New volumes of the Encyclopædia Britannica > Volume 30, K-MOR

(368) Page 338

Download files

Complete book:

Individual page:

Thumbnail gallery: Grid view | List view

338

LOGIC

gained by a process of logical treatment of this experi¬

ence ”; as if our belief in causality could be neither a

'posteriori nor a priori, and beyond experience wake up

in a hypothetical major premiss of induction. Really, we

first experience that particular causes have particular effects;

then induce that causes similar to those have effects

similar to these; finally, deduce that when a particular

cause of the kind occurs it has a particular effect of the

kind by synthetic deduction, and that when a particular

effect of the kind occurs it has a particular cause of the

kind by analytic deduction with a convertible premiss,

as when Newton from planetary motions, like terrestrial

motions, analytically deduced a centripetal force to the

sun like centripetal forces to the earth. Moreover, causal

induction is itself both synthetic and analytic : according

as experiment combines elements into a compound, or

resolves a compound into elements, it is the origin of a

synthetic or an analytic generalization. Not, however,

that all induction is causal; but where it is not, there is

still less reason for making it a deduction from hypothesis.

When from the fact that the many crows in our experience

are black, we induce the probability that all crows whatever

are black, the belief in the particulars is quite independent

of this universal. How then can this universal be called,

as Sigwart, for example, calls it, the ground from which

these particulars follow ? I do not believe that the crows

I have seen are black because all crows are black, but vice

versd. Sigwart simply inverts the order of our knowledge.

In all induction, as Aristotle said, the particulars are the

evidence, or ground of our knowledge (principiwn cogno-

scendi), of the universal. In causal induction, the particu¬

lars contain the cause, or ground of the being (principium

essendi), of the effect, as well as the ground of our

inducing the law. In all induction the universal is the

conclusion, in none a major premiss, and in none the

ground of either the being or the knowing of the particulars.

Induction is simply generalization. It is not syllogism

in the form of Aristotle’s or Wundt’s inductive syllogism,

because, though starting only from some particulars, it

concludes with a universal; it is not syllogism in the

form called inverse deduction by Jevons, reduction by

Sigwart, inductive method by Wundt, because it often

uses particular facts of causation to infer universal laws

of causation; it is not syllogism in the form of Mill’s

syllogism from a belief in uniformity of nature, because

few men have believed in uniformity, but all have induced

from particulars to universals. Bacon alone was right

in altogether opposing induction to syllogism, and in

finding inductive rules for the inductive process from

particular instances of presence, absence in similar circum¬

stances, and comparison. But how from some particulars

of experience do we infer all universally 1 The answer to

this question is still a desideratum of logic.

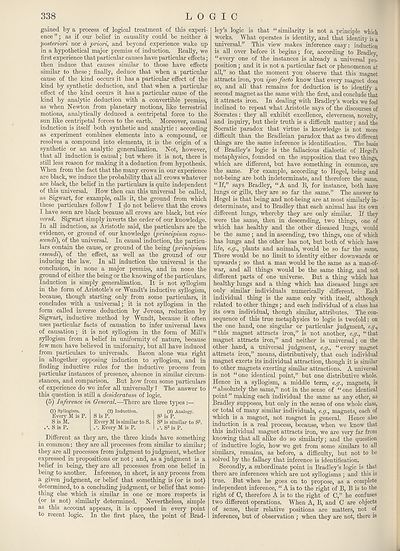

(5) Inference in General.—There are three types :—

(1) Syllogism.

Every M is P.

S is M.

Sis P.

(2) Induction.

Sis P.

Every M is similar to

. \ Every M is P.

(3) Analogy.

51 is P.

52 is similar to S1.

S2 is P.

Different as they are, the three kinds have something

in common: they are all processes from similar to similar;

they are all processes from judgment to judgment, whether

expressed in propositions or not; and, as a judgment is a

belief in being, they are all processes from one belief in

being to another. Inference, in short, is any process from

a given judgment, or belief that something is (or is not)

determined, to a concluding judgment, or belief that some¬

thing else which is similar in one or more respects is

(or is. not) similarly determined. Nevertheless, simple

as this account appears, it is opposed in every point

to recent logic. In the first place, the point of Brad¬

ley’s logic is that “similarity is not a principle which

works. What operates is identity, and that identity is a

universal.” This view makes inference easy: induction

is all over before it begins; for, according to Bradley,

“every one of the instances is already a universal pro¬

position ; and it is not a particular fact or phenomenon at

all,” so that the moment you observe that this magnet

attracts iron, you ipso facto know that every magnet does

so, and all that remains for deduction is to identify a

second magnet as the same with the first, and conclude that

it attracts iron. In dealing with Bradley’s works we feel

inclined to repeat what Aristotle says of the discourses of

Socrates: they all exhibit excellence, cleverness, novelty,

and inquiry, but their truth is a difficult matter; and the

Socratic paradox that virtue is knowledge is not more

difficult than the Bradleian paradox that as two different

things are the same inference is identification. The basis

of Bradley’s logic is the fallacious dialectic of Hegel’s

metaphysics, founded on the supposition that two things,

which are different, but have something in common, are

the same. For example, according to Hegel, being and

not-being are both indeterminate, and therefore the same.

