism as the ministerial chancelleries, or are refuges

for proprietors in search of a salary. Still, in several

provinces a good deal of most useful work has been done,

especially educational, by those zemstvos in which the

peasants are in a majority or the proprietors are inspired

with a more liberal spirit; while several other zemstvos

have recently made extensive and most valuable inquiries

into the condition of agriculture, industry, &c.

Since 18/0 the municipalities have had institutions

like those of the zemstvos. All owners of houses, and

tax-paying merchants, artisans, and workmen, are enrolled

on lists in a descending order according to their assessed

wealth. The total valuation is then divided into three

equal parts, each of which elects an equal number of repre¬

sentatives to the duma. The executive is in the hands of

an elective mayor and an uprava which consists of several

members elected by the duma. Both are, in fact, function¬

aries under the governor, and the municipal institutions

have no real independent life.1

The organs of the central government in the provinces

are the uryadniks (a kind of gardes-champetres) in the

villages, the stanovoys and ispravniks (chiefs of the police)

in the districts, and the governors (a kind of Napoleonic

prefect) in each government—all invested, the tiryadniks

bee qolovatchoff TVre Years of Reforms in Russia-, The Finances of the

zmstoos (official publication); Dityatin, Municipal Self-Government in Russia,

2 vols., and very numerous and valuable papers in the reviews Vyestnik Evropy.

Otetchestvennyya Zapt ski, Russkaya Mysl, &c.

K U S S I A

[administration op

Subdi¬

visions

of the

empire.

Cities.

Govern¬

ment.

Of the areas given in the table, the following (298,636 square

miles) are occupied by internal waters (larger lakes and estuaries)

European Russia 25,804 square miles.

Poland 141

Finland 18 471

Caucasus 1628

Siberia 18’864

Turkestan 4,511

Kirghiz Steppes 14,888

Transcaspian region 455

Sea of Azoff, Caspian Sea, Lake Aral 213,874

The islands included in the above statement have the following

areas (total 91,182 square miles):—

11 the White Sea 191 square miles.

Barents Sea 35 540

Baltic Sea (Russian)., l’579 ”,

„ (Finnish) 2*000 ”

Black Sea 21

Sea of Azoff.. 41 ”

Caspian Sea..; 551 "

Siberian Arctic Ocean 16,496 ”

Pacific 3L763 ”

The Russian empire falls into two great subdivisions,

the European and the Asiatic, the latter of which,

representing an aggregate of nearly 6,500,000 square

miles, with a population of only 16 million inhabitants,

may be considered as held by colonies. The European

dominions comprise European Russia, Finland, which is

in .fact a separate nationality treated to some extent as an

allied state, and Poland, whose very name has been erased

from official documents, but which nevertheless continues

to pursue its own development. The Asiatic dominions

comprise the following great subdivisions:—Caucasia

(q.v.), under a separate governor-general; the Transcaspian

region, which is under the governor-general of Caucasus;

the Kirghiz Steppes; Turkestan (q.v.), under separate

governors-general; Western Siberia and Eastern Siberia (see

Siberia) ; and the Amur region, which last comprises also

the Pacific coast region and Kamchatka (see Kamchatka

and Maritime Province). The administrative sub¬

divisions, with their populations, as estimated for 1882 for

European Russia, Poland, and Caucasus, 1881 for Finland,

and 1878—82 for the remainder (no regular census having

been taken since 1858), are shown above in Table II.

The empire contains only twelve cities with a population

exceeding 100,000:—St Petersburg, 929,090 (1881); Mos¬

cow, 753,469 (1884); Warsaw, 406,260 (1882) ; Odessa,

217,000 (1882); Riga, 169,330 (1881); Kharkoff, 159,660

(1883); Kazan, 140,730 (1883); Kishineff, 130,000;

Kieff, 127,250 (1874); Eodz, 113,146, in Poland (1884);

Saratoff, 112,428 (1882); Tiflis, 104,020 (1883); and

Tashkend, 100,000. According to the most recent returns

Vilna, Orel, Rostoff, Astrakhan, Nikolaieff, Dunaburg, Tula,

Samara, Taganrog, Kherson, Nijni-Kovgorod, Berditcheff,

Bobruisk, Zhitomir, Minsk, Vitebsk, Elisabetgrad, Reval,

and Voronezh had from 94,000 to 50,000 inhabitants, while

61 towns more in European Russia, Finland, and Poland,

and 20 in the Asiatic dominions, had from 50,000 to 20,000

inhabitants. The number of towns above 10,000 is con¬

siderable, but they are mostly mere administrative centres;

many villages have greater importance.

