New volumes of the Encyclopædia Britannica > Volume 30, K-MOR

(580) Page 546

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

546

MARRIAGE.

I. United Kingdom and European Countries.

SIXCE 1883, when the earlier volume of this En¬

cyclopedia (ninth edition) containing the article on

marriage was published, few subjects have been more

discussed and few branches of the law have

General -undergone such significant changes. From that

progress. year ^self dates the coming into operation of

the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, the great

charter which now regulates the position of married

women in England in regard to their property and their

contractual capacity generally. It was the outcome of a

long struggle which led first to the Act of 1870, a tenta¬

tive enactment passed to secure married women’s earnings

against appropriation by the husband, and in 1874 to an

amending Act for the protection of the husband against

debts of his wdfe contracted prior to the marriage, and

ultimately, in 1882, to the complete emancipation of the

wife’s property from marital control (see more fully below).

In the course of ten years English legislation in the

matter of married women’s property progressed from

perhaps the most backward to the foremost place in

Europe. By a curious contrast, the only two other

European countries where, in the absence of a settlement

to the contrary, independence of the wife’s property is

recognized, are Russia and Italy (Italian Civil Code, Art.

1425 et seq.).

Among other countries, in France a law of 1881 em¬

powered the married woman to open a deposit account

at the Post Office Savings Banks, but inasmuch as the

husband can lodge a caveat to prevent withdrawal of

the money, and can lay hands on the money as soon as

an application is made by the wife to take it out, the

protection is illusory. It must not, however, be supposed

that the position of married women in France in respect

of their property is abnormally hard. Their position is

only regulated from a different point of view, and in several

respects it is an exceptionally privileged one. It is mainly

owing to this that progress, in the sense of the recognition

of separate property, will probably be slower in France than

elsewhere. Thus, though by ante-nuptial marriage con¬

tract the paraphernal system of emancipation of the wife’s

property may be secured, it is seldom resorted to, because

in the absence of an ante-nuptial marriage contract—and

in France, as elsewhere, marriage contracts are uncommon

among the mass of the population—the wife is owner of

one - half of all property saved or personal property

acquired by succession or otherwise, after the marriage, by

either husband or wife. The husband during coverture

certainly has the absolute control of the whole of this

joint fortune, but on dissolution of the marriage the half

of it can be claimed by the wife or her heirs and assigns.

This system of community of property is engrained in

French institutions and custom as the common law of the

country, and there is no movement to follow the example

of Italy and adopt the paraphernal system as the common

law in its place. Among the French middle class the wife,

owing to her ownership of half the fortune acquired by

her husband, takes a more active part in his business life

and holds a higher business status generally than she

does in other countries. She is her husband’s partner in

all his enterprises, and has an equal interest with him in

all their proceeds. Sometimes wonder is expressed that

the bulk of French women seem so indifferent to agitation

for an increase of their independence, but isolated cases of

hardship are not considered a ground for altering a law on

which the whole social economy of the nation is based,

and which gives the French married woman a position in

her household and in her family surpassing in dignity

and prestige that of women in any other country.

In Scandinavia there is a marked tendency towards

contractual emancipation, but as yet it has not gone

farther than the married woman’s earnings. Sweden

adopted a law on this subject in 1874, Denmark

in 1880, Norway in 1888. Germany followed the

Civil Code which came into operation in 1900 (Art.

1367), providing that the wife’s wages or earnings shall

form part of her VorbeholUgut or separate property, which

a previous article (1365) placed beyond the husband’s

control. As regards property accruing to the wife in

Germany by succession, will, or gift inter vivos, it is

only separate property where the donor has deliberately

stipulated exclusion of the husband’s right.

In several other branches of the law of marriage the

United Kingdom is not as much to the front. This applies

to prohibition of marriage with a deceased wife’s sister (see

below), to breaches of promise of marriage, perhaps even

to the facility generally with which marriage is contracted

and the absence of specialized control through a civil

authority which might introduce more order and system

into the working of the chief social institution.1 Still

marriage holds its own, though severely criticized by

different contemporary writers, and the number of those

entering the state of matrimony does hot diminish, in

spite of warnings of its probable unhappiness. There is,

in fact, no significant change in the proportion of those

who marry to those who (acting on Mr Punch’s advice)