“If,” says Bradley, “A and B, for instance, both have

lungs or gills, they are so far the same.” The answer to

Hegel is that being and not-being are at most similarly in¬

determinate, and to Bradley that each animal has its own

different lungs, whereby they are only similar. If they

were the same, then in descending, two things, one of

which has healthy and the other diseased lungs, would

be the same; and in ascending, two things, one of which

has lungs and the other has not, but both of which have

life, e.g., plants and animals, would be so far the same.

There would be no limit to identity either downwards or

upwards; so that a man would be the same as a man-of-

war, and all things would be the same thing, and not

different parts of one universe. But a thing which has

healthy lungs and a thing which has diseased lungs are

only similar individuals numerically different. Each

individual thing is the same only with itself, although

related to other things; and each individual of a class has

its own individual, though similar, attributes. The con¬

sequence of this true metaphysics to logic is twofold: on

the one hand, one singular or particular judgment, e.g.,

“this magnet attracts iron,” is not another, e.g., “that

magnet attracts iron,” and neither is universal; on the

other hand, a universal judgment, e.g., “ every magnet

attracts iron,” means, distributively, that each individual

magnet exerts its individual attraction, though it is similar

to other magnets exerting similar attractions. A universal

is not “one identical point,” but one distributive whole.

Hence in a syllogism, a middle term, e.g., magnets, is

“ absolutely the same,” not in the sense of “ one identical

point ” making each individual the same as any other, as

Bradley supposes, but only in the sense of one whole class,

or total of many similar individuals, e.g., magnets, each of

which is a magnet, not magnet in general. Hence also

induction is a real process, because, when we know that

this individual magnet attracts iron, we are very far from

knowing that all alike do so similarly; and the question

of inductive logic, how we get from some similars to all

similars, remains, as before, a difficulty, but not to be

solved by the fallacy that inference is identification.

Secondly, a subordinate point in Bradley’s logic is that

there are inferences which are not syllogisms ; and this is

true. But when he goes on to propose, as a complete

independent inference, “ A is to the right of B, B is to the

right of C, therefore A is to the right of C,” he confuses

two different operations. When A, B, and C are objects

of sense, their relative positions are matters, not of

inference, but of observation ; when they are not, there is

LOGIC

gained by a process of logical treatment of this experi¬

ence ”; as if our belief in causality could be neither a

'posteriori nor a priori, and beyond experience wake up

in a hypothetical major premiss of induction. Really, we

first experience that particular causes have particular effects;

then induce that causes similar to those have effects

similar to these; finally, deduce that when a particular

cause of the kind occurs it has a particular effect of the

kind by synthetic deduction, and that when a particular

effect of the kind occurs it has a particular cause of the

kind by analytic deduction with a convertible premiss,

as when Newton from planetary motions, like terrestrial

motions, analytically deduced a centripetal force to the

sun like centripetal forces to the earth. Moreover, causal

induction is itself both synthetic and analytic : according

as experiment combines elements into a compound, or

resolves a compound into elements, it is the origin of a

synthetic or an analytic generalization. Not, however,

that all induction is causal; but where it is not, there is

still less reason for making it a deduction from hypothesis.

When from the fact that the many crows in our experience

are black, we induce the probability that all crows whatever

are black, the belief in the particulars is quite independent

of this universal. How then can this universal be called,

as Sigwart, for example, calls it, the ground from which

these particulars follow ? I do not believe that the crows

I have seen are black because all crows are black, but vice

versd. Sigwart simply inverts the order of our knowledge.

In all induction, as Aristotle said, the particulars are the

evidence, or ground of our knowledge (principiwn cogno-

scendi), of the universal. In causal induction, the particu¬

lars contain the cause, or ground of the being (principium

essendi), of the effect, as well as the ground of our

inducing the law. In all induction the universal is the

conclusion, in none a major premiss, and in none the

ground of either the being or the knowing of the particulars.

Induction is simply generalization. It is not syllogism

in the form of Aristotle’s or Wundt’s inductive syllogism,

because, though starting only from some particulars, it

concludes with a universal; it is not syllogism in the

form called inverse deduction by Jevons, reduction by

Sigwart, inductive method by Wundt, because it often

uses particular facts of causation to infer universal laws

of causation; it is not syllogism in the form of Mill’s

syllogism from a belief in uniformity of nature, because

few men have believed in uniformity, but all have induced

from particulars to universals. Bacon alone was right

in altogether opposing induction to syllogism, and in

finding inductive rules for the inductive process from

particular instances of presence, absence in similar circum¬

stances, and comparison. But how from some particulars

of experience do we infer all universally 1 The answer to

this question is still a desideratum of logic.

(5) Inference in General.—There are three types :—

(1) Syllogism.

Every M is P.

S is M.

Sis P.

(2) Induction.

Sis P.

Every M is similar to

. \ Every M is P.