Only 9,263,000 (or 9 per cent.) of the aggregate popu¬

lation of Russia inhabit towns, the number of which is

601 in the 50 Russian governments. The great number

of the Russian towns are mere villages; their inhabitants

depend on agriculture, and the houses are mostly built of

wood, only 127,000 out of about 787,000 houses in

towns being built of stone. Of the 68,600,000 who in

1882 formed the rural population of European Russia

the. greater part were settled in 555,278 villages, almost

entirely built of wood; nearly one-seventieth of the houses

are destroyed by fire yearly (164,400 out of 10,649,000

in 1882).

Russia is an absolute and strongly centralized monarchy.

The primary unit of state organization is the village com¬

munity, or mir. A number of such communities are united

into volosts, whose peasant inhabitants elect an elder (volost-

noy starshina) and a peasants’ tribunal (volostnoy sud).

Placed, however, under the uncontrolled rule of a state

official—the mirovoyposrednih—and of the police, the elder

of the volost and his clerk have become mere organs of

the local police and tax-gatherers, while the tribunal of the

volost is at the mercy both of influential land-proprietors

and of the wealthier peasants or merchants. The system

of local self-government is continued in the elective district

and provincial assemblies—the zemstvo—on the one hand,

and on the other in the elective j ustices of the peace (miro¬

voy sudia), whose periodical gatherings (mirovoy syezd) are

courts of appeal against the decisions of the individual

justices. But neither of these institutions—and least of all

the zemstvo—is capable of acquiring the necessary inde¬

pendence. The zemstvos—one for each district, and an¬

other for the province—consist of a representative assembly

(zemskoye sobraniye) and an executive (zemskaya uprava)

nominated by the former. The sobraniye consists of three

classes of delegates:—the landed proprietors (all nobles

possessing more than 590 acres, and delegates from the

remainder, along with delegates from the clergy in their

capacity of landed proprietors); representatives of the mer¬

chants, artisans, and urban population; and representatives

of the peasants, indirectly elected,—matters being usually

so adjusted that this class is less numerous than the aggre¬

gate of the other two. In theory the zemstvos have large

powers in relation to the incidence of taxation, as well as

in matters affecting education, public health, roads, &c.

But in reality they are for the most part compelled to

limit themselves to the adjustment of the state taxation,

which is so high that new taxes for education, sanitary

purposes, and so on, must necessarily be very limited.

Moreover, the decisions of the zemstvos are jealously con¬

trolled by the representative of the central Government,—

the governor,—and promptly annulled whenever they

manifest a different spirit from that prevailing for the time

at the court. Disobedience is punished by dissolution,

sometimes by administrative exile. These circumstances

have helped to eliminate from the zemstvos the better

elements which at first entered into their composition. The

greater number of them are inspired now with the same

red-tapeism as the ministerial chancelleries, or are refuges

for proprietors in search of a salary. Still, in several

provinces a good deal of most useful work has been done,

especially educational, by those zemstvos in which the

peasants are in a majority or the proprietors are inspired

with a more liberal spirit; while several other zemstvos

have recently made extensive and most valuable inquiries

into the condition of agriculture, industry, &c.

Since 18/0 the municipalities have had institutions

like those of the zemstvos. All owners of houses, and

tax-paying merchants, artisans, and workmen, are enrolled

on lists in a descending order according to their assessed

wealth. The total valuation is then divided into three

equal parts, each of which elects an equal number of repre¬

sentatives to the duma. The executive is in the hands of

an elective mayor and an uprava which consists of several

members elected by the duma. Both are, in fact, function¬

aries under the governor, and the municipal institutions

have no real independent life.1

The organs of the central government in the provinces

are the uryadniks (a kind of gardes-champetres) in the

villages, the stanovoys and ispravniks (chiefs of the police)

in the districts, and the governors (a kind of Napoleonic

prefect) in each government—all invested, the tiryadniks

bee qolovatchoff TVre Years of Reforms in Russia-, The Finances of the

zmstoos (official publication); Dityatin, Municipal Self-Government in Russia,

2 vols., and very numerous and valuable papers in the reviews Vyestnik Evropy.

Otetchestvennyya Zapt ski, Russkaya Mysl, &c.

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > Encyclopaedia Britannica > Volume 21, ROT-Siam > (80) Page 70 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193628319 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.17 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|