“don’t.” The following table shows that the tendency is

to increase rather than diminish :—

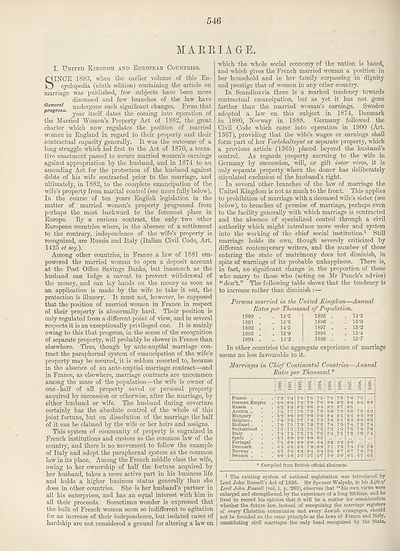

Persons married in the United Kingdom—Annual

Rates per Thousand of Population.

1890

1891

1892

1893

1894

14-5

14-6

14-5

13- 9

14- 2

1895

1896

1897

1898

1899

14- 3

15- 0

15-2

15-4

157

In other countries the aggregate experience of marriage

seems no less favourable to it.

Marriages in Chief Continental Countries—Annual

Rates per Thousand*

France .

German Empire

Russia .

Austria .

Hungary

Belgium.

Holland .

Switzerland

Italy

Spain

Portugal

Denmark

Norway .

Sweden .

7- 3 ;

l 8-0 I

8- 2

7- 5 I

8- 2 !

7'4 |

7-0 j

7- 1 !

I 7-4 '

8- 1 |

7-1 S

6-9

6-5 I

6-0 ;

7'5

1 7-9

I 9-4

! 7'9

9-3

' 7-5

; 7-2

7- 2

I 7-5

8- 1

6-4

i 6-4

I 5-7

7- 4

8- 0

9-2

80

8-4

7-8

7'4

7-2

7-4

6- 3

7- 1

6-5

5-9

5-9

7‘5

8'4

7- 8

8- 3

8-3

7-3

7-8

7-0

* Compiled from British official abstracts.

1 The existing system of national registration was introduced by

Lord John Russell’s Act of 1836. Sir Spencer Walpole, in his Life of

Lord John Russell (vol. i. p. 260), observes that “his own views were

enlarged and strengthened by the experience of a long lifetime, and he

lived to record his opinion that it will be a matter for consideration

whether the future law, instead of recognizing the marriage registers

of every Christian communion and every Jewish synagogue, should

not be founded on the same principle as the laws of France and Italy,

constituting civil marriages the only bond recognized by the State,-

MARRIAGE.

I. United Kingdom and European Countries.

SIXCE 1883, when the earlier volume of this En¬

cyclopedia (ninth edition) containing the article on

marriage was published, few subjects have been more

discussed and few branches of the law have

General -undergone such significant changes. From that

progress. year ^self dates the coming into operation of

the Married Women’s Property Act of 1882, the great

charter which now regulates the position of married

women in England in regard to their property and their

contractual capacity generally. It was the outcome of a

long struggle which led first to the Act of 1870, a tenta¬

tive enactment passed to secure married women’s earnings

against appropriation by the husband, and in 1874 to an

amending Act for the protection of the husband against

debts of his wdfe contracted prior to the marriage, and

ultimately, in 1882, to the complete emancipation of the

wife’s property from marital control (see more fully below).

In the course of ten years English legislation in the

matter of married women’s property progressed from

perhaps the most backward to the foremost place in

Europe. By a curious contrast, the only two other

European countries where, in the absence of a settlement

to the contrary, independence of the wife’s property is

recognized, are Russia and Italy (Italian Civil Code, Art.

1425 et seq.).

Among other countries, in France a law of 1881 em¬

powered the married woman to open a deposit account

at the Post Office Savings Banks, but inasmuch as the

husband can lodge a caveat to prevent withdrawal of

the money, and can lay hands on the money as soon as

an application is made by the wife to take it out, the

protection is illusory. It must not, however, be supposed

that the position of married women in France in respect

of their property is abnormally hard. Their position is

only regulated from a different point of view, and in several

respects it is an exceptionally privileged one. It is mainly

owing to this that progress, in the sense of the recognition

of separate property, will probably be slower in France than

elsewhere. Thus, though by ante-nuptial marriage con¬

tract the paraphernal system of emancipation of the wife’s

property may be secured, it is seldom resorted to, because

in the absence of an ante-nuptial marriage contract—and

in France, as elsewhere, marriage contracts are uncommon

among the mass of the population—the wife is owner of

one - half of all property saved or personal property

acquired by succession or otherwise, after the marriage, by

either husband or wife. The husband during coverture

certainly has the absolute control of the whole of this

joint fortune, but on dissolution of the marriage the half

of it can be claimed by the wife or her heirs and assigns.