(3) Analogy.

51 is P.

52 is similar to S1.

S2 is P.

Different as they are, the three kinds have something

in common: they are all processes from similar to similar;

they are all processes from judgment to judgment, whether

expressed in propositions or not; and, as a judgment is a

belief in being, they are all processes from one belief in

being to another. Inference, in short, is any process from

a given judgment, or belief that something is (or is not)

determined, to a concluding judgment, or belief that some¬

thing else which is similar in one or more respects is

(or is. not) similarly determined. Nevertheless, simple

as this account appears, it is opposed in every point

to recent logic. In the first place, the point of Brad¬

ley’s logic is that “similarity is not a principle which

works. What operates is identity, and that identity is a

universal.” This view makes inference easy: induction

is all over before it begins; for, according to Bradley,

“every one of the instances is already a universal pro¬

position ; and it is not a particular fact or phenomenon at

all,” so that the moment you observe that this magnet

attracts iron, you ipso facto know that every magnet does

so, and all that remains for deduction is to identify a

second magnet as the same with the first, and conclude that

it attracts iron. In dealing with Bradley’s works we feel

inclined to repeat what Aristotle says of the discourses of

Socrates: they all exhibit excellence, cleverness, novelty,

and inquiry, but their truth is a difficult matter; and the

Socratic paradox that virtue is knowledge is not more

difficult than the Bradleian paradox that as two different

things are the same inference is identification. The basis

of Bradley’s logic is the fallacious dialectic of Hegel’s

metaphysics, founded on the supposition that two things,

which are different, but have something in common, are

the same. For example, according to Hegel, being and

not-being are both indeterminate, and therefore the same.

“If,” says Bradley, “A and B, for instance, both have

lungs or gills, they are so far the same.” The answer to

Hegel is that being and not-being are at most similarly in¬

determinate, and to Bradley that each animal has its own

different lungs, whereby they are only similar. If they

were the same, then in descending, two things, one of

which has healthy and the other diseased lungs, would

be the same; and in ascending, two things, one of which

has lungs and the other has not, but both of which have

life, e.g., plants and animals, would be so far the same.

There would be no limit to identity either downwards or

upwards; so that a man would be the same as a man-of-

war, and all things would be the same thing, and not

different parts of one universe. But a thing which has

healthy lungs and a thing which has diseased lungs are

only similar individuals numerically different. Each

individual thing is the same only with itself, although

related to other things; and each individual of a class has

its own individual, though similar, attributes. The con¬

sequence of this true metaphysics to logic is twofold: on

the one hand, one singular or particular judgment, e.g.,

“this magnet attracts iron,” is not another, e.g., “that

magnet attracts iron,” and neither is universal; on the

other hand, a universal judgment, e.g., “ every magnet

attracts iron,” means, distributively, that each individual

magnet exerts its individual attraction, though it is similar

to other magnets exerting similar attractions. A universal

is not “one identical point,” but one distributive whole.

Hence in a syllogism, a middle term, e.g., magnets, is

“ absolutely the same,” not in the sense of “ one identical

point ” making each individual the same as any other, as

Bradley supposes, but only in the sense of one whole class,

or total of many similar individuals, e.g., magnets, each of

which is a magnet, not magnet in general. Hence also

induction is a real process, because, when we know that

this individual magnet attracts iron, we are very far from

knowing that all alike do so similarly; and the question

of inductive logic, how we get from some similars to all

similars, remains, as before, a difficulty, but not to be

solved by the fallacy that inference is identification.

Secondly, a subordinate point in Bradley’s logic is that

there are inferences which are not syllogisms ; and this is

true. But when he goes on to propose, as a complete

independent inference, “ A is to the right of B, B is to the

right of C, therefore A is to the right of C,” he confuses

two different operations. When A, B, and C are objects

of sense, their relative positions are matters, not of

inference, but of observation ; when they are not, there is

Set display mode to:

![]() Universal Viewer |

Universal Viewer | ![]() Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Mirador |

Large image | Transcription

Images and transcriptions on this page, including medium image downloads, may be used under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence unless otherwise stated. ![]()

| Encyclopaedia Britannica > New volumes of the Encyclopædia Britannica > Volume 30, K-MOR > (368) Page 338 |

|---|

| Permanent URL | https://digital.nls.uk/193572285 |

|---|

| Attribution and copyright: |

|

|---|---|

| Shelfmark | EB.18 |

|---|---|

| Description | Ten editions of 'Encyclopaedia Britannica', issued from 1768-1903, in 231 volumes. Originally issued in 100 weekly parts (3 volumes) between 1768 and 1771 by publishers: Colin Macfarquhar and Andrew Bell (Edinburgh); editor: William Smellie: engraver: Andrew Bell. Expanded editions in the 19th century featured more volumes and contributions from leading experts in their fields. Managed and published in Edinburgh up to the 9th edition (25 volumes, from 1875-1889); the 10th edition (1902-1903) re-issued the 9th edition, with 11 supplementary volumes. |

|---|---|

| Additional NLS resources: |

|