This system of community of property is engrained in

French institutions and custom as the common law of the

country, and there is no movement to follow the example

of Italy and adopt the paraphernal system as the common

law in its place. Among the French middle class the wife,

owing to her ownership of half the fortune acquired by

her husband, takes a more active part in his business life

and holds a higher business status generally than she

does in other countries. She is her husband’s partner in

all his enterprises, and has an equal interest with him in

all their proceeds. Sometimes wonder is expressed that

the bulk of French women seem so indifferent to agitation

for an increase of their independence, but isolated cases of

hardship are not considered a ground for altering a law on

which the whole social economy of the nation is based,

and which gives the French married woman a position in

her household and in her family surpassing in dignity

and prestige that of women in any other country.

In Scandinavia there is a marked tendency towards

contractual emancipation, but as yet it has not gone

farther than the married woman’s earnings. Sweden

adopted a law on this subject in 1874, Denmark

in 1880, Norway in 1888. Germany followed the

Civil Code which came into operation in 1900 (Art.

1367), providing that the wife’s wages or earnings shall

form part of her VorbeholUgut or separate property, which

a previous article (1365) placed beyond the husband’s

control. As regards property accruing to the wife in

Germany by succession, will, or gift inter vivos, it is

only separate property where the donor has deliberately

stipulated exclusion of the husband’s right.

In several other branches of the law of marriage the

United Kingdom is not as much to the front. This applies

to prohibition of marriage with a deceased wife’s sister (see

below), to breaches of promise of marriage, perhaps even

to the facility generally with which marriage is contracted

and the absence of specialized control through a civil

authority which might introduce more order and system

into the working of the chief social institution.1 Still

marriage holds its own, though severely criticized by

different contemporary writers, and the number of those

entering the state of matrimony does hot diminish, in

spite of warnings of its probable unhappiness. There is,

in fact, no significant change in the proportion of those

who marry to those who (acting on Mr Punch’s advice)

“don’t.” The following table shows that the tendency is

to increase rather than diminish :—

Persons married in the United Kingdom—Annual

Rates per Thousand of Population.

1890

1891

1892

1893

1894

14-5

14-6

14-5

13- 9

14- 2

1895

1896

1897

1898

1899

14- 3

15- 0

15-2

15-4

157

In other countries the aggregate experience of marriage

seems no less favourable to it.

Marriages in Chief Continental Countries—Annual

Rates per Thousand*

France .

German Empire

Russia .

Austria .

Hungary

Belgium.

Holland .

Switzerland

Italy

Spain

Portugal

Denmark

Norway .

Sweden .

7- 3 ;

l 8-0 I

8- 2

7- 5 I

8- 2 !

7'4 |

7-0 j

7- 1 !

I 7-4 '

8- 1 |

7-1 S

6-9

6-5 I

6-0 ;

7'5

1 7-9

I 9-4

! 7'9

9-3

' 7-5

; 7-2

7- 2

I 7-5

8- 1

6-4

i 6-4

I 5-7

7- 4

8- 0

9-2

80

8-4

7-8

7'4

7-2

7-4

6- 3

7- 1

6-5

5-9

5-9

7‘5

8'4

7- 8

8- 3

8-3

7-3

7-8

7-0

* Compiled from British official abstracts.

1 The existing system of national registration was introduced by

Lord John Russell’s Act of 1836. Sir Spencer Walpole, in his Life of

Lord John Russell (vol. i. p. 260), observes that “his own views were

enlarged and strengthened by the experience of a long lifetime, and he

lived to record his opinion that it will be a matter for consideration

whether the future law, instead of recognizing the marriage registers

of every Christian communion and every Jewish synagogue, should

not be founded on the same principle as the laws of France and Italy,

constituting civil marriages the only bond recognized by the State,-

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > New volumes of the Encyclopædia Britannica > Volume 30, K-MOR > (580) Page 546 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193575041 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.18 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|